An exoplanet is what we call planets that exist outside of our own solar system. The first one was discovered in 1992, but as we get more powerful and precise telescopes and instruments, scientists have been discovering more and more of these faraway planets—more than 6,000 so far. But scientists think there are trillions more out there in the universe. If you look up at the night sky, it’s likely that most of the stars you see have planets around them.

These planets are very far away and hard to see, so scientists have to tease out tiny clues about them, but there appear to be all kinds of planets—big, small, hot, icy, rocky, gaseous.

So far, we haven’t found any definitive signs of life. But we are learning more all the time.

What is an exoplanet?

Humans have wondered for millennia if we are alone in the universe.

For a long time, humans only knew about the planets in our own solar system—the eight you learned in school. But thanks to more powerful telescopes and instruments, we now definitively know that this is just the tiniest tip of the iceberg.

The first confirmed exoplanet was found in 1992, but there was an explosion of discoveries in the mid-2000s. NASA’s Exoplanet Catalog now has more than 6,000 entries. Based on the frequency with which we see exoplanets in our own “cosmic neighborhood,” it’s likely that there are trillions more out there in the universe.

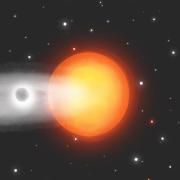

Exoplanets are mostly far too small to be seen directly with telescopes, but scientists have come up with innovative ways to find them nonetheless—such as looking for the dip in the light of a star when a planet crosses in front of it.

Thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope, the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, we are making huge new leaps in finding out more about what these planets look like. We do know that they come in all shapes, sizes and compositions.

“The amount of information we have gotten about exoplanets just in the last 10 years is incredible,” said UChicago Prof. Jacob Bean. “We’re writing whole new chapters on exoplanets all the time.”

Thus far there’s no definite detection of life, but the search is ongoing.

How many exoplanets are there?

So far, we’ve catalogued about 6,000 exoplanets. (NASA’s live tracker is here.) But based on how frequently we’ve found them, scientists think there are probably at least a trillion more out there in our galaxy alone.

“If you look up at the night sky, most—if not all—of the stars you see have planets around them,” said UChicago Assoc. Prof. Leslie Rogers.

Is there life on other planets?

We don’t yet know if there is life on other planets. Astrophysicists are just as excited as you are about the possibility, and it’s an active area of research; but so far, we haven’t found any definitive signs of life.

When evaluating possible planets out of the thousands out there, explained Prof. Bean, scientists look for liquid water as a main guiding principle.

“All life on Earth needs liquid water, no matter how different it looks; that’s one of the unifying principles of all life here,” he said. “It’s also a good way to narrow down planet candidates, because liquid water implies the planet must be the just-right distance from its star to be warm but not boiling.”

To keep a planet in this ‘Goldilocks zone,’ it’s helpful to have an atmosphere like Earth does—it’s one of the reasons Earth has stayed consistently habitable for billions of years. You also want a nice, stable star like our sun; many of the planets we’ve seen out there are periodically blasted by flare-ups from their home stars.

Most of the planets discovered so far aren’t particularly habitable, especially for humans. They often have surfaces existing at thousands of degrees, atmospheres with poisonous gases, or no atmospheres at all.

That said, most astronomers think the odds of life elsewhere in the universe are extremely high. (It might just be single-celled life, but it would be life.)

When was the first exoplanet discovered?

The first confirmed exoplanet discovered was found in 1992, by a pair of astronomers observing a star called a pulsar. Like the name suggests, pulsars send off very regular “pulses” of radio waves. But the readings from this star, PSR B1 257+12, were a little odd. After intense analysis, Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail concluded that the star had a pair of planets that were causing it to “wobble” slightly, which was reflected in the radio wave pulses.

Then, in 1995, scientists were able to catch the change in light from a regular star as a large planet circled around it. This planet, known as 51 Pegasi b, made many headlines and is often considered to have kicked off the modern era of exoplanet discovery; the technique that was used is still one of the most common approaches.

What do exoplanets look like?

It’s really, really hard to directly see an exoplanet with a telescope—they are so faint and far away that the best we’ve managed is essentially just a single pixel, for a handful of planets.

That means that most of what we know about these planets is by indirect measures, such as looking at the planet’s effects on their much larger stars. It’s a bit like working out the shape of an object by the shadows it casts. (All of the pictures you’ve seen of planet surfaces are artist’s guesses). But we can get a surprising amount of information from these methods.

Today, we know that there are all kinds of planets out there. Most are much bigger than Earth, some smaller. Some are partly covered in lava. Some are likely covered in ice or have vast subterranean oceans. Some are entirely gas, like Jupiter. Some have two suns (yes, like Tatooine). Some are “tidally locked,” meaning one side of the planet always faces the sun and the other is in perpetual night. Other worlds have clouds and winds and sister planets, as we do. Some have atmospheres—made up of hydrogen, methane, or other molecules—though we haven’t yet found an “Earth twin” that looks exactly like ours does.

Scientists subdivide the planets into a few categories:

- Gas giants. These are similar to Saturn or Jupiter, but they can be much larger. Because many of them orbit very close to their stars and are extremely hot, they were some of the first to be spotted.

- Terrestrial planets. Like Earth, these planets are mostly made up of rock and metal. Some may have oceans and atmospheres, too, though we haven’t yet found any that we think are “Earth twins.”

- Neptune-like planets. These are rocky planets around the size of Neptune, with hydrogen or helium-dominated atmospheres.

- “Mini-Neptunes.” For some reason, there seem to be a very large number of planets that are larger than Earth, but smaller than Neptune. They are made of some mixture of rock, gas and water. They are the only type that has no equivalent in our own solar system.

How do we find exoplanets?

