Most visible matter in the universe doesn’t look like our textbook picture of a nucleus surrounded by tethered electrons. Out beyond our borders, inside massive clusters, galaxies swim in a sea of plasma—a form of matter in which electrons and nuclei wander unmoored.

Though it makes up the majority of the visible matter in the universe, this plasma remains poorly understood; scientists do not have a theory that fully describes its behavior, especially at small scales.

However, a University of Chicago astrophysicist led a study that provides a brand-new glimpse of the small-scale physics of such plasma. Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, scientists took a detailed look at the plasma in a distant galaxy cluster and discovered the flow of plasma is much less viscous than expected and, therefore, turbulence occurs on relatively small scales—an important finding for our numerical models of the largest objects in the universe.

“High-resolution X-ray observations allowed us to learn some surprising truths about the viscosity of these plasmas,” said Irina Zhuravleva, an assistant professor of astrophysics and first author of the study, published June 17 in Nature Astronomy. “One might expect that variations in density that arise in the plasma are quickly erased by viscosity; however, we saw the opposite—the plasma finds ways to maintain them.”

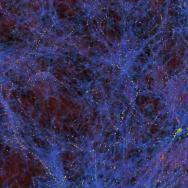

Scattered around the universe are massive clusters of galaxies, some of them millions of light-years across containing thousands of galaxies. They sit in a type of plasma that we cannot recreate on Earth. It is extremely sparse—on the order of a sextillion times less dense than air on Earth—and has very weak magnetic fields, tens of thousands of times weaker than we experience on the Earth’s surface. To study this plasma, therefore, scientists must rely on cosmic laboratories such as clusters of galaxies.

Zhuravleva and the team chose a relatively nearby galaxy cluster called the Coma Cluster, a gigantic, bright cluster made up of more than 1,000 galaxies. They chose a less dense region away from the cluster center, where they hoped to be able to capture the average distance that particles travel between interactions with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. In order to build a high-quality map of the plasma, they observed the Coma cluster for almost 12 days—much longer than a typical observing run.

One thing that jumped out was how viscous the plasma was—how easily it’s stirred. “One could expect to see the viscosity resisting chaotic motions of plasma as we zoom in to smaller and smaller scales,” Zhuravleva said. But that didn’t happen; the plasma was clearly turbulent even on such small scales.

“It turned out that plasma behavior is more similar to the swirling motions of milk stirred in a coffee mug than the smoother ones that honey makes,” she said.

Such low viscosity means that microscopic processes in plasma cause small irregularities in the magnetic field, causing particles to collide more frequently and making the plasma less viscous. Alternately, Zhuravleva said, viscosity could be different along and perpendicular to magnetic field lines.

Understanding the physics of such plasmas is essential for improving our models of how galaxies and galaxy clusters form and evolve with time.

“It is exciting that we were able to use observations of clusters of galaxies to understand fundamental properties of intergalactic plasmas,” said Zhuravleva. “Our observations confirm that clusters are great laboratories that can sharpen theoretical views on plasmas.”

Other scientists on the study were affiliated with Stanford University, the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany, the Space Research Institute in Russia, the University of Oxford, Niels Bohr International Academy, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Masaryk University, Eötvös Loránd University and Hiroshima University.

Citation: “Suppressed effective viscosity in the bulk intergalactic plasma.” Zhuravleva et al, Nature Astronomy, June 17, 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-019-0794-z

Funding: NASA, Russian Science Foundation, Simons Foundation, UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, UK Science and Technology Facilities Council, Hungarian Academy of Sciences.