There are lots of ways to make a living as a clam, but probably one of the strangest is to be a “living drill bit.” Some species of clams are able to bore into solid rock or concrete—creating a burrow in a substance that is harder than their own shells.

Studying these clams, however, scientists noticed something odd about their evolutionary patterns. When an organism breaks into a new niche, it often results in a burst of new species; but even though “living drill bits” repeatedly evolve over the course of history, they never seem to flourish. Scientists suspect they aren’t the only example—and it may have implications for our understanding of evolution as a whole.

The study by David Jablonski, the William R. Kenan, Jr., Distinguished Service Professor of Geophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago, along with Stewart Edie at the Smithsonian and Katie Collins at the Natural History Museum in London, was published online in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

‘Boring but never tedious’

Scientists have catalogued about 200 species of clams that can bore into hard surfaces. Some are attracted to coral reefs or wood (causing problems for navies throughout history), but others head for solid rock.

Some clams release chemicals to burrow into wood, coral or soft limestone. But harder stone like granite requires a different approach. These clams generally start with a small crack or crevice as newly settled larvae, and slowly wedge their way in, bracing their bodies against one edge and levering their shell to chip off bits of rock as they grow. Some even trap bits of rock or hard minerals in the shell, increasing the abrasion they can bring to bear. The end result is a burrow that resists wave turbulence and most predators.

For years, Jablonski’s lab has studied bivalves – the category that includes all clams, such as scallops, mussels, and cockles -- as a way to understand the evolution of species over time, uncovering clues about the forces that shape bodies and lifestyles over time.

For this study, he worked with Edie and Collins to catalogue all the known species and fossils of these “boring” clams.

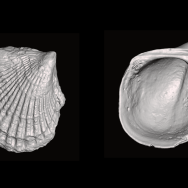

The adaptation has independently evolved at least eight separate times; Collins and Edie made 3D scans of 75 species descended from all eight, along with 310 species in the same lineages but following more traditional bivalve lifestyles, and tracked down the oldest fossil members of those lineages.

The first thing that surprised the scientists was that these borers have a broad variety of shell forms, from long tubes to spheres “like little shelled golf balls,” said Edie. “It’s surprising they don’t all converge toward some single, optimal design."

The scientists also noticed something odd about the patterns of evolution. The borer lifestyle occurs throughout nearly the entire span of bivalve history—the first borers appeared nearly 450 million years ago—but no species has ever taken off afterward.

“Instead, they tend to originate and then peter out, or at least never do anything special in terms of diversity, each time,” said Jablonski.

Normally, explained Jablonski, when an organism evolves some new advantage, the number of species tends to rise dramatically, sometimes explosively. “Birds evolve flight, and they take off, so to speak,” he said. “We think this process results in much of the evolutionary diversity we see around us.”

But that doesn’t happen to the borer clams.

“In that sense boring is a dead end, sometimes even an evolutionary failure,” said Edie. “It attracts evolutionary linages, but they don’t show any special tendency to diversify once they’re there.”

This puzzled the scientists. “There’s clearly a short-term evolutionary advantage, or it wouldn’t have evolved so many times in such widely separated lineages,” Collins said.

“There must be some additional contingency that holds them back,” suggested Edie, “some limitation of their environment, perhaps? We’ll need to test that next.”

The scientists suspect this failure to capitalize on evolutionary novelty isn’t limited just to borer clams. For example, even though there are what Jablonski called “a multitude” of ants in the world, anteaters have evolved but never really taken off or diversified.

It’s possible that identifying and studying these anomalies may lead scientists to new understandings of evolution, the scientists said.

“There are so many forces at play whose interactions we still don’t understand,” said Jablonski, “but it’s important if you want to explain why the world looks the way it does—and what it might look like in the future.”

Said Collins: “They may be boring bivalves, but they’re never tedious.”

Citation: “Convergence and contingency in the evolution of a specialized mode of life: multiple origins and high disparity of rock-boring bivalves.” Collins, Edie, and Jablonski, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Feb. 8, 2023.

Funding: National Science Foundation, NASA.