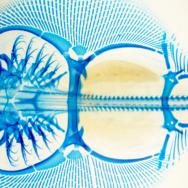

“Little skate” may sound humble enough, but this funny looking shark relative—with giant fins fused around its flat head—is aiming for the big time.

In the MBL Whitman Center lab, Tetsuya Nakamura and José Luis Gómez-Skarmeta are working on their goal to bring the little skate into the select group of animals—along with human, mouse and a a few others—whose full complement of DNA (genome) has been mapped and functionally characterized to a high degree.

The little skate’s genome map will be “a huge resource for understanding human evolution and our vertebrate ancestry,” Nakamura said. Sharks and skates are ancient creatures that sit near the very base of the vertebrate lineage on the evolutionary tree. They are much more similar to humans than are zebrafish, which, despite being a common model organism in biomedical research, sit on a more divergent branch of the tree of life.

“Having the skate genome will open a lot of new research questions in evolutionary and developmental (evo-devo) biology, and people will come to MBL to answer them,” Gómez-Skarmeta said.

The Marine Resources Center at the MBL is the one of the only places in the world that collects this species of skate and breeds them for study, primarily for evo-devo biologists. These scientists compare how embryonic development is genetically regulated across many animal species, looking for the emergence of novel features, such as fins evolving into animal limbs.

What makes this quest so challenging is the fact that “most animals are constructed with the same toolkit of genes,” Gómez-Skarmeta explained. Among vertebrates, for instance, only 2 to 3 percent of the genome is protein-coding genes, and those genes are essentially the same in fish, mouse and human. Somewhere in the rest of the animal’s genome, sometimes called the “dark matter,” are the instructions for how those genes will function, and these instructions will be very different across species.

“The way different life forms are generated—why a fish doesn’t look like a human—is by using the same genes in different ways. These is done by regulatory elements in the genome that turn genes on or off during the life of the animal,” Gómez-Skarmeta said. “To a great extent, evolution is the history of changing the regulation of gene expression during development.”

It’s no accident Gómez-Skarmeta, an expert in finding regulatory elements (also called enhancers) in the dark corners of a genome, and Nakamura, a developmental biologist, share a bustling Whitman Center lab. Their collaboration was first orchestrated in 2015 by Neil Shubin, the Robert R. Bensley Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago and current interim co-director of the MBL. Shubin studies the evolutionary origin of vertebrate features, especially appendages such as fins and hands. In 2004, Shubin and colleagues startled the scientific world when they unearthed a 375-million-year-old fossil in arctic Canada that had features of both fish and amphibians: a fish with limbs. This rare find of a transitional fossil, from the time when marine organisms first ventured onto land, would later become widely known through Shubin’s book, “Your Inner Fish,” and a PBS television series with the same name.

Nakamura was a postdoctoral researcher in Shubin’s lab when they realized that one path for exploring the genetic origins of innovation in fins and in paired appendages would be to find out what controls fin formation in the odd-looking little skate.

“The skate is really unique. Its pectoral fins are super wide,” Nakamura said. “In humans, if the hand develops too wide and it has 5 or 6 fingers, it’s a serious disease. So, we thought, if we could identify what genes regulate the formation of this super-wide fin in the little skate, it would help us understand [the generation of diversity] in an ancestral vertebrate and also a human disease.”

Shubin sent Nakamura to the MBL Whitman Center to work with skate embryos. That year, they pinpointed several genes in the little skate that also exist in limbed animals, but function differently. These genes, they suspected, generate the unusually wide pectoral fin.

Now the team is sequencing the entire little skate genome at several genomic centers across the world. In parallel, Gómez-Skarmeta is looking for the regulatory elements that fine-tune expression of their target skate fin genes.

The MBL, they agree, is essential to their work. “This Marine Resources Center is the best in the world,” Nakamura said. “We would never be able to breed this kind of huge marine organism somewhere else.”

Since Nakamura is based in New Jersey and Gómez-Skarmeta in Spain, they also appreciate the MBL as a place for “community, collaboration, discussion. Not only among skate researchers, but you meet a lot of scientists here working on many different species,” Nakamura said. “We can share techniques, we can talk about morphological or molecular diversity together. It’s just a really amazing place.”

—This story first appeared on appeared on the MBL website.