The night sky is a natural time machine, used by cosmologists to explore the origins and evolution of the universe. Reaching into the depths of the past, a class of undergraduate students at the University of Chicago sought to do the same—and uncovered an extraordinarily distant galaxy in the early cosmos.

Light emitted from faraway celestial objects takes a long time to reach Earth-side observers. That means the stars and galaxies we see in the sky appear to us as they would have existed millions, or even billions, of years ago.

The discovered galaxy’s light comes from a time when the universe was only 1.2 billion years old, about one-tenth of its current age. By this point, the young galaxy had already accumulated a mass impressively comparable to the present-day version of our home galaxy, the Milky Way.

“This galaxy that we’ve observed, by looking out and back into the past, is already grown up. It’s already formed almost a Milky Way’s worth of stars,” said Michael Gladders, a professor in UChicago’s astronomy and astrophysics department. “It’s quite mature, but at a much earlier stage in the Universe.”

The discovery was a climactic milestone in the first iteration of a field course developed for the new astrophysics major offered by UChicago. Students in the two-quarter class formed a new research collaboration, COOL-LAMPS, and surveyed public imaging databases in search of lensed galaxies. The remarkable find was confirmed by observations from ground-based instruments: the Magellan Telescopes in Chile and the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii.

‘Nature’s telescope’

A lensed galaxy is one whose emitted light has been bent by the gravity of a massive object lying between the galaxy and the point of observation. This effect, known as gravitational lensing, creates a distorted, arc-like image of the galaxy with an intensely magnified brightness.

Gladders, who taught the field course in the first half of 2020, calls gravitational lensing ‘nature’s telescope.’ “It’s a rare, peculiar form of focusing and magnification that allows us to study galaxies with much greater detail than we ever normally could,” he said.

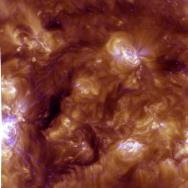

Light from the discovered galaxy was so strongly magnified by a cluster of other galaxies in its foreground that it rivaled images of the sky taken from space.

“This was a ground-based telescope taking data of this absolutely beautiful arc,” said Gourav Khullar, a UChicago PhD candidate who served as teaching assistant for the field course and is first author of the paper describing the findings. “It’s approximately a hundred times brighter than classical images of similarly distant galaxies from the Hubble Space Telescope!”

A comprehensive study of the stellar populations of this galaxy, undertaken by the student collaborators, concluded in the realization that this was the brightest lensed galaxy ever observed in this time period of the early universe.

Without gravitational lensing, though, the distant galaxy would appear much dimmer, if visible at all.

“The arc has been magnified by the intermediate lens in such a way that it’s extremely bright,” said Khullar. “But an un-lensed version of the galaxy wouldn’t look like this; it would be much fainter and not at all detectable by current ground-based facilities.”

Pushing through the pandemic

The field course was designed to provide astrophysics majors with a real-life, cutting-edge research opportunity. Originally modest in ambition, Gladders convinced the department and the College to invest in a complete field experience, including a visit to the Magellan Telescopes to participate in astronomical observing time over spring break.

But the coronavirus pandemic thwarted those plans, ripping away what was intended to be the core experience of the class.

“Everything was booked,” said Gladders. “I’d already arranged trips to other observatory sites, construction sites to see telescopes that were currently being built, and to see Chile itself.”

In the midst of dark times, the COOL-LAMPS students pushed on with the scan of public sky data, eventually reaching their illuminating galactic discovery.

“For me, it was a shock that we had found something so important,” said Emily Sisco, a fourth-year astrophysics major who participated in the field course during the last academic year. “All of the work we had been doing was leading up to that moment, but I was still shocked!”

Intriguing first results have encouraged the COOL-LAMPS collaboration to pursue observation time for a second wave of study. Plans are set to observe the galaxy using ground-based telescopes in New Mexico and Europe, as well as two of NASA’s orbiting space telescopes, Hubble and the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

“With higher resolution imaging from space, astronomers will be able to resolve the structure of this galaxy,” said Ezra Sukay, who joined the COOL-LAMPS collaboration as a third-year student in the College. “This will reveal details about star formation in very massive galaxies early in the Universe.”

Gladders expected the class to be successful in some way, but did not anticipate a galaxy so exceptionally bright, far back in time, or mature as what was discovered. “It’s just absolutely fantastic,” he said. “I’m so proud of them—they’ve done really great work.”

In January, Gladders will begin teaching a second version of the field course, adding new students to COOL-LAMPS who will continue to probe the formation and evolution of galaxies across cosmic time.

“One of the great goals in studying the cosmos is answering the fundamental question of where we come from,” said Gladders. “Us as a species, but also the planet we live on, the solar system that planet is in, and the galaxy that our solar system is in.

“We’re addressing this deep yearning to understand where it all comes from and ultimately, how do we fit in?”

COOL-LAMPS is short for ChicagO Optically-selected strong Lenses – Located At the Margins of Public Surveys. The UChicago undergraduate authors of the paper are Katya Gozman, Jason J. Lin, Michael N. Martinez, Owen S. Matthews Acuña, Elisabeth Medina, Kaiya Merz, Jorge A. Sanchez, Emily E. Sisco, Daniel J. Kavin Stein, Ezra O. Sukay and Kiyan Tavangar.

The study also includes co-authors from the University of Michigan, the University of Cincinnati, Argonne National Laboratory, Harvard University, the University of Oslo, the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Citation: “COOL-LAMPS I. An Extraordinarily Bright Lensed Galaxy at Redshift 5.04.” The COOL-LAMPS Collaboration, Nov. 12, 2020. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2011.06601.pdf

Funding: University of Chicago College Innovation Fund, Office of the Provost and the Chicago Center for Teaching (2020 Inclusive Pedagogy Grant).