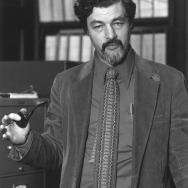

Prof. Emeritus Hellmut Fritzsche spent his career exploring semiconductors—materials that are the foundation of modern electronics. In particular, the experimental physicist became one of the world’s foremost experts on amorphous semiconductors, working with inventor Stan Ovshinsky to turn these materials into technology that would define the late 20th century—TV displays, computer memory and solar panels.

A member of the UChicago faculty for nearly 40 years and a former chairman of the Department of Physics, Fritzsche died June 17 at age 91. Colleagues remembered Fritzsche’s passion and energy, his intellectual generosity and his inventiveness in the laboratory.

“He was a very clever experimentalist. He took enormous pride in being able to solve experimental problems ingeniously,” said Thomas Rosenbaum, president of California Institute of Technology and a former colleague in UChicago’s Department of Physics. “You’d go to his lab and see things he built which were very simple but could do very complicated measurements. He had that touch.”

The Louis Block Professor Emeritus in Physics, Fritzsche was recruited to UChicago in 1957 after fixing the car of a stranded motorist who turned out to be with the UChicago physics faculty, said Morrel Cohen, a distinguished scientist at Rutgers University and senior chemist at Princeton University who worked with Fritzsche at UChicago for more than 20 years.

Early in his career, Fritzsche was recommended by Nobel-winning physicist John Bardeen to serve as his stand-in to investigate the claims of then-unknown inventor Ovshinsky, who claimed to have discovered useful electronic effects in materials with very disordered structures. Until then, it was thought such effects needed a rigid crystalline structure.

When the professor went to investigate, “he simply kicked Stan out of the laboratory and told him he would experiment with the materials on his own,” Cohen said. “When Hellmut finally came out, he said, ‘It’s real.’”

The finding would be one of the top physics discoveries of the decade, and because amorphous semiconductors are much easier to manufacture in wide-area formats than crystalline versions, they would point a way to a number of technologies, from solar cells to flat-screen displays. (“TV May Become Glass Sheet on Wall,” predicted a short 1968 article in the Milwaukee Journal in which Fritzsche was quoted.)

Fritzsche worked with the inventor to scientifically explain the behavior, and served as a consultant for Ovshinsky’s company Energy Conversion Devices as it expanded into solar cells, memory and electronics.

“He did an outstanding job of sorting out the physics that was going on in these semiconductors, which was important technologically but also to our deeper fundamental understanding of condensed matter physics,” Cohen said.

Passionate about physics and arts

Fritzsche served three terms as chair of UChicago’s Department of Physics, from 1977 to 1986. Later in his tenure, he oversaw the design and construction of the Kersten Physics Teaching Center building, which now serves as the primary facility for undergraduate and graduate physics education on campus.

“He spent enormous amounts of time on its design, which was indicative of his total immersion in what he cared about, but also his broad exposure to arts, literature, architecture and history—in addition to being a very good physicist,” Rosenbaum said.

Among other honors, he received the Alexander von Humboldt Award and the Oliver E. Buckley Condensed Matter Physics Prize and was a fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Association of the Advancement of Science. He also served for 16 years on the board of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Fritzsche’s wife Sybille Fritzsche, JD’68, was a prominent civil rights lawyer who served as executive director of the Chicago Lawyers Committee for Equal Rights under Law. She died on June 17.

Both were passionate about the arts; Fritzsche played for many years as an amateur violinist in such productions as Chicago’s annual “Do-it-Yourself Messiah” production of Handel’s Messiah, and both were members of the Early Music Society, the Tucson Museum of Art and the Contemporary Art Society in Tucson, Arizona, where they lived after retiring.

Hellmut and Sybille are survived by four children and eight grandchildren.