One hundred years ago, on July 10, 1925, the trial of John T. Scopes began.

It concluded 11 days later with a conviction. Today, this battle in the conflict over religion and science in United States classrooms is perhaps best remembered for its climax—the ruthless dissection of prosecutor William Jennings Bryan by Scopes’s counsel, Clarence Darrow, dramatized in fictional form in the 1960 film Inherit the Wind.

Nearly forgotten is the role of a half dozen University of Chicago professors and alumni—experts in religion, biology, geology, anthropology and education. This group played a key part in the defense, so impressing Scopes with their body of knowledge that he himself would later go on to study at the University.

In May 1925, Scopes, X’31, was the first person charged for violating a Tennessee law making it illegal for any teacher in a state-supported school to teach “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

He was a science teacher at Rhea County Central High School in Dayton, a Tennessee town of 1,800 people located 40 miles north of Chattanooga.

For two weeks he took over a biology class for an indisposed colleague, teaching from a text that discussed evolutionary theory. Acquaintances in Dayton persuaded him to submit to arrest. They were critical of the law but mostly eager to draw attention—and business—to their sleepy little town. And so began the circus known from its inception as the “Monkey Trial.”

Bryan was chosen to assist the prosecution. Three times the Democratic Party nominee for president, he now fashioned himself as a defender of the Christian faith and warned of “the menace of Darwinism.”

His participation attracted Darrow, a Chicagoan at the pinnacle of his career as the “attorney for the damned,” who volunteered for the defense.

“I knew that education was in danger from the source that had always hampered it—religious fanaticism,” he explained. Darrow had earlier tangled with Bryan over religion, posing some 50 questions to him about the literal truth of the Bible on the front page of the Chicago Tribune.

Darrow intended to prove, as historian Adam Shapiro, AM’03, PhD’07, has noted, that the Tennessee law improperly favored a “fundamentalist” interpretation of Scripture over all others. To make his case, Darrow needed expert witnesses to testify not only to the scientific truth of evolution but also to the compatibility of evolutionary theory with other Christian beliefs. He found several close at hand.

Darrow lived in an apartment on 60th Street near Stony Island Avenue. He hosted an informal biology club there, directing discussions on biology, religion and evolution from his rocking chair. The participants included many UChicago professors.

Soon after taking the case, Darrow rang up Fay-Cooper Cole, an anthropology professor and a biology club contributor.

“I suppose you have been reading the papers, so you know Bryan and his outfit are prosecuting that young fellow Scopes,” Cole recalled him saying. “Well, [a few of us] have put ourselves in a mess by offering to defend. … We need the help of you fellows at the University, so I am asking three of you to come to my office to help lay plans.”

