In the fall of 2016, Carla D. Hayden had just been confirmed as the 14th librarian of Congress—the first woman and the first African American to hold the position. Hayden, AM’77, PhD’87, was wandering the stacks in the James Madison Memorial Building, familiarizing herself with the vast collections under her charge (at that time, more than 164 million items).

Books in hundreds of languages; the papers of Rosa Parks, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sigmund Freud, 23 presidents, and 36 Supreme Court justices; the world’s largest comic book collection. A lock of Walt Whitman’s hair, a map used by Lewis and Clark on their westward expedition, the palm print of Amelia Earhart.

As Hayden walked the aisles, taking it all in, she arrived at a set of boxes labeled “Frederick Douglass.” She got chills. Hayden reveres Douglass. His life, perhaps more than any other, testifies to the power of books and the life-giving force of literacy.

She quotes him often: “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” Hayden asked the curator serving as her guide if she could have a look. Of course, the curator said. Hayden pulled a random file from one of the boxes and marveled at what she had found.

She was holding the same paper that Douglass had held 151 years before, that had rested on his desk under his hand as he recorded some of his thoughts on the death of President Abraham Lincoln. She recalls seeing where Douglass had used the word “assassinated” and crossed it out. Then, darker, he had written the word “killed,” but that, too, he crossed out.

He next tested the word “murdered.” He must have thought that fitting, as it remained. This man’s thoughts and emotions leapt from the depths of history and touched Hayden. “When you see a piece of writing in the person’s own hand,” she says, “you can almost feel it, like electricity.”

A five-decade career in librarianship has made Hayden familiar with these “pinch-me moments.” She has experienced plenty herself and seen others quickened by the discovery of certain books or historical objects. Now at the helm of the world’s largest library, she wants to share these moments with everyone in the country.

“The effort to open up the institution and its collections to the general public has been at the heart of what Carla’s doing,” says David Ferriero, who, as head of the National Archives, worked closely with Hayden until his retirement in April 2022. Hayden has poured resources into digitization. She seeks to draw children and teenagers and people of color to a place that, historically, has expended little effort attracting or welcoming them.

She is trying, above all, to bring the library into people’s lives, highlighting its role as a keeper and shaper of America’s prismatic story.

To this end, Hayden joined Twitter her first day on the job. Posting as @LibnOfCongress, she uses the platform to turn the library inside out, to spread its wonders, and, like any clever user of social media, to get attention.

When classically trained flutist turned superstar Lizzo came through Washington for a Sept. 27 concert, Hayden tweeted an invitation for her to visit the library and view its flute collection (the world’s largest), and even play a few notes on James Madison’s crystal flute. Lizzo’s response came within a day: “IM COMING CARLA! AND IM PLAYIN THAT CRYSTAL FLUTE!!!!!”

So Lizzo showed up. She played the flute in a masterfully choreographed press event. As cameras recorded the musician performing in the elegantly pillared and arched Great Hall of the library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, Hayden could not shake a vision of the instrument falling, shattering on the marble floor. (That did not happen.)

The next night, the crystal flute was escorted by three Capitol police officers to the Capital One Arena. It was handed to Lizzo onstage where between songs, in bejeweled combat boots and a sequined bodysuit, she gingerly carried it to the microphone. She played a long, trembling note that concluded with a look of shock. She played a second trilling note. The audience roared.

“Thank you to the Library of Congress for preserving our history and making history freaking cool,” she told the crowd.

A childhood full of music

Hayden was raised by music. Her father, a violinist, started the strings department at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee. Her mother was a classically trained pianist who taught music at the local elementary school. Hayden would sit under her mother’s piano and play as her parents rehearsed tunes together.

In 1957, when Hayden was 5, her father moved the family to New York City, where he joined Nat and Cannonball Adderley on the local jazz circuit.

But Hayden was drawn to books. Her parents could look at sheet music and hear a tune, and Hayden could look at printed pages and hear a voice. She would surround herself with books at the counter of the candy shop after school.

It never occurred to her, though, to become a librarian. She majored in political science and history at Roosevelt University in Chicago, where she had moved with her mother at age 10 after her parents divorced.

Upon graduation, unsure whether to pursue a law degree or a master’s in social work, Hayden applied to jobs as she tried to make up her mind. When she wasn’t interviewing, she would retreat to the central branch of the Chicago Public Library downtown. It was there one day that she ran into a college classmate who asked if she was applying for one of the open library positions. They’re hiring anybody, he told her.

