Immunotherapies have emerged as an effective way to treat cancer. Scientists are very hopeful about these new treatments, which use the body's own defense system to shut down cancer.

Several kinds of immunotherapies are already being used to treat certain types of cancer. Ongoing research, including at the University of Chicago, may reveal more possibilities.

Jump to a section:

- What is cancer immunotherapy?

- How does immunotherapy work?

- What are the main types of immunotherapy?

- What are the benefits of immunotherapy?

- Can immunotherapy be used for other diseases besides cancer?

- What are the side effects of immunotherapy?

- What research is happening at the University of Chicago in immunotherapy?

What is cancer immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy is a treatment that strengthens the ability of the patient’s own immune system to detect and destroy cancer.

Cancer cells often have mutations that allow them to escape the immune system. Immunotherapy drugs are designed to boost the cancer-fighting powers of immune cells in order to give the immune system the upper hand.

Although the principles of immunotherapy have been around for a long time, the field has gained momentum during the past decade due to multiple scientific advancements. Based on the overwhelmingly successful results of a number of clinical trials, Science named cancer immunotherapy the “Scientific Breakthrough of the Year” in 2014. Researchers hope they can effectively treat cancer with fewer side effects than other treatments.

How does immunotherapy work?

It is normal for cells to grow and divide, but there are processes within cells that tell them to stop growing. When these processes fail, cell growth can go haywire. These abnormal cells can develop into cancer and overtake healthy organs and tissues, eventually spreading outside the immediate area to other parts of the body.

Usually, the immune system detects and destroys abnormal cells and keeps the growth of potential cancer cells in check. The immune system consists of white blood cells and the organs and tissues of the lymphatic system, such as the thymus, spleen, tonsils, lymph nodes, lymph vessels and bone marrow.

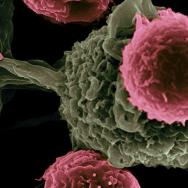

However, cancer cells sometimes acquire clever ways of avoiding destruction by the immune system. Because cancer cells originate as normal cells, the immune system doesn’t always recognize them as foreign. Cancer cells can also take advantage of genetic changes that make them invisible to the immune system; they can contain proteins that “turn off” immune cells; or they can alter how the immune system responds.

To overcome this, researchers have found ways to help the immune system detect and attack cancer cells, just as it would viruses, bacteria or other foreign invaders.

What are the main types of immunotherapy?

There are several different kinds of immunotherapies currently used to treat cancer. Two main types are checkpoint inhibitors and cellular immunotherapy.

Many cancer immunotherapies rely on the activation of T cells—a kind of immune cell that can recognize specific markers on tumor cells and attack them. One way that cancer cells escape T cells is by sending false signals to immune cell “checkpoints” to make themselves look harmless. A class of drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors block these false signals, so the immune system isn’t tricked into ignoring tumors.

This discovery was so important that, in 2018, American immunologist James P. Allison and Japanese immunologist Tasuku Honjo were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for their work that led to the development of checkpoint inhibitors.

Another type of immunotherapy known as cellular immunotherapy uses the “Trojan horse” concept to overcome cancer. Immune cells are taken from a patient’s body, modified in a lab, and replaced back into their body in large numbers to help the immune system fight cancer.

One example is CAR T cell therapy, which takes a patient’s T cells and adds a gene called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR. When the modified T cells are placed back in the body as CAR T cells, they’re “supercharged” to recognize cancer cells and fight them. This therapy gives adults and children with blood cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma, a promising new treatment option. (The University of Chicago Medicine was the first site in Illinois to offer this therapy in 2017.)

What are the benefits of immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy has emerged as a breakthrough in cancer treatment. Unlike other forms of treatment, immunotherapy is attractive because it can offer the potential for remarkable results with far fewer side effects.

A growing number of people with cancer have benefited in recent years from immunotherapy, with some seeing dramatic and lasting responses to these new treatments. In rare cases, patients with advanced cancers have had their tumors disappear completely following treatment with immunotherapy.

Can immunotherapy be used for other diseases besides cancer?

Although immunotherapy is primarily used in cancer, it is also used to treat autoimmune diseases and disorders. Researchers, including at UChicago, are exploring how immunotherapy may be used for genetic disorders, inflammation, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and regenerative medicine.

What are the side effects of immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy has fewer side effects than most cancer treatments because it specifically targets the immune system and not any other cells.

Still, some patients experience side effects triggered by an overly active immune response. These side effects can affect any tissue or organ in the body, and can range from mild to moderate to severe. Under certain circumstances, these effects can become life-threatening.

Fortunately, as long as the potential side effects are recognized and addressed early, in most cases they can be managed safely with immunosuppressive drugs such as steroids. Therefore, every patient undergoing immunotherapy needs to be continuously monitored for side effects or reactions that may develop.

Despite some incredible successes of immunotherapy, it is not effective for all tumor types or all patients. No two cancers are alike, and genetic, biological and environmental factors can make some people less likely to respond to immunotherapy.

What research is happening at the University of Chicago in immunotherapy?

Many immunotherapies have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and are used today to treat cancer, sometimes even as the initial course of treatment. However, more research needs to be done to understand how the immune system works at the molecular level and how it can be leveraged to develop new therapies.

Immunotherapy research has a long history at the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center, dating back to the work of Dr. Frank Fitch in the late 1980s that demonstrated the potent ability of T cells to reject deadly tumor cells.

Researchers at the University of Chicago were early to understand that although many patients do mount an initial immune response against tumors, that work is often not completed due to processes that turn off or dampen the immune response. These biological processes are critical to prevent autoimmune diseases like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis; unfortunately, these checks on the immune response also help cancerous cells evade destruction.

More than two decades ago, UChicago researchers began testing “cancer vaccines” that aimed to elevate a person's level of antigen-specific T cells. These are specific white blood cells that can recognize antigens, or short protein fragments displayed on the surface of cancer cells. The scientists observed that some people already had elevated levels of these specific T cells in their blood prior to vaccination, and the vaccine was ineffective at sparking a response in others.

The question became, how do you overcome this barrier and develop better therapies that can help more patients?

Scientists at UChicago uncovered several factors that play a role in a patient's response to immunotherapy. For example, Thomas Gajewski, professor of pathology and medicine, recently found that a person's gut bacteria may impact the effectiveness of certain immunotherapies.

Another key player is the tumor “microenvironment”— the cellular environment in which a tumor lives. The microenvironment consists of tissue, blood vessels, immune cells, fibroblasts, and other components that interact with tumor cells. These pieces play an important role in how tumors behave and their susceptibility to certain drugs. Gajewski coined the term "T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment" to describe a major subset of tumors from patients whose cellular environments make them more likely to respond to immunotherapies.

Today, research continues around the University of Chicago, including at the Chicago Immunoengineering Innovation Center, the UChicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of Chicago Medicine Etta and David Jonas Center for Cellular Therapy, which was established in 2020 with a $10 million gift from the Jonas family to accelerate progress in realizing the full potential of cellular therapy.

Last reviewed June 2025.