The first cell phone, released in 1983, was the size of a brick and weighed two-and-a-half pounds. The newest Apple Watch, released this fall, weighs 1.1 ounces.

These kind of technological leaps have been made possible by finding new and inventive ways of combining materials, which can pack more information and circuitry into smaller and smaller packages.

In a first, scientists at the University of Chicago, in collaboration with researchers at Cornell University and Argonne National Laboratory, have discovered an easy, efficient way to grow extremely thin films of organic materials. The findings, published Nov. 7 in Science, could be a stepping-stone to future electronics or technologies with new abilities.

Scientists have known for a long time how to make extremely thin layers—down to a few atoms thick—out of inorganic materials. That’s how cell phones have shrunk in size and solar panels have sprung up on roofs around the world. But duplicating that manufacturing process with materials that are organic (in the chemical sense, that is, something containing carbon) has been tricky.

“If you can make materials into atomically thin layers, you can stack them into sequences and get new functions, and there are some great reasons to think organic films could be really useful,” said Yu Zhong, a postdoctoral researcher and co-first author on the paper. “But until now it’s been very challenging to control the thickness of the film, and to make them in large quantities.”

Luckily, chemistry and molecular engineering professor Jiwoong Park is an expert in pioneering new ways to make ultra-thin films—whether it’s sewing together crystalline sheets or stacking films like Post-Its.

“Until now it’s been very challenging to control the thickness of the film, and to make them in large quantities.”

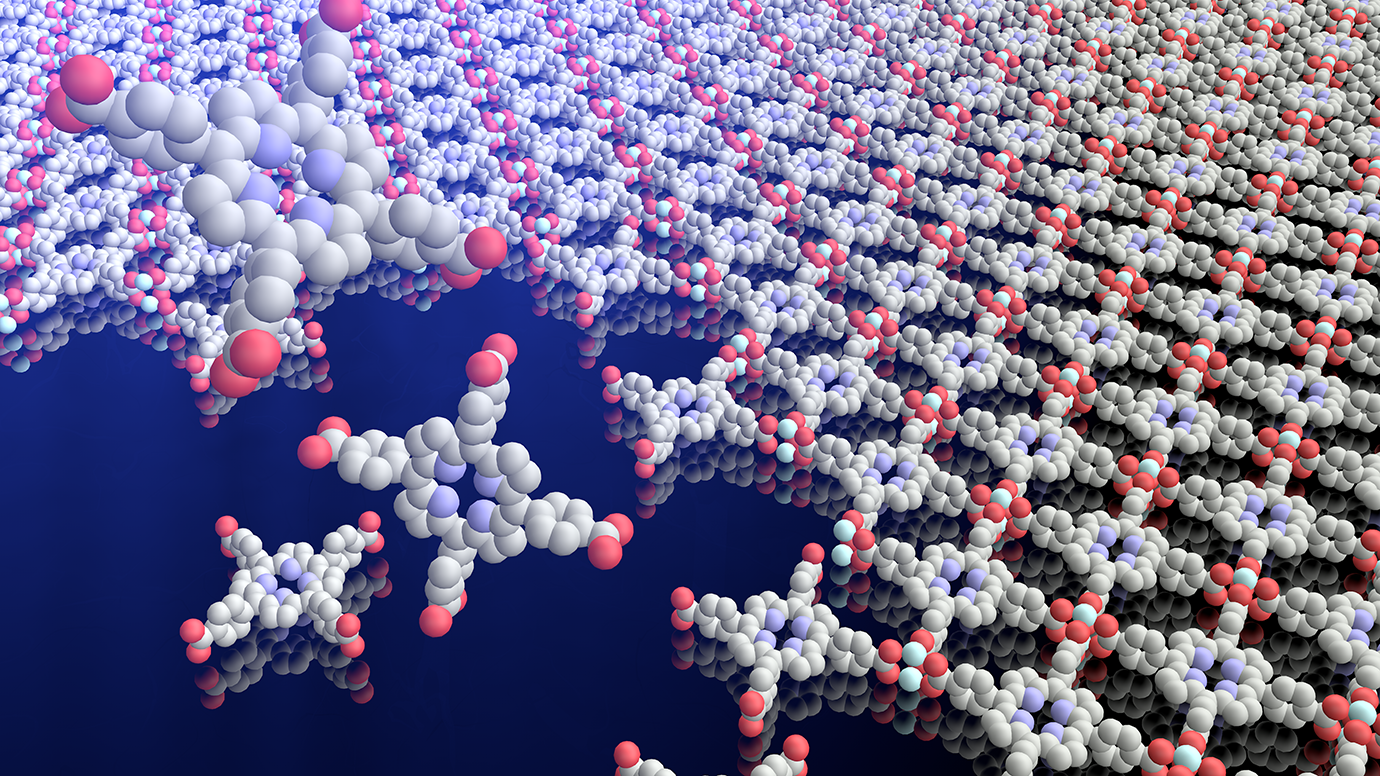

In this case, the team took its inspiration from the stubborn separation that happens when you mix two liquids that don’t mix, like oil and water. In essence, they used the line that forms between them like a mold to create a perfect thin, flat film.

They fill a reactor halfway with liquid A, then add liquid B. At the line where the two meet, they use a tiny tube to inject the rest of the ingredients, which assemble into a film. Then scientists evaporate or drain the liquids, and the film gently glides down to rest intact.

“If you think about it like cloth, to date, people have only been able to make patches—and these are gigantic rolls of fabric,” Park said.

Notably, the film grows in one continuous motion, so there are no awkward joints between patches. Additionally, it can be performed at room temperature, a much more efficient procedure than the extremely high temperatures usually needed to manufacture inorganic films.

The method also provides an innovative way to combine organic and inorganic layers. “Inorganic and organic materials have different strengths and weaknesses that could complement each other, but the conditions to grow them are so different that it’s been a challenge to make them get along,” said graduate student Baouri Cheng, the paper’s other co-first author.

In this method, though, “put an inorganic substrate on the floor of the reactor, and now you have a beautiful sandwich,” Park said.

They tested how the films work as electrical capacitors, and found good performance—a heartening sign for electronics.

But the team has many more ideas: nanorobots, a fabric that bends or straightens when exposed to water or light, membranes to filter water or boost batteries, sensors that detect toxins, and even bits for quantum computers of the future.

“This is really a demonstration of a general platform to integrate polymers,” Zhong said. “We can see a multitude of uses and opportunities, and we’re already investigating some of them.”

“If you think about it like cloth, to date, people have only been able to make patches—and these are gigantic rolls of fabric.”

UChicago postdoctoral researchers Chibeom Park, Andrew Mannix, Jae-Ung Lee, Joonki Suh and Kibum Kang and graduate students Fauzia Mujid, Sarah Brown and Kan-Heng Lee were also co-authors on the study, as well as Steven Sibener, the Carl William Eisendrath Distinguished Service Professor of Chemistry at UChicago; Professor David Muller and graduate student Ariana Ray at Cornell University; and Argonne National Laboratory scientist Hua Zhou.

The team used the University of Chicago Pritzker Nanofabrication Facility and Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, as well as the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Park is currently working with the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the University of Chicago to advance the discovery.

Citation: “Wafer-scale synthesis of monolayer two-dimensional porphyrin polymers for hybrid superlattices.” Zhong and Cheng et al, Science, 2019. DOI: 10.1126/science.aax9385.

Funding: Air Force Office of Scientific Research, National Science Foundation, Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy.