A handful of soil is not only a miracle to a farmer, but also an engineer: “It can respond to a range of stimuli,” said chemist Bozhi Tian. “If you shine light or heat on it, if you step on it, if you add water, if you add chemicals—the soil changes in response and in turn, this affects the microbes or plants living in the soil. There are so many things we can learn from this.”

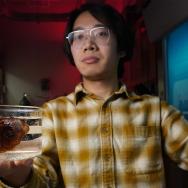

Tian and his laboratory at the University of Chicago are taking inspiration from nature to engineer new systems with a range of potential applications. Their latest experiment mimics the structure of soil to create materials that can interact with their environment, with promise for electronics, medicine, and biofuel technology. It has multiple potential applications; preliminary tests have shown the material can boost the growth of microbes and may be able to help treat gut disorders.

In a study described in Nature Chemistry, the team designed a springy substance composed of tiny particles of clay, starch, and droplets of liquid metal. The clay and starch create structure with lots of nooks and crannies, but it’s flexible enough that the material can also adapt and respond to the conditions around it.

Much like real soil, these nooks and crannies create the perfect spots for microbes to flourish. “We found the porosity is very important; we call it the partitioning effect,” said Tian. “I think of it like a meeting—if you break a large meeting or class into smaller sections there will be more interaction.”

Microbes often get a bad rap, but there are many times when we actually want microbes to grow. For example, doctors think that digestive diseases like colitis partially stem from a lack of diverse microbes in the gut, so a goal of medicine is to boost them. In fact, preliminary tests showed the new “soil” material reduced symptoms of colitis in mice.

Microbes can also be put to work producing molecules such as biofuels, which are used as a renewable alternative to fuels like gasoline. Tian’s lab found that their material encouraged the growth of the biofilms used in biofuel production. It may extend to other uses, too; “This is potentially a more environmentally friendly method to make various chemicals used in industrial production,” said Jiping Yue, a scientist in Tian’s lab and a co-first author on the study.

In the course of their experiments, the lab also found that the droplets of liquid metal boosted the growth of bacteria. “We’re not yet sure about the mechanism, but if you leave out the liquid metal, the biofilms and the gut microbiome diversity both drop,” said Tian. They theorized it could have to do with providing a source of metal ions, which are abundant in the body and used in enzymes.

Interestingly, the lab also found that they could make rewriteable circuits by burning patterns into the substance with a laser or drawing them with a pen. The heat or pressure causes the droplets of liquid metal in the substance to melt and join together, forming lines of conductivity. This circuit can then be undone chemically. “That means it is a rewriteable memory; you could think of using this approach for constructing a neuromorphic computing chip from soil-like materials,” said Yiliang Lin, the lead author of the study, formerly a postdoctoral scholar at UChicago and now an assistant professor at the National University of Singapore.

Moreover, Tian is excited about the nature-inspired approach.

“Soil is just the beginning; if you think about this as a bigger picture, there are many other places to get inspiration,” he said. “Can we use this knowledge to design new material or chemical systems? There are numerous ways we can learn from nature.”

The research made use of the University of Chicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC), the Electron Microscopy Service of the University of Illinois at Chicago, BioCryo facility of Northwestern University, and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source and Center for Nanoscale Materials at Argonne National Laboratory.

Citation: “A soil-inspired dynamically responsive chemical system for microbial modulation.” Lin et al, Nature Chemistry, Oct. 24, 2022.

Funding: U.S. Office of Naval Research, National Science Foundation, Zhong Ziyi Educational Foundation Award.