The questions Prof. David Jablonski asks aren’t the little ones.

“How do you go from a monkey hanging out in a tree, to an organism who can build electric guitars, and air conditioners, and trains, and airplanes?” he asks.

“For that matter, why are there so many species of ants and so few species of elephants?” Jablonski continues. “Why are we here and the dinosaurs aren’t?”

Jablonski’s questions have shaped the modern approach to the fossil record and changed the landscape of evolutionary biology. For this, the Linnean Society of London recently presented him with the Darwin-Wallace medal for his innovative research and unique perspective. Only three other paleontologists have received the medal since it was first awarded in 1909.

Jablonski is a paleontologist, but he doesn’t work in a paleontology department. Instead, he serves as the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Geophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago. This is deliberate; he believes the only way to answer these kinds of big questions is to draw from multiple fields.

‘It changed my life’

Jablonski’s approach to evolutionary biology is reflected in the path he took to get there. “I’m one of those kids who got hooked on dinosaurs at about the age of 5,” Jablonski says. “The American Museum of Natural History was my babysitter.”

He attended New York’s Columbia University for his bachelor's degree, where he worked hands-on with the specimens he grew up studying behind glass at the museum.

He began his first paleontological endeavor while at Columbia. “I edited an encyclopedia of paleontology, 700 pages long. I know: insane. I got it started as an undergraduate, and I ended up knowing everybody in the field.”

One paleontologist he discovered was University of California-Berkeley Professor James Valentine.

“Valentine wrote a book about how the world works, about the evolutionary ecology of the ancient world,” Jablonski says. “I read it in college, and it changed my life.” The book, ‘Evolutionary Paleoecology of the Marine Biosphere,’ challenged the bounds set by classical paleontology and sparked field-wide controversy.

“At the time, most people were going out and discovering new dinosaurs and adding them to the scientific literature. Valentine, instead, put everything together, and asked questions about how communities changed,” Jablonski explains. “These were the kinds of questions I wanted to answer.”

Inspired, Jablonski stepped up as a leader of the emerging movement in paleontology alongside Valentine.

Studying mass extinctions

Jablonski fought many of his paleontological battles on the front of mass extinctions–periods in geologic time where biodiversity decreases rapidly as many species go extinct simultaneously. Evolutionary biologists are often interested in periods of mass extinction because the typical rules governing competition and evolution are flipped on their heads.

“I showed that mass extinctions don’t necessarily select on the same traits that are selected on during normal times,” he says. “My study provided a means for how species selection might actually work in practice, as opposed to simply raising the possibility that was true.”

He is known for a concept he calls “dead clade walking”–the realization that not all lineages that survive a mass extinction participate in the subsequent recovery. Another line of inquiry showed that whether lineages survive extinctions can be driven by factors beyond short-term selection based on an organism’s traits–for example, the larger a species’ geographical range, the more likely it is to survive a mass extinction.

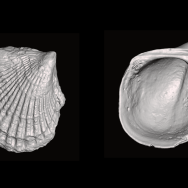

Because Jablonski likes to look with a birds-eye view at the evolutionary process—for example, building extensive maps of mollusc fossils over time—patterns often appear. He showed that disturbed onshore habitats are often a spark for major evolutionary novelties, which then spread offshore over millions of years. He also used the maps to addressing a decades-old controversy in evolution about whether tropical seas were unusually likely to host new species or simply more likely to preserve them.

Instead, Jablonski says: “It’s a false dichotomy; these seas can be both a cradle and a museum of biodiversity.”

He has recently become interested in how animals develop new “ways to make a living”—that is, what and how they eat and live—especially in the wake of extinction events. “We need to stop looking at just one dimension of biodiversity at a time—species numbers, biological form, and ecologies need not change in lockstep, especially when the big changes hit,” he says.

This research, Jablonski says, is important for understanding not just past dynamics, but also the future of biodiversity as we undergo a mass extinction-level event.

His group has even pioneered ways to predict current extinctions in the species that are harder to track. “The conservation status of marine species is so much harder to evaluate than species on land,” he says. “Big-picture data and insights from the fossil record can help set conservation priorities.”

And that group, Jablonski argues, has been essential for the progress and breadth of his research.

“Contrary to what most people think, science is an incredibly social enterprise,” he says. “I’ve been unbelievably lucky in my students, postdocs, and collaborators. We push each other to break new ground, in the most positive and creative ways. It’s a blast and I’m always learning something new.”

‘Look again’

Jablonski helped cement the shift in the field by taking paleontological approaches to classical questions about evolution. Modern paleontology is more integrated with other branches of biological science, due in part to Jablonski's work.

As paleontologists uncover more about our natural history, Jablonski urges them not to be afraid to ask the foundation-shaking questions. “If a senior scientist says that something can’t be true, look again!” he says. “New ways of analyzing data, and new, bigger datasets, might tell a different story.”

Big questions are the trademark of David Jablonski, and without them, the field of paleontology would not be what it is today.