At first glance, you may see a serene lake at sunset or delicate petals on a winter-blooming tree. But look closer at UChicago professor of chemistry Bozhi Tian’s artwork and you might notice these images don’t quite capture the world as it is. They meld scenes of nature with hints of technology, much as his research merges biological and synthetic systems.

A materials scientist who works with semiconductors for biomedical applications, Tian designs devices to stimulate or modulate parts of the anatomy, such as the heart and neurons. One project his lab has been working on for almost eight years is a solar powered pacemaker. The team is also exploring technology to influence microbes, including an edible material that could modulate the gut microbiome, potentially helping to treat gastrointestinal ailments like inflammatory bowel disease.

Tian’s research is inspired by the natural world: its shapes and textures and patterns. And that influence suffuses his artwork, often created in conjunction with his science: a riverscape with a nanowire forest, a neural cell framed as a snowcapped mountain. These are created digitally, but Tian has been painting and drawing since childhood.

Encouraged by his father, Tian started practicing calligraphy when he was 3. He branched out to painting at 6 and started experimenting with design software at 15 or 16, when his father bought him his first computer. (Around that time, he was falling in love with chemistry and devoting more attention to science.) He still enjoys making analog art but finds it time-consuming.

At Shanghai’s Fudan University, where Tian earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in chemistry, his devotion to art and to science began to coalesce. He joined a research lab that designed and synthesized porous materials—orderly and geometrically structured with nanoscale pore size. Such structures exist in nature but not at the same scale, Tian says. The 2D and 3D arrangements fascinated him. “It’s essentially an art piece,” he thought.

Both scientists and artists must be innovative and imaginative, says Tian, inspired in how they re-create their vision of the world. This multidimensional creativity is particularly evident in one of his lab’s new research directions, what he calls “synthetic reality.” The team is focusing on designing tissue-like materials, but not in the traditional tissue engineering sense (such as growing artificial organs or materials for direct medical use). “We’re thinking more broadly,” he says.

Imagine incorporating organic tissue into your surroundings—an idea that struck Tian on a recent visit to the intensive care unit of Comer Children’s Hospital to meet with a collaborator. There it occurred to him that premature babies have physical and emotional needs that would have been met by their mothers’ bodies, but they are treated inside what is basically a batting-lined box. Perhaps the team could create an environment like a womb.

“We don’t really need reality, as long as it feels like reality,” he says. “That should be enough.” Likewise, some stringed instruments traditionally use gut string, made from animal intestines, which produces a warmer sound than steel. But a synthetic gut-like tissue might produce an equally beautiful tone. Reality: inspired by nature but made in a lab.

Tian believes that combining science and design is good business—it sells innovation through communication. “It helps motivate people,” he says, “bringing us together through storytelling.” But he admits that creating art is also a sort of compromise. He finds illustration relaxing but sometimes feels guilty for neglecting his research. This way, he doesn’t have to choose.

Transformative stain

The opalescent swirls on silicon membranes, as seen here under an optical microscope, aren’t created by dyes or pigments. The color comes from a process called stain etching, which eats through the surface of the silicon, leaving holes that scatter light, creating colored “stains.” But the process does more than cast psychedelic patterns—it creates nanoporous material that functions like a solar cell. Normally solar cells need at least two layers of different material to work, but Tian’s single-layer method creates soft, flexible, and extremely small solar cells that can be used inside the body. A tiny optical fiber carries light from outside to power them. “This is transformative because without the etching, the material is almost useless,” says Tian. But after a simple engraving process, it can turn light into electricity and help a heart keep pace.

Bioelectronics on the rise

To represent interfaces where electronics and cells seamlessly integrate, Tian created this composite image, superimposing a photograph of a flexible bioelectronic device onto a Chicago harbor. Shown across the bottom half of the image, the device is itself a composite: a rolled sheet of engineered vascular tissue embedded with wires that might one day be able to measure proteins or other chemicals in blood. Tian used vertical elements—the foreground electrode grids and the background masts—to “imply an upward progression of the field of bioelectronics.” Always sensitive to color, Tian chose warm hues “to give a feeling of harmony and positivity,” noting that a harbor is a place of security and comfort. “While the background and the foreground show very distinct objects,” says Tian, their juxtaposition presents a shared spirituality.

Nano-neuro blossoms

Highlighting recent breakthroughs in neural sensing and modulation, and the potential for biomaterials to treat neurological disorders, Tian illustrated a plum blossom tree. Its branches are neuron dendrites—treelike protrusions that carry signals from other neurons—as seen under an optical microscope. Tian invoked traditional Chinese painting elements: diffuse outlines, a black and dark red color palette, and a red seal in the corner. China’s national flower, the plum blossom holds special meaning. The plant, which blooms in the winter, signifies perseverance. “That’s the key message I want to highlight for this image. This is a tough field,” says Tian, who is the only faculty member working in bioelectronic stimulation interfaces at the University of Chicago. “We need perseverance to actually push through.”

Nanowired bioelectrics

Semiconductor nanowires have played a significant role in Tian’s research since graduate school. In this landscape, every element represents a cellular or nanowire feature and “tells you how the entire nanowire bioelectronics field has evolved,” he says. The mountains are cells; the river is the extracellular matrix (a network of proteins and other molecules between cells); the bridge is an intercellular nanotube (a conduit between cells); the sun is an extracellular vesicle (a membrane-enclosed globule that aids in cellular communication). In the distance, the green trees represent early research, which focused mainly on straight wires. Downstream, branched shrubbery and zigzag logs indicate new nanowire geometries. The wire bent at about 60 degrees on the mountain face depicts a device that records information from inside a cell—part of Tian’s PhD research.

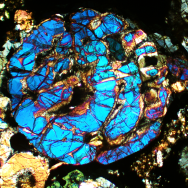

Engraved curvature

Tian’s lab creates 3D nanostructures using a classic printmaking technique: lithography. Using atomic gold as a lithographic mask, the team chemically etches silicon into complex shapes. Tian built this 3D reconstruction using a series of electron microscope pictures. The image shows only the surface of a skeleton-like silicon object, part of a material designed to adhere tightly to tissue. The colors highlight the difference in curvature: blue portions curve outward while gold dips inward. The original version used blue and red—a typical color palette for science—but Tian’s choice to replace red with gold points toward his humanistic impressions. “This etching, this engraving, seems like a very painful process for a material,” he says. It creates loss, but it’s also part of growth and reaching maturity. The etching process, to him, lets inner strength shine through.

Light excitement

Imagine a snowy mountaintop with a gondola cable straddling the peak, but on a nanoscopic scale. This scanning electron microscope image that accompanied an article published in winter 2018 shows a neuron with a silicon nanowire, which works like a solar cell, perched on top. When Tian shines a light on the wire, it converts photons into electric energy, stimulating—or exciting—the neuron. This technology can either activate or silence neurons and could help treat neurological brain conditions or restore vision to a damaged retina, for instance. Most methods for neural activation are either mechanically invasive or require genetic manipulation of target cells. Like the neurons they were studying, “we were extremely excited,” says Tian, to see the device work.

—Adapted from the Fall 2022 issue of UChicago Magazine.