There are extinctions, and then there’s the “Great Dying.” That was the Permian-Triassic extinction around 250 million years ago, which wiped out nearly all life on Earth.

Scientists have been modeling the results of this and many other extinctions to understand how life on Earth responds to challenges, but a new study finds that a common methodology may obscure the true picture of which species and lineages are destroyed during mass extinctions—and which survive and evolve.

Published Dec. 1 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the study evaluated hundreds of species of fossil clams to piece together a comprehensive evolutionary tree over hundreds of millions of years. University of Chicago scientists—along with colleagues at the Smithsonian Institution, the UK’s Natural History Museum and the Field Museum—found that one basic assumption made in most models can significantly distort the evolutionary picture, causing the scale of evolutionary recovery from a massive extinction to be off by as much as 400%.

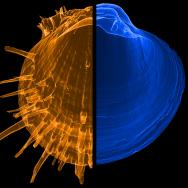

This particular assumption is that when a new species is created, it splits the lineage into two new species—rendering the original species extinct. For example, a clam known as Species A might split into Species B and C, and species A is considered extinct.

But it’s possible that sometimes a new lineage “buds” off an existing lineage. In this scenario, clam Species B might be born even as Species A continues to exist.

This subtle distinction appears to have a big impact, however: “Depending on what assumptions you bake into the model, you can wind up with two totally different pictures,” said David Jablonski, the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Service Professor of Geophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago and a senior author on the paper.

“There are many really important questions locked up in these evolutionary trees,” said Nick Crouch, a UChicago postdoctoral researcher and corresponding author of the study. “They underpin almost every evolutionary study out there right now. To say anything meaningful about evolution, we need to accurately know when lineages originate and when they go extinct.”

Cultivating evolutionary trees

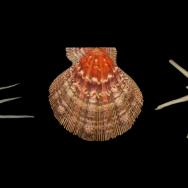

For many years, scientists could only turn to fossils to piece together the history of evolution over time. Fossils are extraordinarily useful, but there are many kinds of creatures that don’t fossilize easily. “I study clams so I have tons of fossils, but my colleagues studying, say, jellyfish or fruit flies, aren’t so lucky,” said Jablonski.

But then came a marvelous boon for scientists: the ability to analyze DNA.

As DNA is passed down, it changes slightly over time, acquiring new mutations and retaining bits of older generations. By studying the DNA of a modern-day organism, scientists can make all sorts of estimates about its evolution—including what its evolutionary tree might look like, even if we don’t have any fossils.

However, there are a lot of assumptions built into that type of analysis, including the question if new species “bud” or “fork” off the original branch. Scientists debate how much these assumptions affect results, but Crouch, Jablonski and their collaborators wanted to run an experiment to see exactly how this might reverberate over time—by creating a very thorough evolutionary tree of a big group that does have a good fossil record, and comparing the results between different assumptions of how lineages originate.

Jablonski studies bivalves, a type of aquatic mollusk that includes scallops, oysters and mussels. These organisms all have hard shells that fossilize readily, so there is an extensive fossil record from all over the world, extending over the past half-billion years.

Jablonski and Crouch worked with Field Museum curator Rüdiger Bieler, former UChicago doctoral student Stewart Edie, PhD’18, and former UChicago postdoc Katie Collins to develop a comprehensive picture for all bivalves, covering the 97 major families and 525 million years. “It did involve a certain level of extreme obsessiveness,” Jablonski admitted.

This process gave them a solid understanding of what the bivalve family tree likely looked like in reality. Then Crouch ran the numbers using the “forking” assumption common to so many DNA studies, and then ran them again with the “budding” approach.

They found a huge difference. “You might not expect a simple decision to have that big of an effect,” Jablonski said. “But it turns out if you force that assumption on your data, you really lose some of the big picture.”

Assuming that lineages always fork when they diversify tended to push the origins of new lineages further back in time than the fossil record indicated. For example, if you see Clam A and later clams B and C, the forking assumption says that clams B and C must have both originated at the first time you see clam B appear in the fossil record, because new lineages always arrive in pairs. But in reality, clam C may not have evolved until much later—so forking tends to start new lineages earlier.

This is particularly bad if it spans a period of mass extinction, because the splitting approach hides the true effects of that extinction and the rebound that follows.

“From fossils, we see a dramatic evolutionary burst after a mass extinction like the one at the end of the Mesozoic Era, when the dinosaurs went down and the descendants, the birds, took off, along with mammals like us,” said Jablonski. “But the splitting approach tends to make that diversification seem to happen earlier and more slowly than it really did, so it distorts the picture around mass extinctions and their aftermath.”

For example, the forking method suggests that seven major lineages emerged after the extinction at the end of the Mesozoic. But the fossil record says it was 28. “That’s a four-fold difference,” Jablonski said.

This is troubling, because mass extinctions are an important element in how biologists understand evolution, Crouch said: “Mass extinctions are incredibly influential in shaping biodiversity. You get lineages that are completely wiped out, and entirely new ones that emerge in response. They are a major factor in evolution.”

However, by using an evolutionary model that allows for budding instead of splitting, the scientists got a picture that much more closely matched the fossil record.

The scientists hope the results will help researchers improve all DNA-based tree studies, but especially those with less robust fossil records. This includes many types of life, from mosses to squids to birds.

The work, which was funded by NASA and NSF, was only made possible by collaboration, the scientists said. “This group brings researchers together across a huge range of fields. That led to a really powerful set of analyses,” Jablonski said, citing in particular UChicago’s Committee on Evolutionary Biology. “We couldn’t have done it without this teamwork.”

Citation: “Calibrating phylogenies assuming bifurcation or budding alters inferred macroevolutionary dynamics in a densely sampled phylogeny of bivalve families.” Crouch et al, Proceedings of the Royal Academy B, Dec. 1, 2021.

Funding: NASA, NSF.