Hayden was assigned as a library associate to a storefront branch on 79th Street. It was 1973. She knew nothing about being a librarian except the stereotype—glasses, hair in a bun, spinster, demure. Her first day she found her new colleague Judy Zucker, a white woman in jeans sitting on the floor reading books to a group of autistic Black children.

“She was just really cool,” Hayden says.

As she watched Zucker reading to children, she realized the potential held within every library. The vocation, in her eyes, opened beyond its quotidian lending role and became a quiet engine of betterment in the world, a source of water and light for undernourished communities.

It didn’t hurt that the workplace was full of books.

The Library of Congress employs roughly 3,000 people and operates with a budget of more than $800 million. It houses the U.S. Copyright Office and serves as the main research arm for members of Congress. It is the nation’s oldest federal cultural institution. To lead the library is to lead a large, balkanized bureaucracy that is accountable to political personalities and full of employees who have worked there for decades.

Change does not come easily; Hayden’s career has proved to be good training for the job.

Inspired by Zucker, Hayden applied to the University of Chicago for her master’s degree. She continued working in the public library system during her studies, even as she went on to pursue doctoral research in children’s literature; her dissertation focused on how museums serve children.

After completing her Ph.D. in 1987, five years before the University’s Graduate Library School closed, she was hired to teach library science at the University of Pittsburgh. Four years later she was recruited to her first leadership role, as head of the Chicago Public Library, which was completing construction of a new main branch downtown.

With that job, “Carla walked into an extremely difficult diplomatic environment,” says James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, who, at the time, sat on the council overseeing the new library’s development. The building had been commissioned by Mayor Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor, in July 1987. Mayor Washington died a few months later, and the project became not only about creating a library but about crafting a monument to Washington’s life.

When Hayden arrived in Chicago in 1991, Mayor Richard M. Daley had been voted into his second term, and relations between his administration and the council members who wanted to preserve Washington’s legacy were, to put it lightly, strained.

“Distrust remained very potent and very visible, barely beneath the surface,” Grossman says.

Hayden still got things done. Despite swaggering egos and political feuds, she kept city administrators and library council members focused on the work of completing the library. Doors opened in October 1991.

“I should also say that everybody in that room liked Carla,” Grossman says. “That is not an insignificant accomplishment.”

Effectiveness and charm are two traits widely acknowledged by those who know Hayden. “She is a constellation of talent, determination, grace, and experience,” says Betsy Hearne, AM’68, PhD’85, who served on her dissertation committee at UChicago.

Hayden is soft-spoken, often reaching to touch those she knows on the upper arm in a warm, familial gesture. And she possesses a preternatural willpower, seemingly always capable of closing the gap between a vision and its realization.

She left Chicago after just two years, poached by Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library. The Pratt system is famous among librarians. It was one of the first free public libraries in the country and has a long history of inclusivity. It set a model that Andrew Carnegie followed when building his network of libraries. But the Pratt had fallen into decline, as Baltimore’s industrial base hollowed and its population contracted.

The main library, an architectural marvel in its day, was a faded light. “The grand lady had fallen into disrepair, and it was like, c’mon,” Hayden says.

So, she started cleaning. With staff, she swept floors, updated bookshelves, moved furniture. She uncovered an iconic window and its grillwork on the building’s second floor. And then began the difficult work of both reviving and updating an institution where circulation, employee morale, and funding had all slipped.

Within a year, one of her colleagues was quoted in the Baltimore Sun describing Hayden’s leadership as “somewhere between excellent and magnificent.” During her second year at the Pratt, she was named Librarian of the Year by Library Journal. The Pratt became the first library in Maryland to offer free internet access.

Then she introduced other innovations: lawyers visited neighborhood branches to advise on civil legal issues and record expungement. The library reached out to social workers at the University of Maryland, who began offering services in library branches in 2017. In food deserts, the library took grocery orders and had the food delivered to the local branch.

As a trained children’s librarian, Hayden reinvigorated the library’s youth services. More times than she could count, she had seen libraries change a child’s life. She had seen them save a child’s life. “I saw it happen at the Whitney Young branch in Chicago,” Hayden says. “I saw it happen all the time in Baltimore.”

After more than 20 years guiding Baltimore’s Pratt system, Hayden captured national attention in April 2015, when Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old Black man, was arrested and sustained fatal injuries to his spine during police transport. Baltimore came to a boil. The day of Gray’s funeral, peaceful protests turned to violence, and Hayden called Melanie Townsend Diggs, then manager of the Pratt’s Pennsylvania Avenue branch. Hayden had a question: A crowd was approaching the library. What was the plan?

