In a University of Chicago lab, a clear liquid pours into a beaker. Instantly, almost magically, the contents turn a rich blue color.

Once one of the most difficult colors to recreate in paint, blue was only available to medieval artists, for example, by grinding up the prized stone known as lapis lazuli. By the 1900s, it was still difficult enough to produce that inventor George Washington Carver received a patent for his process.

When artist Amanda Williams, LAB’92, stumbled across the obscure patent nearly 100 years later, she hoped to recreate his recipe and reached out to chemists at the University of Chicago for help.

“The synergy of those brains and points of view overlapping constantly was really interesting to see along the process," Williams said of working alongside UChicago science students. "There has to be some discipline, but there also has to be a little bit of risk. Innovation has to be a little bit of both of those things."

Out of the blue

Williams is in love with color. The artist and architect credits this early fascination to growing up when “Black” first became popular as a racial term. Since then, she’s been struck by the multifaceted nature of color—as material, as racial signifier, as emotion.

In her Color(ed) Theory series, Williams painted abandoned buildings on Chicago’s South Side in hues significant to the Black community, such as colors inspired by Pink Oil Moisturizer hair lotion and Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. The series’s cheeky humor celebrates cultural experiences Black Americans share, while highlighting systematic erasure and urban disinvestment.

Williams first came across Carver’s hue while conducting archival research into Reconstruction era patents. “What did Black people make when they didn’t have to just think about survival?” she wondered.

When a friend mentioned that Carver held a patent for blue pigment, Williams was shocked. “I said, ‘The peanut man?’”

More digging revealed that the Tuskegee University professor, though a prolific inventor, painter and Renaissance man, only held three patents with the U.S. government. One, from 1927, was for making blue pigment from iron-rich clay.

“He was using this Alabama red clay, which is in abundance in the soil on Tuskegee’s campus,” Williams said. “This idea of one of your source materials being free seems to reinforce a hypothesis that this is why the patent was necessary, because he was going to streamline the production.”

Williams thought, why not try to recreate it? However, Carver’s process would prove more complicated than following a simple recipe—some parts were intentionally vague to protect the patent.

During a chance meeting at the opening reception for the Smart Museum of Art’s Monochrome Multitudes exhibition—another celebration of color—Williams mentioned the project to University President Paul Alivisatos.

“We’d love to help,” Alivisatos said.

