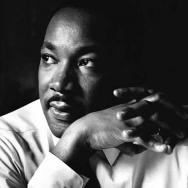

Few figures in our history have been as attuned to the power of media as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The civil rights leader, with his immediately recognizable cadence and likeness, was an orator who was keenly aware of how to use the camera to advance a cause. Studying Dr. King’s legacy through that lens was the focus of Prof. Jacqueline Stewart’s keynote address at the University of Chicago’s Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration on Jan. 28 at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel.

“Dr. King understood the tremendous power of the image, including the moving image, to shape public opinion as well as self-perception,” said Stewart, a renowned film scholar and the former director and president of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. “He leveraged media, especially photojournalism and television, to raise awareness and empathy, to bring evidence in front of indifferent and even hostile White audiences.”

Over the course of her address, Stewart brought her expertise as a film historian to explore Dr. King’s legacy. Stewart, the Edward Carson Waller Distinguished Service Professor in Cinema and Media Studies at UChicago and founder of the South Side Home Movie Project, guided the audience through clips from major documentaries and fictional films, amateur footage shot by everyday Chicagoans and archival newsreels—tracing how King appeared on screen during his lifetime and how filmmakers have grappled with his legacy since.

President Paul Alivisatos and Rockefeller Chapel Dean Maurice Charles also spoke at the 36th annual event, which featured performances from the youth choir Uniting Voices Chicago. In his remarks, Alivisatos described how television captured Dr. King’s “indelible images of courage” as a civil rights leader.

“Without such documentation, we might never have known, or we might be apt to forget, the hard-earned lessons of that era,” he said.

Aliviastos similarly underscored the power of media in today’s digital world.

“It has never been easier for one person to make a video and document their experience, what they are living through, and to share what they witness,” Alivisatos said. “We should handle the present media that we observe with the same care with which we handle history. Our responsibility is not just to consume media as it unfolds each day, but to seek to interpret it and sometimes connect it to a larger understanding of our society … to weigh our civic duty to engage in shaping the world as we want it to be.”

Shaping King’s public persona

King’s relationship to cinema, Stewart explained, began in childhood. In 1939, a 10-year-old King sang with the Ebenezer Baptist Church choir at the Atlanta premiere of Gone With the Wind—a massive media event of its day.

Stewart noted that King’s father, himself a major civil rights leader in Georgia, may have recognized that the only way Black residents of Atlanta could be visible at such a landmark moment was “through the prism of Hollywood’s fantasies.”

As King established his public persona, she explained, he understood he would need to speak to multiple audiences simultaneously, which required careful attention to how he presented himself on camera.

King and his colleagues capitalized on television’s saturation into homes across the U.S., leveraging what were then the only three networks’ hunger for dramatic material. King also realized that televised images of peaceful protesters facing brutal repression could shift public opinion in ways that speeches alone could not.

Stewart quoted King’s own words after the violent crackdown on Selma marchers in 1965: “We are here to say to the White men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television.”

She also highlighted the 1970 Madeline Anderson documentary I Am Somebody, which captures Coretta Scott King addressing striking hospital workers. Stewart used the film to discuss the legacy of Scott King—both in relation to her husband but also as she established her own voice and presence. In fictional portrayals, Stewart said Scott King’s role as a confidant and partner was often undersold, given her shared life of danger and sacrifice.

Stewart paid particular attention to Ava DuVernay’s 2014 film Selma. She praised the film’s efforts to highlight the roles of women in the movement, as well as its imaginative attention to period detail and DuVernay’s composition of King-like speeches written to capture “the spirit” of the historical moments.

“DuVernay wants to draw out the complexities of King's leadership and the many relationships that shaped his work,” Stewart said, “and she seeks to give us more points of entry into and identification with the familiar archival footage of these landmark moments of collective bravery.”

Home movies of Dr. King

Some of the keynote’s most personal moments came from amateur and local news footage preserved in Chicago archives, including from Chicago Film Archives, the Media Burn Archive and the South Side Home Movie Project, which Stewart founded in 2005 to collect film captured by local residents.

One donated reel documented a family trip to Memphis just weeks after King’s 1968 assassination. In grainy footage, a small girl stands over the eternal flame lit in King's honor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, her head bowed, her fist raised.

Stewart concluded with TV news footage from the 1966 Chicago Freedom Movement rally at Soldier Field. It featured King speaking about the slow pace of progress, the persistent forces opposing racial equality, the urgent need to vote. The footage is unpolished, but even with its rawness Stewart said something essential comes through.

“King’s masterful oratory, his understanding of the power of not just his voice but his image,” she said, “reaches us across time with remarkable prescience and conviction.”

—Video highlights of the MLK commemoration will be available at a later date.