Townsend Diggs locked the doors and turned out the lights. She had security officers dress in plain clothes. Several cars and a CVS across the street were set ablaze. The staff and patrons filed unnoticed out a side door. Another question: What happens tomorrow?

Townsend Diggs and her staff discussed it with Hayden and decided to keep the library open. Hayden arrived the next morning carrying fruit, flowers, coffee, Danish, cups, plates, and water. She praised the staff for their courage. Patrons went about their business. A man applied for a job and landed an interview. Groups of children entered, many hungry, as the schools where they ate breakfast and lunch were closed. Food donations rolled in; tutors showed up. Reporters arrived to charge their phones.

There is a picture of Hayden from that day, near legendary within the library world. It shows her at the front door of the Pennsylvania Avenue branch posting an “open” sign on the front door. She is recognized and celebrated throughout Baltimore for revitalizing the Pratt during 23 years of leadership and, more broadly, for her service to the city.

White House calling

Hayden was already part of a team consulting with the Obama administration about the Library of Congress’s technology investments when the White House personnel division got in touch. They asked if she would like to “consider being considered” to lead the Library of Congress. There is no higher perch for a librarian, but she hesitated.

More than anything, Hayden loved the profession of librarianship as an act of service. “The place of the cure of the soul,” read the inscription above the shelves in the Library of Alexandria. In the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, inmates took solace in a secreted copy of Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain.”

“It comforted me in my despair; it told me that I was not alone,” one prisoner recalled.

How, Hayden wondered, could an institution as large, as physically and psychologically distant as the Library of Congress touch individuals so deeply?

This was the same question that President Barack Obama asked during her interview. He wanted to know how she would connect the country to itself through the library’s treasures.

Today she has many answers to that question. Hayden speaks, for example, of a moment standing beside a young girl at the Pratt’s Pennsylvania Avenue branch, looking out the window as protests flared. What’s the matter? the girl asked. Why is everyone so upset? Hayden wishes she could have immediately responded by pulling up a scanned version of Rosa Parks’ papers—specifically, a note Parks wrote recalling her anger at a white boy during an encounter from when she was about the girl’s age. Not an answer, but a connection.

Despite being the first African American to become librarian of Congress, Hayden speaks little in public about the country’s relationship with race. But this relationship has affected her life. She grew up hearing from her mother about the Whites-only water fountains that were still around when Hayden was a toddler in Tallahassee.

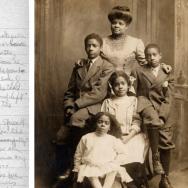

As a young girl, she came across a family photo of her teenaged uncle in a casket; the public story was suicide, but she learned he’d been shot by a white shop owner because the shop owner’s daughter found him attractive. And when she was 18, Hayden went to a Jackson 5 concert in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood; she and her friends were chased to the doors of the music venue by a group of white junior high kids.

“What’s so powerful about Carla—what I just love, to be honest—is her ability to be fearless and strategic, to recognize that part of the job of institutions like ours is to be the glue that holds the country together,” says Lonnie Bunch III, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. “But you can’t [do that] if you don’t illuminate the dark corners.”

Hayden knows that our country emerged and continues to create itself through a vast tapestry of efforts, most invisible, and that we are better for recognizing this fact.

Look where we have come

At her swearing-in ceremony on Sept. 14, 2016, Hayden chose to recite her oath with a hand on Lincoln’s bible. She was stepping up to direct the country’s great emblem of knowledge as a descendant of people who were legally punished with lashes and amputations if they were caught learning to read.

To prepare her speech, she began to research every law forbidding an enslaved person’s pathway to literacy. She decided she would enumerate these laws at the ceremony, one by one. Her mother suggested this approach might be something of a downer at an otherwise joyous occasion.

At the podium, Hayden opted for a brief summary of the issue. She highlighted the distance between the historical sufferings of people who looked like her and the moment everybody was there to celebrate.

As librarian of Congress, she has now become both a representative and a narrator of our country’s progress. “History is a long haul,” she says. “Times we’re going through now, yes, they’re kind of rough, but there have been other rough times, and look at what’s happened and where we’ve come.”

Hayden still lives in Baltimore. On the days she commutes to Washington by train, she reads. The day of her confirmation vote, as the Senate tallied its yeas and nays, librarians held watch parties to learn the outcome, but Hayden, too anxious, went home with her mother and waited. In the early afternoon, the 51st vote came in, nudging her into the new job.

A hard rain was falling as she and her mother held hands and stood in Hayden’s solarium, absorbing the moment’s significance. Her mother said to her: “Those are the tears of your ancestors.”

—This story was first published in the University of Chicago Magazine.