The hands of the Doomsday Clock are now at 100 seconds to midnight—the closest it has ever been to apocalypse since its creation following World War II.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which is housed at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago and whose board includes several UChicago scientists, announced the change during a Jan. 23 event in Washington, D.C.

In moving forward the metaphorical clock, which reflects the time humanity has left to avert a civilization-ending apocalypse, the Bulletin cited backwards moves on arms control from multiple countries, lack of action on climate change and the rise of ‘information warfare.’

Two years ago, the Bulletin moved the Doomsday Clock to two minutes to midnight—closer than it had been since 1953, when the United States and the Soviet Union successfully tested hydrogen bombs.

“We move the Clock toward midnight because the means by which political leaders had previously managed these potentially civilization-ending dangers are themselves being dismantled or undermined, without a realistic effort to replace them with new or better management regimes,” Bulletin officials wrote in a statement. “[We are] explicitly warning leaders and citizens around the world that the international security situation is now more dangerous than it has ever been, even at the height of the Cold War.”

In 2019, national leaders ended or undermined several major arms control treaties and negotiations, especially among the U.S., Iran and Russia. The Bulletin warned: “The world is sleepwalking its way through a newly unstable nuclear landscape.”

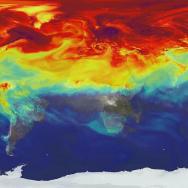

Leaders also failed to take steps appropriate to the “climate emergency” the world is in, even as devastating wildfires, floods and heat waves raged around the planet.

The organization also drew attention to the rise of information warfare, facilitated by the reach of the internet and an increase in politicians’ use of propaganda.

The Bulletin’s statement outlined concrete steps for both politicians and citizens to take to reduce these risks, including re-entering key arms control agreements, demanding action on climate change and creating international discussions on how to reduce disinformation.

“Past experience has taught us, even during the most dismal periods of the Cold War, we can as a people come together to address our challenges,” said Robert Rosner, the William E. Wrather Distinguished Service Professor in Astronomy & Astrophysics and Physics at the University of Chicago, who chairs the Bulletin’s science and security board. “It is now high time to do so again.”

The Bulletin was founded more than 70 years ago by Manhattan Project physicists, many of whom helped achieve the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction on Dec. 2, 1942 at the University of Chicago.

In the aftermath of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, they formed the Bulletin, which has been dedicated ever since to informing the public about technologies “with the potential to end civilization.” Though it began by focusing on nuclear war, its mission has expanded to address such global threats as terrorism, cyberattacks and climate change.

» Read about the founding of the Bulletin at the University of Chicago following World War II