If you think you know what a book is, turn back now. Elizabeth Frengel, UChicago curator of rare books, challenges you to put all your bookish assumptions aside and take a journey that spans the course of recorded history.

Frengel, an expert in book technology, is the curator of But Is It a Book?—the latest exhibition on display at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center. The exhibition breaks down classic elements of ‘bookness’ like format, shape and binding.

“I gravitate toward book objects that cause me to ask questions,” said Frengel. “So, building an exhibition around objects and books that really challenge, undermine and expand the idea of what a book is was really interesting to me.”

Those objects range from a clay tablet made in the 3rd century BCE to a modern audiobook. But are either of these books? It’s up to you to decide. The exhibition poses a series of questions: “Does a book need to have pages? Does a book need text?” Each decision sends visitors down a different path, a concept developed by exhibition designer Chelsea Kaufman.

“It’s easy to say, ‘I don’t know’ to these very meta questions,” said Kaufman. “But this choose-able path format breaks large questions down into manageable chunks. No matter what path you go down, you’ll find an example that proves and disproves your choice.”

Visitors will also be able to voice their opinions in an essay contest. Participants who submit a 100 word-essay that answers the question “What is a book?” will win a prize from Special Collections. The best entry will have the chance to be curator for a day.

Just like the exhibition, the following Q&A with Frengel reveals there are no easy answers when it comes to the nature of books. This interview has been edited and condensed.

What does a rare book curator do?

The duties of my job are to build the collections through gift and purchase. I am always trying to think, ‘What have we been drawing on historically? What are we missing examples of?’ I really want to help connect students, researchers and faculty with material objects in our collections; that's really important to me.

I think my purpose for being here is to always be thinking about how materiality and the medium shapes the message. Text in the abstract may seem like an immutable and unassailable idea. And yet, texts are often transformed by their material packaging.

Do you have an acquisition you’re particularly proud of?

In the exhibition is a 13th-century manuscript Bible, which is important because 13th-century Bibles are all in one volume and they set down the order of the books of the Bible. They were mostly copied in Paris but circulated widely through Europe and became the Bible as we know it today. We didn't have an example and acquired in December a beautiful Vulgate Bible copied in Spain, a purchase that was made possible from a generous gift of two alumni.

So, what is a book?

A book is such a familiar object in our culture. You think, ‘I know a book when I see a book. I know what a book is.’ But then when you start thinking about it, we have a facsimile in the exhibition. Is a facsimile of a book a book or does it only count if it's the original object? Can a book have more than one function? In the simplest sense, a book records and conveys information. But can it do other things? Can it fail at conveying information? I think that it can.

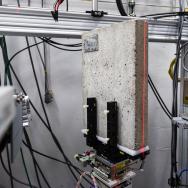

One of my favorite objects in the show is Wolf Vostell’s “Concrete Book.” When Vostell came to Chicago in the 70s, he confounded the function of everyday objects by encasing them in concrete. He wanted to complicate and undermine the utility of common objects and thereby make you think about how those objects work.

Why would he make a book out of concrete? It's quite possible that because concrete is so acidic and porous that it just consumed the text. Instead of the binding being this thing that allows you to open the pages and read it, his concrete book actually does the opposite; it destroys the text that it contains, which for a librarian is tough. But it is also a beautiful statement.

Does a book need to have text?

Vasilisa and the Witch’s Fire is one of my favorite objects in the exhibition. It's made by Joanna Robson, a Scottish book artist who does these amazing laser cut, silhouette books. On the surface, it appears to be a typical codex book, but it unfolds into a cube.

It tells the story, without text, of Vasilisa and Baba Yaga. Because it's a cube, you don't know where the story ends, and where it begins. But also, it's a classic Russian fairy tale. Fairy tales have been adapted through so many cultures, and in so many forms, beginning with oral tradition. Though this doesn't look like a book, in my mind it is strongly a book.

Are there objects in the exhibition you don’t consider books?

There's one object that is technically not a book, in my opinion. It's called “The Characters of Charles Dickens, a Very Interesting Game.” It takes the characters from many of his novels, and it's like whist or rummy. To take a trick, you have to match up and collect all four characters from “Bleak House” or “Little Dorrit” or “Oliver Twist.” I don't think it's a book even though there's text and characters and a story.

What’s on your nightstand these days?

I’m currently listening to Lucy Worsley's biography “Agatha Christie: An Elusive Woman.” I'm rereading “The Secret History” by Donna Tartt. I have lots on my TBR pile. My Christmas present to myself was Murakami's “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle.” I want to read Stanley Lombardo's translation of “The Odyssey.” I had not heard of Stanley Lombardo until I came to the University of Chicago. I went to get it from the library and as I was walking down the stairs to check it out, I started reading. The language is so immediate; that's definitely on my list.

—See “But Is It a Book” on display at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center until April 28 or view the web exhibit.