A pigment of the past

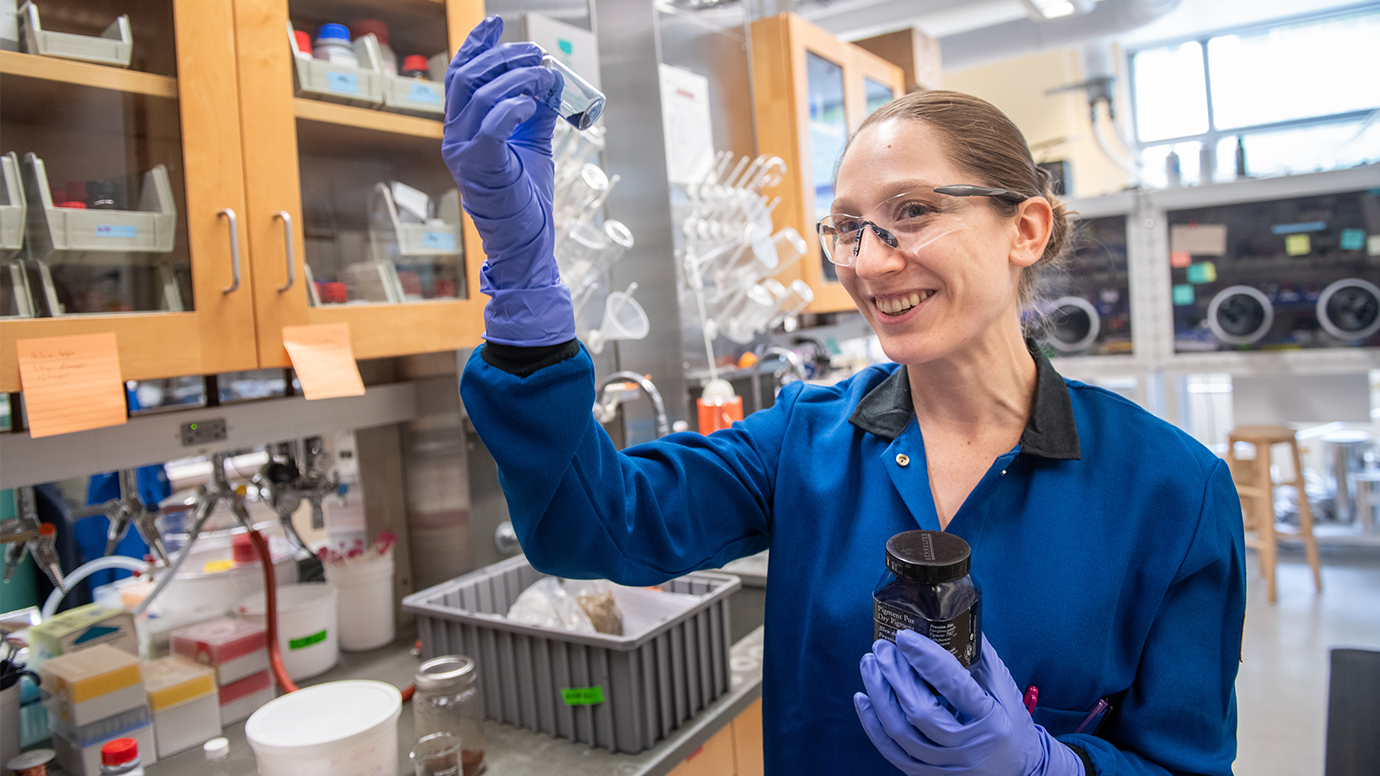

Reading over the 100-year-old original patent, chemist Amanda Brewer was shaking her head. It calls for very large quantities of very concentrated acids mixed together for months at a time.

“I was like ‘Oh my god, we’re not doing it in this exact form, just for safety reasons,’” said Brewer, a Ph.D. student and member of Alivisatos’ lab. “[Carver] must have been doing this outside, because it’s going to create fumes for months.”

Brewer, with the help of three undergraduate students—Sarah Thau ‘26, Nathan Behre ’24, as well as summer researcher, Nadia Ceasar—adapted Carver’s recipe to make it safer and more manageable.

The recipe calls for separating the iron from clay using strong acids. Then it’s mixed with other reagents, and the blue precipitates out—appearing dramatically from a mix of two yellowish solutions.

Experimenting with various soils, including jars of Alabama dirt sent by a cousin of Williams, the team consolidated the recipe to use just one type of acid. They also took advantage of modern equipment like centrifuges (normally used in the Alivisatos lab to isolate quantum dots) to more quickly separate out components.

By the end, the team had a reliable recipe that could be achieved in hours, rather than weeks to months.

To investigate the crystal structure of the blue pigment, Brewer tested samples using a technique called powder X-ray diffraction. They confirmed it was identical to “Prussian blue,” one of the first pigments achieved through modern chemistry, which caused a sensation when it was accidentally invented in the 1700s.

Curious about what kinds of clay could work in the recipe, the team also tested samples of soil from Bronzeville, a historically Black neighborhood in Chicago, and from the University of Chicago campus. All produced the same startling blue.

Thau said the effort has had a lasting effect on her perspective. “It’s the best project I could have hoped for as an undergrad,” said Thau. “It was so incredibly cool. And I notice color and pigment much more now. It’s around you all the time. It crops up in the oddest places. You’re painting your nails, or seeing a blue car on the street, and wondering how that pigment works.”

There is one other lasting consequence, however. Some parts of the chemistry lab are now permanently stained blue.

Painting the town

With the recipe in hand, a German manufacturer was able to scale up the process and produce 100 pounds of pigment for Williams’ studio so that she could experiment with the next step: turning the pigment into paint. Paint requires a binder, which can be anything from milk protein to eggs to oil; Williams decided to focus on milk, which is what Carver would likely have used.

Last year, for the New Orleans arts triennial Prospect.6, Williams used the paint to coat two buildings in Carver blue: an arts building at Xavier University and a shotgun-style house on the campus of the New Orleans African American Museum.

Williams wanted the structures to signal a pop of joy amidst the already color-saturated city, and also to highlight Black ingenuity.

“The level of effort Carver must have had to endure to even receive the patent was a testament to innovation and perseverance,” Williams said.

Williams continues to experiment with the pigment in her work. She recently opened a solo exhibition in New York City, titled “Run Together and Look Ugly After the First Rain,” a collection of 20 paintings and 10 collages using paint she created from the Carver blue recipe.

“George Washington Carver wanted to make sure knowledge extends itself, that it builds on a network of people learning from each other,” Williams said. “So, it's been really nice that the project, in some ways, embodies that at its elemental level.”