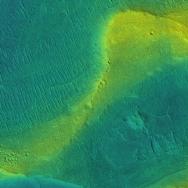

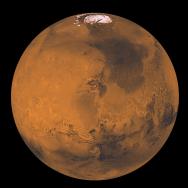

For centuries, miners have burrowed into the earth in search of salt—laid down in thick layers from ancient oceans long since evaporated. When scientists saw huge deposits of salt on Mars, they immediately wondered whether it meant Mars too once had giant oceans. Yet it’s remained unclear what those deposits meant about the Red Planet’s climate.

A new study by UChicago researchers shakes up the picture of Martian salt—and offers new ways to test what Mars’ water would have looked like.

“They’re not in the right places to mark the deaths of oceans, but they date from when Mars’ climate transitioned from the early era of rivers and overspilling lakes to the cold, desert planet we see today,” said study author Edwin Kite, assistant professor of geophysical sciences at the University of Chicago and an expert in both the history of Mars and climates of other worlds. “So these salt deposits might tell us something about how and why Mars dried out.”

The salt in Martian deposits isn’t the same as the salt of Earth’s oceans—it’s actually more similar to Epsom salts, made out of two ingredients: magnesium and sulfuric acid. Figuring out how those two chemicals combined can give us information about what Mars’ climate used to look like.

One possibility is that Mars had water that circulated deep underground, carrying magnesium to the surface where it reacted with sulfuric acid. That means the planet would have been warm enough to allow groundwater to flow.

The other option is that the magnesium was simply blown in as dirt. In this case, the climate could be as cold as the coast of Antarctica.

Kite’s team focused on the groundwater scenario, building models to see whether it would be realistic. The researchers’ analysis zeroed on the fact that there’s so much Martian salt that it couldn’t been deposited as a one-time dry-out—the water would have to repeatedly pick up salts, evaporate, turn back into liquid water, and repeat the cycle. Each time this happened, as the water drained into the ground, it would have carried out a little bit of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere with it.

The problem is, while too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere warms the planet—as we’re finding out on Earth—too little will freeze it. If too much carbon was locked into the ground and the resulting atmosphere was too thin to keep Mars warm, the groundwater movement would halt as the planet froze. And the analysis found the cycle would lock up a lot of carbon.

This doesn’t sound promising for the groundwater scenario, Kite said, but it doesn’t disprove it. “Most of our model runs disfavored groundwater, but we also found a few ‘loopholes’ that could allow Mars to keep enough carbon in the atmosphere,” he said.

Fortunately, there would be signals that NASA’s Curiosity rover (currently on Mars) could test when it arrives at a salt deposit—hopefully in 2020.

“Curiosity has an excellent instrument package, so it’s possible we could get some very interesting data,” said study co-author Mohit Melwani Daswani, formerly a postdoctoral researcher at UChicago now at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Citation: “Geochemistry constrains global hydrology on Early Mars.” Kite and Melwani Daswani, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Oct. 15, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2019.115718

Funding: NASA