Most exoplanets are too far away and faint to be seen directly, so scientists have come up with creative ways to find and study them indirectly.

The two most successful methods so far are:

- Seeing a telltale “wobble” from a star. The presence of planets makes a star wobble a little. By using telescopes and instruments to very precisely measure the light coming from a star, scientists can detect these tiny wobbles as the star moves towards us and away. Known as the radial velocity method, this is one of the most widely used approaches. It can tell you the number of planets around a star and even the masses of each of those planets.

- Looking for the shadow of a planet passing in front of a star. As planets orbit around their stars, they periodically block out a bit of light coming from the star. If your telescope is sensitive enough to pick up on this change—and the planet’s orbit happens to align so that it crosses in front of the star from our viewpoint—you can find planets this way. It can tell you how many planets there are and the diameters of those planets (by how much light they block). It’s known as the transit method.

We can also look for the tiny amount of starlight that is filtered through a planet’s atmosphere, and see which wavelengths of light are blocked. This technique, known as spectroscopy, can tell us which atoms are in the atmosphere.

Other methods include:

- Looking for a flash of light from a cosmic ‘magnifying glass.’ As light travels across the universe, it can get bent by the gravity of large objects. Sometimes, light from a more distant star will get bent and magnified by the gravity of stars and planets on its way to Earth, which we see as a very brief flash of light. This method, known as the microlensing method, is just beginning to be explored, but it’s the one with the furthest reach—it could detect planets that are thousands rather than just hundreds of light-years away.

- Looking directly at the planet itself. This is very difficult; these planets are so far away and their stars are so bright that it’s very hard to see them, like trying to stare at a floodlight and see the glow of a firefly next to it (on the other side of the country). But a handful of planets have been found this way—mostly gas giants that are hot enough to glow on their own.

- Catching a star wobbling in the sky. Another way to catch a star wobbling due to the presence of a planet is astrometry, which looks for the movement of stars as they move side-to-side or up-and-down from our perspective. This is very tricky to do and only a handful of planets have been found so far with this method; but astronomers are expecting many more to come as the European Space Agency’s recent GAIA mission releases its data.

These methods all tell you slightly different things about a planet, so to get a more complete picture, scientists usually combine multiple of them.

All of them depend on very powerful telescopes, often based in space, such as the Hubble Space Telescope and the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope. NASA has also launched several smaller missions specifically to study exoplanets, such as Kepler (launched in 2009), and TESS (launched in 2018).

Ground-based telescopes have also made many discoveries; for example, University of Chicago scientists built MAROON-X, an instrument attached to the Gemini Observatory in Hawaii that acts like a “radar gun” for stars to find exoplanets around them.

How do exoplanets form?

The question of how planets form is an enormously important question to direct the search for habitable worlds. Scientists want to know the conditions that create different types of planets, so that they can narrow down the search for stars and star systems that are likely to have these conditions.

Our current best theory is that planets are formed in the disk of dust swirling around stars. Over time, this dust clumps together into larger and larger pieces, which eventually form planets. This is what happened with Earth.

“From what we’ve seen, it looks like star and planet formation are intrinsically linked,” said Prof. Bean.

Scientists aren’t sure about the details, though. Do planets stay in the same orbits where they originally formed? Or do they migrate inward over time? And why are there such a wide variety of different kinds of planets?

Current and upcoming telescope and space missions, such as the European Space Agency’s GAIA mission, the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope, and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, will be able to tell us much more about these and other questions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the closest exoplanet to Earth?

The closest planets to Earth beyond our solar system are around a star named Proxima Centauri. We think at least three planets orbit this star, which is 4.2 light-years away. For now, they’re code-named Proxima b, c and d. It’d be tricky to live there, though—Proxima Centauri is prone to flareups that probably blast the planets with intense UV radiation.

Can I go there?

Unfortunately, there’s a long way to go before we have the technology to visit even the planets in our own solar system, let alone others. All of these exoplanets are many light-years away, meaning that even if you were traveling at the speed of light (much faster than any rocket we’ve ever managed to create) it would take years to centuries to get there.

Do exoplanets have moons?

Very likely! They’re called exomoons. But because they are even smaller and harder to see than exoplanets themselves, they’ve been difficult to find with certainty.

It’s unconfirmed, but exomoons may be orbiting the planets Kepler-1708 b and Kepler-1625 b, which are gas giants similar to Jupiter. These moons are huge, much larger than our moon or even Earth itself. Scientists expect many more to be discovered.

What is the biggest exoplanet?

The largest planets we’ve seen so far are gas giant planets, similar to Jupiter or Saturn in our solar system, except much bigger. For example, the planet HAT-P-67 b is twice the size of Jupiter (but much less dense).

What’s with the weird names?

Most exoplanets have official names consisting of the star name—which is often taken from the survey that discovered them—followed by a lowercase letter indicating the order it was found. So an exoplanet named Kepler-55 d, for example, orbits a star named Kepler-55 and was the third planet found in that star system. (The star itself counts as the “a”).

Are there any Earth-like exoplanets?

We have found many planets that are roughly the same size and makeup as Earth, but we don’t yet have proof that any of them have other Earth-like characteristics (for example, oceans and a nice thick breathable atmosphere).

A famous one is a set of seven planets orbiting a star called TRAPPIST-1. Because it’s relatively close to Earth, only 40 light-years away, we’ve been able to get good readings on the system. There are seven rocky planets, all in the “Goldilocks zone”—close enough to be warmed by the star, but not so close that they’re cooked by radiation. Scientists are closely studying these planets to see if any have atmospheres like Earth’s.

Can I help find exoplanets?

Yes! NASA has multiple citizen science programs where you can help the search by sifting through telescope images to look for planets. Multiple discoveries have already been made by citizens without scientific backgrounds!

Last reviewed December 2025.