Quantum communication has the potential to become the ultimate secure communication channel. Not only is it nearly impossible to eavesdrop on quantum communication, but those who try will also leave evidence of their indiscretions.

However, the technology is still in its infancy. Sending quantum information over traditional channels, such as fiber-optic lines, is difficult: The particles—typically entangled photons—carrying the information are often corrupted or lost, making the signals weak or incoherent. Often, a message must be sent several times to ensure that it went through.

In a new paper, scientists with the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago have demonstrated a new quantum communication technique that bypasses these channels altogether. By linking two communication nodes with a channel, they show that this new technique can send information quantum-mechanically between the nodes—without ever occupying the linking channel.

The research, led by Prof. Andrew Cleland and published June 17 in the journal Physical Review Letters, takes advantage of the quantum phenomenon of entanglement between the two nodes, and shows a potential new direction for the future of quantum communication.

In another recently published paper, Cleland’s group entangled two phonons, the quantum particles of sound—a scientific breakthrough that opens the door to potential new technologies.

“Both papers represent a new way of approaching quantum technology,” said Cleland, the John A. MacLean Sr. Professor of Molecular Engineering at PME and a senior scientist at Argonne National Laboratory. “We’re excited about what these results might mean for the future of quantum communication and solid-state quantum systems.”

Ghostly quantum communication

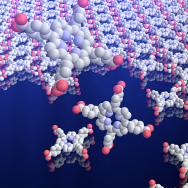

Entangled photons and phonons defy intuition. When these particles become quantum-mechanically “entangled,” the association can survive even though the particles themselves are separated over large distances. That is, a change in one particle elicits a change in the other. Quantum communication takes advantage of this phenomena by encoding information in the particles.

Cleland wanted to find a method to send quantum information without losing it in the transmission. He and his team, including PME graduate student Hung-Shen Chang, developed a system that entangled two communication nodes using microwave photons—the same photons used in cell phones. For this experiment, they used a microwave cable about a meter in length to establish the coupling between the qubits. By turning the system on and off in a controlled manner, they were able to quantum-entangle the two nodes and send information between them without ever having to send photons through the cable.

“We transferred information over a one-meter cable without sending any photons to do this, a pretty spooky and unusual achievement,” Cleland said. “In principle, this would also work over a much longer distance. It would be much faster and more efficient than systems that send photons through fiber-optic channels.”

Though the system has limitations — it must be kept very cold, at temperatures a few degrees above absolute zero — it could potentially work at room temperature with atoms instead of photons. For the moment, however, the cold version provides more control, and he and his team are conducting experiments that would entangle several photons together in a more complicated state.

Entangling phonons with the same technique

Entangled particles aren’t just limited to photons or atoms, however. In a second paper published June 12 in the journal Physical Review X, Cleland and his team entangled two phonons—the quantum particle of sound—for the first time ever.

Using a similar system built to communicate with phonons, the team—including former postdoctoral fellow Audrey Bienfait—entangled two microwave phonons (which have roughly a million times higher pitch than can be heard with the human ear).

Once the phonons were entangled, the team successfully performed a so-called “quantum eraser” experiment, in which information is erased from a measurement, even after the measurement has been completed.

Phonons do have disadvantages compared to photons; for example, they tend to be shorter-lived. However, they do interact strongly with a number of solid-state quantum systems that may not interact strongly with photons.

“It opens up a new window in what you can do with quantum systems, perhaps similar to the way gravitational wave detectors, that also use mechanical motion, have opened a new telescope on the universe,” Cleland said.

Other authors of the two papers include Y.P. Zhong, M.-H. Chou, C.R. Conner, E. Dumur, J. Grebel and R.G. Povey of the University of Chicago, and G.A. Peairs and K.J. Satzinger of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Citations:

- “Remote entanglement via adiabatic passage using a tunably-dissipative quantum communication system.” Chang et al, Physical Review Letters. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.240502

Funding: Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Army Research Laboratory, National Science Foundation, Department of Energy.

- “Quantum erasure using entangled surface acoustic phonons.” Bienfait et al, Physical Review X. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.10.021055

Funding: Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Army Research Laboratory, National Science Foundation, Department of Energy.

—This story was first published by the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering