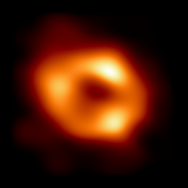

One of the bright spots in the dark years of the 2020s was, paradoxically, the pictures of black holes—the first direct visual evidence for the astronomical phenomenon.

Taken by astronomers with the Event Horizon Telescope, the image splashed across the front pages of newspapers around the world. The 2019 picture captured a black hole in a galaxy millions of light-years away from us; but in 2022, they have announced the first image of the supermassive black hole that squats at the center of our own galaxy.

Named Sagittarius A*, this black hole is no threat to us Earthlings. But it could help us understand how the Milky Way formed, as well as the strange physics that happen in and near black holes.

“The galactic center black hole is special for us,” said John Carlstrom, the Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Distinguished Service Professor of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Physics at the University of Chicago. “In a sense, it's our own black hole. We'd really like to know and understand what's going on there, and to be able to tie it to the dynamics of our galaxy as a whole.”

A telescope the size of the Earth

Black holes are so named because they themselves cannot be seen—they are regions of space where gravity is so powerful that not even light can escape. The bright “donuts” of light in the famous images are actually light and matter being ripped apart and chewed up by the black holes.

But these black holes are so far away that even such hazy images marked an incredible feat of science, engineering and global collaboration.

Scientists figured out that if they pointed telescopes all around the Earth at the same spot at the same time, and cross-referenced the data, it could act as though it was one big telescope covering the size of the Earth. This is what the “Event Horizon Telescope” really is—a collection of telescopes around the world that are normally used for other purposes.

Carlstrom is the director of one such facility, the South Pole Telescope, which sits in Antarctica. It was built to survey the sky for remnants of the light left over from the Big Bang. But its remote location, chosen because of the extraordinarily clear skies and low humidity, also makes it perfect to moonlight as part of the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration.

The South Pole Telescope already served as an important linchpin for taking the first image of a black hole, but its geographic position makes it even more crucial for observing Sagittarius A*.

“The South Pole Telescope is sitting there at the bottom of the Earth, and that means we can look at the center of our galaxy all the time, 24 hours a day,” said Carlstrom.

What could Sagittarius A* tell us?

Black holes have always fascinated scientists. “They're these incredibly radical objects. I mean, they're made out of space and time!” said UChicago Prof. Daniel Holz, an expert on black holes. And as such, they offer a unique opportunity to understand the laws of the universe.

In the last decade or two, we’ve learned a lot more about black holes: Scientists such as Nobel laureate Andrea Ghez helped prove the very existence of Sagittarius A*, and the LIGO detectors picked up the ripples from two black holes colliding in a faraway galaxy.

Still, there’s a lot more left to discover. For example, Holz said, many revolve around the stuff that falls into black holes.

“We have tons of questions. What falls in? How often does it fall in? When it falls in, how much gets spit back out? Does it end up causing the black hole to spin, and how does all of that affect the galaxy around it?” he said.

Another one: What role do these black holes at the centers of galaxies play in how we came to be here?

Scientists now think that there are supermassive black holes squatting at the centers of most large galaxies, like spiders in the middle of their intricate webs. Many believe that these black holes are involved in how galaxies form in the first place, because the size of each black hole is correlated with the size of its respective galaxy.

“If you have a big galaxy, you have a big black hole at the center, and if you have a small galaxy you have a small black hole at the center—and we don't know why that would be,” said Holz. “We feel like there must be something profound there, if we could only uncover how these things are tied together.”

In fact, scientists are not sure how these supermassive black holes actually form in the first place. We have a solid theory to explain how smaller black holes are made—by a certain type of star going supernova and collapsing in on itself. But the larger ones are a mystery. We know black holes can collide and form bigger black holes, because that’s what we saw with LIGO. But we don’t know if that’s how these supermassive black holes formed, or whether they simply ate a lot of nearby stars, or something else that no one has thought of yet.

Getting more data, with the Event Horizon Telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, LIGO, and other facilities, is the only way to shed light on these mysterious objects.

‘It gets much trickier’

If a black hole lurks at the center of our own galaxy, why did the first picture show us one that was much further away? It turns out that Sagittarius A* is elusive for multiple reasons.

The first picture we took was of M87, which is much, much larger than Sagittarius A*, and that makes a difference.

“Sagittarius A* is a thousand times smaller than M87—still a monster, but a thousand times smaller—and as a consequence it's actually evolving a thousand times faster,” explained Prof. John Carlstrom.

“M87 changed subtly on timescales of days; now with Sagittarius A*, it’s changing in timescales of minutes, so it gets much trickier. We have to adapt the analysis to take into account that it's changing so quickly,” he said.

Imagine trying to take a picture of someone riding past on a bike. If they’re pedaling slowly, it’s easier to get a crisp photo. But the faster they’re moving, the blurrier the photo tends to be.

The SgrA* black hole was changing rapidly as it was observed, so the EHT collaboration created thousands of possible interpretations from the data and averaged them together to create one representative image. Animation by Caltech/IPAC.

Another challenge is to account for dust and gas in our own galaxy that can cloud the picture.

Finally, to astrophysicists, Sagittarius A* is somewhat of a “boring” black hole. That is, things don’t fall into it that often. The more a black hole eats, the more interesting it is to observe, because all we get to see are the crumbs from its meals. (Scientists also think Sagittarius A* may eat less than its counterparts in other galaxies, an oddity that could itself have interesting implications.)

The entire journey has been fascinating, said Carlstrom. He was impressed by the collaboration and technique needed to combine the data from telescopes around the world.

“It’s wild. I mean, the resolution is like looking across from New York to read the date on a dime on the Golden Gate Bridge,” he said. “Seeing those images for the first time was just fantastic.”