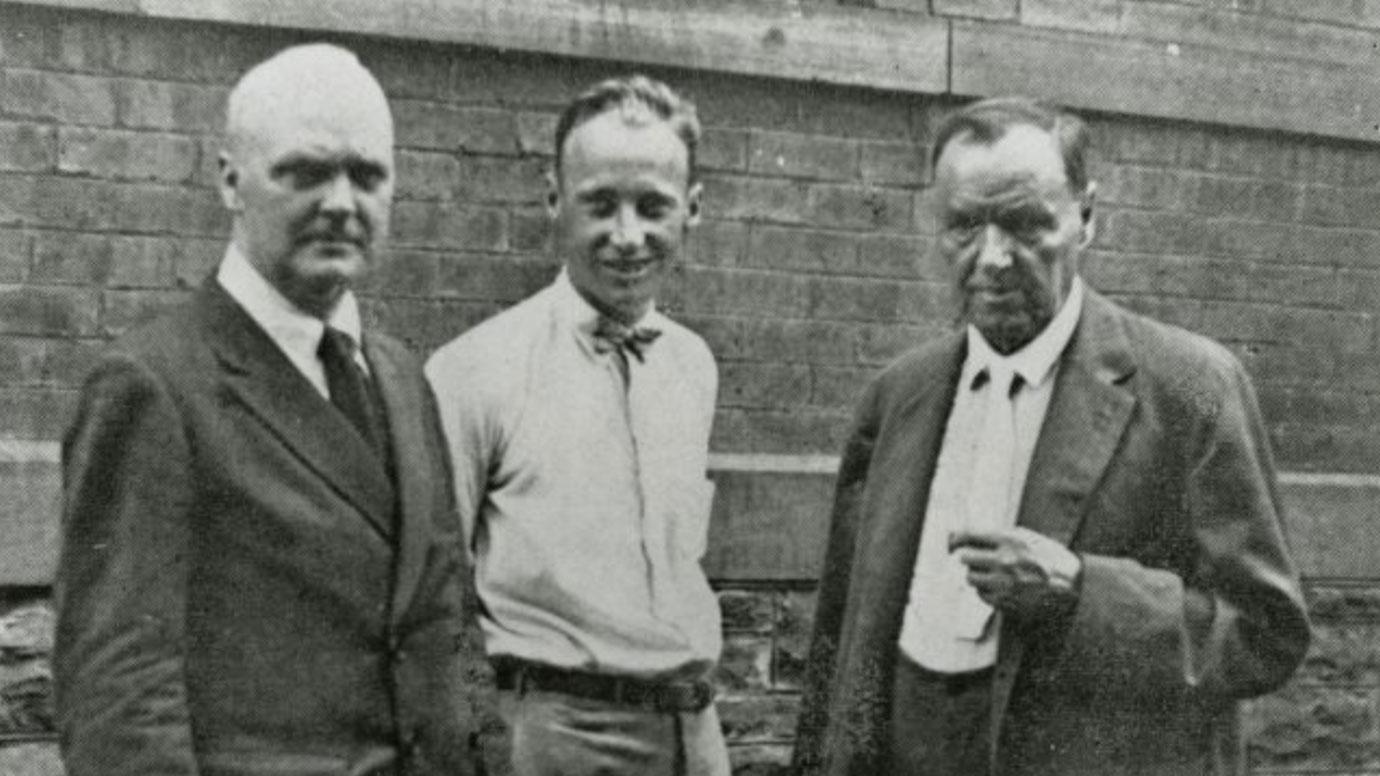

Later that day, Darrow met with Cole; Horatio Hackett Newman, PhD1905, a zoology professor; and Shailer Mathews, dean of the Divinity School, to outline the strategy for the trial.

In 1925, Cole was a new associate professor. He had joined the faculty the year prior after 19 years at the Field Museum, where he oversaw the program in physical anthropology, the study of the hominid fossil record. In addition to dean, Mathews was professor of religious history and comparative theology.

He was a leading proponent of theological “modernism” and the editor of and a contributor to the 1924 collection Contributions of Science to Religion. Mathews saw no conflict between the two.

“Science warrants religion,” he wrote, “because it affords evidence of immanent reason, purpose and personality in the cosmic environment and its discovery of the laws of human life.”

Meanwhile, Newman was an embryologist—evolutionary theory was at the center of his work.

The other witnesses for the defense were a rabbi and Hebraist, two ministers, the state geologist of Tennessee, two additional zoologists, an agronomist, an academic geologist and an educational psychologist. The psychologist, Charles H. Judd, was a professor and the director of the University’s School of Education. The geology professor was Kirtley F. Mather, PhD1915, a petrogeologist at Harvard University and a Chicago native.

In addition to their scholarly credentials, the five Chicago experts on Scopes’s team had another qualification essential to Darrow’s defense: staunch familial, educational, professional and, in some cases, continuing connections to evangelical Protestant churches. Cole, Newman, and Judd were ministers’ sons. Mathews’s grandfather was a Baptist pastor. Mather was descended from the famous family of Puritan preachers.

All five had attended Baptist or Methodist colleges. Mathews was a theologian, and Mather a lay leader in his church. Mathews, Newman, and Mather were on record supporting the compatibility of evolutionary theory and Christian belief. Mather joined the defense to make the point.

“Somebody ought to be in Dayton to defend a religion that would be respectable in the light of modern science,” he decided, “and I thought I knew what that religion was.”

Other than Mathews, who submitted his testimony by telegram from the Chautauqua Institution in New York, the defense witnesses stayed in a big Victorian house on the edge of Dayton.

H. L. Mencken, who reported on the trial, described the house as “ancient and empty … now crudely furnished with iron cots, spittoons, playing cards and the other camp equipment of scientists.” It was called the Mansion, Defense Mansion, and, inevitably, the Monkey House.

“Few, if any, of these witnesses will ever get a chance to outrage the jury with their blasphemies,” Mencken continued, “but they are of much interest to the townspeople. The common belief is that they will be blown up with one mighty blast when the verdict of the twelve men … is brought in, and Darrow [and the other defense attorneys] with them. The country people avoid the Mansion. It is foolish to take unnecessary chances.”

For all their learning, wisdom, and commitment, the witnesses for the defense had no material effect on the outcome. Judge John T. Raulston ruled their testimony irrelevant to the question at hand—whether Scopes had violated the statute. However, he allowed the defense to put the experts’ statements in the court’s record, and these were widely reported in the press.

Two days later, the jury returned its verdict in nine minutes. Judge Raulston fined Scopes $100.

The Scopes Trial brought notoriety not only to Scopes and Darrow but also to the witnesses. Soon after returning to Chicago, Cole received a summons from Frederic Woodward, a law professor acting as UChicago president after the death of Ernest DeWitt Burton. Woodward showed him resolutions from a Southern Baptist convention condemning him for his involvement in Scopes’s defense.

As Cole read their complaints he began to laugh, but Woodward caught him short.

“Already we have more demands for your removal than any other man who has been on our faculty,” Woodward told him.

In fact, he continued, the Board of Trustees had discussed the allegations. Suddenly sober, Cole asked about the reaction. Woodward handed him a piece of paper.

