Atop a dormant volcano in Hawaii, an extremely delicate instrument—designed to help scientists find distant worlds—is scattered across the floor in hundreds of pieces.

“Imagine trying to assemble one of those huge LEGO sets, except there’s no instruction book; you’ve done it once before, but then you had to take it all apart and put it in little bags,” said Jacob Bean, associate professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Chicago. “Also you’re at 14,000 feet, and when the air is that thin it impairs your judgment and thinking, and so here you are working 12-hour shifts lifting heavy things but also trying to put together a delicate instrument.”

This was Bean’s task as the head of a UChicago project to build and install an innovative instrument that will scan the skies for new exoplanets—worlds in other solar systems that could potentially host life. Over the past eight years, Bean and his team had designed and built the instrument, called MAROON-X; this summer they finally attached it to a telescope at the Gemini Observatory at the top of Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

“It has been a pretty intense six months for my team to commission this instrument,” said Bean, an expert in faraway worlds whose research focuses on discovering and examining potentially habitable planets in other solar systems. “But in the next 10 years we’re going to learn things about habitable worlds that we’d never known before. It’s going to be really transformative.”

Several decades ago, advances in technology allowed scientists to begin detecting the very faint signatures from planets orbiting other stars in faraway solar systems. There’s been an explosion of discoveries; currently, NASA lists 4,000 confirmed exoplanets and thousands more candidates.

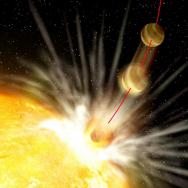

However, we still have no confirmed Earth-like exoplanets with habitable surface conditions. The thing about Earth-like planets, which is why it is taking so long to be able to find and characterize them, is that they’re extremely hard to see. Because these planets are circling around a star that is at least a million times brighter than they are, trying to look directly for them is like trying to see a lightning bug next to a lighthouse that is on the other side of the country. So scientists have to find indirect ways of finding them based on the effects they have on their stars.

MAROON-X does this by noticing the extremely tiny gravitational tug that an exoplanet (or two, or five, or seven) exerts on its star as it orbits around it. This tug causes the star to wobble just the slightest bit in its orbit. But that’s enough motion to catch it.

Attached to the Gemini North telescope, MAROON-X takes all the light gathered by the 25-foot telescope and focuses it down to a spot that is the width of a human hair. Then it separates out that light into the different colors of the rainbow and reads the intensity of each band. The color of the light will change slightly as the star moves forward or back. “It’s kind of like a radar gun for stars,” Bean said.

By catching this wobble, scientists can calculate the mass of the hidden planet (or planets) pulling on the star.

The precision needed for this, of course, is incredible. “When the light hits our detector, that shift is beyond imperceptible to the human eye. It’s a thousandth of a pixel. It’s approaching the size of the silicon atoms in the detector,” Bean said. “This is a star that is faint even for big telescopes. And we can tell if it’s moving towards or away from us at a rate comparable to human walking speed—that is, a few feet per second.”

“The changes that we’re looking for are so tiny that every night before we observe, we have to re-calibrate the instrument,” said research scientist Andreas Seifahrt, who built MAROON-X with Bean.

‘It’s really been a labor of love’

Bean and Seifahrt spent nearly a decade designing and building MAROON-X; it’s so precise that the environment needs to be exquisitely controlled. “Even a tiny change in temperature or air pressure will throw off the readings, so it’s built like a Russian nesting doll—it is inside a vacuum chamber that is itself insulated and inside a walk-in fridge that keeps the temperature stable to a thousandth of a degree,” Bean said.

Once they were satisfied with the instrument’s performance, then came the painstaking—and terrifying—work to transport it from Chicago to Hawaii. “Spending eight years on this instrument and then watching from the loading dock as the truck drives away with it and you won’t see it until two weeks later at the top of a mountain across an ocean—it’s pretty nerve-wracking,” Seifahrt said.

But the crates with the equipment made it safely to Hawaii, where Bean, Seifahrt, and postdocs Julian Stürmer and David Kasper got their LEGO set assembled. On September 23, MAROON-X took its official first-light readings.

The instrument will work in concert with NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) to get a full picture of candidate exoplanets. TESS looks for the dimming of the light as a planet crosses in front of a star, so scientists can find how big it is. By combining that with MAROON-X’s mass data, you can calculate an exoplanet’s density—which tells you if you’re looking at a rocky planet, like Earth, or a gaseous one, like Jupiter.

MAROON-X also will be able to detect signatures from the atmosphere of the planet, such as its composition and thickness.

“Long-term, we hope to be able to look for biosignatures—things that would only exist if life put them there,” Bean said. “For example, in Earth’s atmosphere, we only have oxygen because it was put there by plants. It’s a puzzle with a lot of different pieces.”

As they gather new data, Bean expects to work with UChicago colleagues including planetary composition experts Leslie Rogers, Dorian Abbott and Edwin Kite, and crack exoplanet hunter Daniel Fabrycky, to turn the readings into predictions about the faraway exoplanets. Soon, too, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will launch as the successor to Hubble, bringing even more imaging capabilities to bear on the question.

In addition to Bean, Seifahrt, Stürmer, and Kasper, multiple generations of UChicago undergraduate students, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers worked on MAROON-X. “It’s really been a labor of love for my team,” Bean said, “and now it’s finally real. It’s a very exciting time.”

Seifahrt agreed: “Pulling this off with such a small team and a limited budget is really an achievement. Looking back, it was kind of an insane thing to do—but we think it’s really going to be a trailblazing instrument.”

Funding: The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Gemini Observatory, and the University of Chicago