More trees mean healthier neighborhoods, and a new map is helping the city of Chicago identify neighborhoods that could benefit from increased investment in street trees.

Health geographer and data scientist Marynia Kolak and a team of fellow University of Chicago researchers recently partnered with Chicago’s Department of Public Health to develop a new advanced mapping tool—one that combines tree data with other metrics related to health outcomes, including air quality, surface temperature and traffic volume.

That information will help shape the city’s plan to spend $46 million planting approximately 75,000 new trees over the next five years, focusing in part on census tracts with relatively lower numbers of trees.

Working as part of UChicago’s Healthy Regions + Policy Lab (HeRoP), Kolak and her colleagues found a relationship between these health factors and the amount of canopy cover—the extent to which tree crowns cover a neighborhood. More trees were associated with a range of positive outcomes, including better air quality and lower summer surface temperatures.

“The intersection of pollution and ‘greenness,’” can be complicated to navigate, said Kolak, assistant director for health informatics at UChicago’s Center for Spatial Data Science. Trees, however, are “a point of resonance and agreement.”

In addition to physical health benefits, trees are also associated with a role in boosting mental health. Many scholars have conducted research in this area, including Assoc. Prof. Marc Berman of the Department of Psychology.

But in Chicago, Kolak said, there are often fewer trees in historically redlined and segregated neighborhoods, as well as areas that experienced higher levels of past industrial activity. Those same areas tend to have higher levels of particulate air pollution and higher summer temperatures, which can negatively impact human health.

More pollution can correspond to a wide range of health disparities for people living in those neighborhoods, including higher rates of asthma. By overlaying these different categories of information, new insights can emerge that help officials address these challenges.

The city of Chicago recently passed a budget that allocated a total of $188 million in climate and environmental commitments—the most ever spent on the environment in Chicago. The tool will be used to identify areas that could benefit from increased canopy cover over the long term, as measured by three-dimensional LiDAR data.

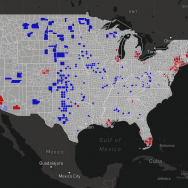

While there are plans to eventually make the city’s version of the tool available to the public, the HeRoP lab also created a free and open-source version to allow everyone to explore Chicago’s environment, allowing people to zoom in on their own neighborhoods to understand how they compare to nearby areas. Neighborhoods near the lake tend to be the coolest, while those near the interstate highways tend to be hotter and more congested with traffic. Dylan Halpern, a senior software engineer at HeRoP, co-led the development of the open-source tool with Kolak.

“The more you zoom in on a particular area, the more things are illuminated,” Kolak said. Because individual trees are visible as dots on the map, she noted, one can even see differences between what would seem to be similar developments, like shopping plazas, in different parts of the city. In some instances, affluent North Side shopping plazas still have more trees than South Side ones which are similarly designed.

The tool is also useful for conceptualizing specific projects: Some neighborhoods near the Dan Ryan Expressway, for example, have schools situated close to the highway, exposing kids to higher levels of air pollution in neighborhoods that are already densely populated, with lots of acreage of cement and asphalt.

While such areas could clearly benefit from more trees, the tool also reveals how some neighborhoods have maintained greenery despite facing historic inequalities. The Englewood neighborhood, for example, has a relatively high amount of tree canopy cover, which means that summer temperatures there are notably cooler than in neighboring areas which are a similar distance from the lake—a pattern that is visible in the tool’s map.

As the city of Chicago undertakes tree planting initiatives, it plans to do so in partnership with local communities, learning about concerns at a neighborhood level. Some community leaders have already discussed the need to assuage residents who negatively associate more trees with gentrification, and who could see tree-planting efforts as warning signs of unwelcome development.

Funding for the research tool pilot came in part from Bloomberg Philanthropies and was managed by the public health consultancy Vital Strategies as part of Healthy Cities, an initiative of the World Health Organization. To create the tool, the UChicago research team harmonized multiple datasets into a standardized format for evidence-based decision making.

Kolak, who specializes in studying the role of place in influencing social determinants of health, said that the tool makes clear that trees represent a convenient focal point for thinking about multiple issues in tandem going forward.

Better information, she said, can lead to more effective action: “This tool is an invitation to partnerships across different groups. It can highlight disparities, but then invite folks to the table for the next stage.”