“They had raised my salary,” Cole later recounted.

As the trial neared its end, Scopes had assessed his options. He decided not to return to his teaching job, and he rejected lucrative offers to cash in on his fame on the lecture circuit. To help him out, the scientists took up a collection that garnered Scopes enough money to support two further years of schooling.

After considering law school, he realized that the trial had sharpened his “old interest [in] science.”

“One of my most valued windfalls at Dayton had been listening to … the distinguished scientists who had stayed at the Mansion,” Scopes said. “They had broadened my view of the world and everything in it.”

When Mather interviewed him about his plans, Scopes affirmed his interest in graduate study. Would he study “botany or zoölogy” Mather asked.

Neither, was the reply: “I’d like to study geology.” And at “what graduate school?” “The University of Chicago—if you don’t mind, Professor Mather.”

“Of course I don’t mind,” Mather responded. “My own geological training was at the University of Chicago, and I think that’d be very fine indeed.”

In September 1925, Scopes boarded an Illinois Central train at his parents’ hometown of Paducah, Kentucky. Clarence and Ruby Darrow met him at the 63rd Street stop, and he boarded with them until he was able to rent a room.

In addition to three graduate courses in geology, The Daily Maroon reported, Scopes audited a course offered to first-years “on the inter-relationships of science”; the lectures by Newman were of special interest to him. Hundreds of newspapers ran the story of the educator prosecuted for teaching evolution now sitting as a student in an evolutionist’s course.

Scopes did his best to affect the obscurity of a graduate student. He was a denizen of the science library and a study room in Rosenwald Hall. He took a room in Gates Hall and then boarded in the house of the Gamma Alpha graduate men’s scientific fraternity. He attended get-togethers hosted by Darrow, where he got to know Cole and Newman better.

When a reporter intruded on him in 1926, Scopes was curt.

“I don’t want any more publicity,” he objected. “I am studying geology and one or two other scientific subjects. I think this is a good school and I should like to be let alone.”

In 1927, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled on his appeal, upholding the law but vacating the fine. The prosecutor terminated the case, precluding further appeals.

“Checkmates,” the Chattanooga News editorialized.

Scopes’s interests converged on paleontology, the study of the fossil record. He was elected to Kappa Epsilon Pi, the geology honor society and the science honor society Sigma Xi. In his second year, as his grant drew down, the department chair nominated him for a fellowship to support the completion of his doctorate. The president of the “well-known technical school” that administered it, however, refused to consider the application.

“As far as I am concerned,” he wrote Scopes, “you can take your atheistic marbles and play elsewhere.” Crestfallen and out of money, Scopes took a job with Gulf Oil in Venezuela.

Three years later, having lost the job, he came back to Chicago. His intended adviser had died in the meantime, but he found a new one, Edson S. Bastin, SM1903, PhD1909, in the new field of economic geology. His notoriety having faded, the press hardly noticed.

By the time he took additional courses and conducted fieldwork in New Mexico, however, “my Venezuela money [had] played out and with the end nearly in sight I had to stop and attend to needs considerably more pressing than the quest for a doctoral degree.”

Scopes never got his Ph.D. He eventually found a new job as a geologist, working in the oil and gas industry, living in Houston, Texas, and Shreveport, Louisiana.

In 1959, UChicago convened a conference to mark the centennial of the publication of On the Origin of Species and the sesquicentennial of Charles Darwin’s birth. Some 2,000 scientists, scholars, educators and journalists attended the five-day event in Mandel Hall. The chair of the conference planning committee, Sol Tax, PhD’35, did not invite Scopes to participate. His trial came up just twice in the discussions.

Scopes did return to UChicago the next year. He was the featured guest at the premiere of a film documenting the Origin centennial conference. After the screening, Scopes, Tax, four professors and the sales manager of the UChicago Press discussed the status of evolution in science teaching in the United States.

“A man’s fate, shaped by heredity and environment and an occasional accident, is often stranger than anything the imagination may produce.”

The law against teaching evolution was still on the books in Tennessee, a participant pointed out, as were laws in Mississippi and Oregon besides. (They overlooked a 1927 Arkansas statute copied nearly verbatim from Tennessee’s. Arkansas’s ban on teaching evolution, and others like it, were invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1968.)

In other states, textbook publishers resorted to euphemisms to finesse the controversy surrounding the concept. Away from teaching for a third of a century, Scopes had little to add.

“I hope that I don’t ever have to go through something like that again” was nearly all he would say about his experience in Dayton.

Scopes was more reflective in his 1967 memoir. In the contrast between scientific and religious perspectives on evolution, he found an apt metaphor.

Despite the brevity of the event in the course of his life, he wrote, “in many minds I’ll always be John T. Scopes, the Dayton, Tennessee, teacher who was the defendant in the Monkey Trial. … A man’s fate, shaped by heredity and environment and an occasional accident, is often stranger than anything the imagination may produce.”

—Adapted from a story originally published in the UChicago Magazine