If you’ve ever sat waiting at the doctor’s office to give a blood sample, you might have wished there was a way to find the same information without needles.

But for all the medical breakthroughs of the 20th century, the best way to detect molecules has remained through liquids, such as blood. New research from the University of Chicago, however, could someday put a pause on pinpricks. A group of scientists announced they have created a small, portable device that can collect and detect airborne molecules—a breakthrough that holds promise for many areas of medicine and public health.

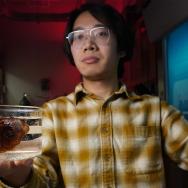

The researchers envision the device, nicknamed ABLE, could detect airborne viruses or bacteria in hospital or public spaces, improve neonatal care or allow people with diabetes to read glucose levels from their breath. The entire device is just four by eight inches across.

“This project is among the most exciting endeavors we've pursued,” said UChicago Prof. Bozhi Tian, one of the senior authors on the paper. “There are so many potential applications. We’re delighted to see it come to fruition.”

The study is published May 21 in Nature Chemical Engineering.

Turning air to liquid

For decades, our ability to detect molecules in air has lagged behind our ability to detect the same ones in a liquid. Hence the blood tests at the doctor’s office, and the pinpricks people with diabetes often undergo daily. Even the home COVID tests you may have taken all involve adding droplets of liquid.

“We can use cell phones to take pictures or record audio, but we don’t have similar technology to see the air chemistry,” said Jingcheng Ma, the first author of the study, who was formerly a postdoctoral researcher at UChicago and is now assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame.

Part of the trouble is dilution. In air, the particles you’re looking for—such as a few viruses floating around—might be as few as one in a trillion. That’s a tall task for a detector, and until now it has required large, expensive equipment.

A team of UChicago scientists set out to solve that problem by finding a way to turn air into liquid, making it easier to read.

The team designed a multipart system. First, a pump sucks in the air for the reading. Next, a humidifier adds water vapor, and a miniature cooling system lowers the temperature. This causes the air to condense into droplets—with any relevant particles suspended inside. The droplets slide down a specially designed ultra-slick surface and collect into a small reservoir.

From there, detectors can easily pick up the concentrations of molecules in the liquid, using pre-existing and readily available equipment for liquid detection.

As they put together the device, they weren’t sure whether they would be able to capture some types of molecules that evaporate easily, known as “volatile” molecules.

For one early proof of concept, Ma used a cup of coffee as a test. He blew a puff of vaporized coffee into the system to see if it could be successfully collected and detected. When the liquid condensed out, he didn’t even need to run tests to know it had worked—the distinct aroma of coffee emanated from the liquid.

In further tests, they found they could successfully detect glucose levels from breath, detect airborne E. coli and pick up markers of inflammation from the cages of mice with poor microbiome gut health.

They named the system ABLE, for Airborne Biomarker Localization Engine.

New abilities

The initial inspiration for the study, Tian said, was a trip he made years ago to the Stephen Family Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at UChicago’s Comer Children’s Hospital as a part of his ongoing work with the Center for the Science of Early Trajectories. The center founder, Prof. Erika Claud, wished there was a way to run tests on her tiny patients without drawing blood or other invasive methods.

Claud, who is the Section Chief of Neonatology and the Stephen Family Professor in Pediatrics, now hopes to be able to put this newly developed technology to use.

“Premature infants are some of the most vulnerable and fragile patients that we care for in medicine,” she said. “The promise of this technology is that we will be able to non-invasively track newly identified biomarkers, to optimize care for these infants.”

The researchers can also imagine many other uses. But there’s a challenge—the ability to easily detect airborne molecules is so new that scientists don’t even yet know what molecules they would need to look for.

For example, the group is now collaborating with a doctor who treats inflammatory bowel disease. It’s likely you could detect markers of inflammation from the breath of patients with IBD, but they would first need to be catalogued.

The team also wants to refine the design and miniaturize it further to make it wearable.

Finally, Ma, a mechanical engineer who has a background in thermofluidics, is excited about the implications for revealing new principles of physics.

“This work might start many new studies on how these airborne impurities affects phase change behaviors, for example, and the new physics can be used for many applications,” he said.

University of Chicago scientists Megan Laune, Pengju Li, Jing Lu, Jiping Yue, Yueyue Yu, Jessica Cleary, Kaitlyn Oliphant and Zachary Kessler were also co-authors on the study.

The researchers are working with the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation and the Center for the Science of Early Trajectories.

Citation: “Airborne biomarker localization engine for open-air point-of-care detection.” Ma et al, Nature Chemical Engineering, May 21, 2025.

Funding: U.S. Army Research Office, University of Chicago, University of Notre Dame, Technology Development Fund from the Berthiaume Institute for Precision Health, Grier Prize for Innovation Research in the Biophysical Sciences, National Institute of Health.