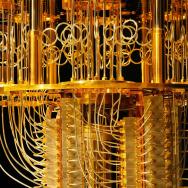

Quantum science holds promise for many technological applications, such as building hacker-proof communication networks or quantum computers that could help discover new drugs. These applications require a quantum version of a computer bit, known as a “qubit,” that stores quantum information.

But researchers are still grappling with how to easily read the information held in these qubits, and struggle with the short memory time, or “coherence,” of qubits, which is usually limited to microseconds or milliseconds.

A team of researchers at the University of Chicago have achieved two major breakthroughs to overcome these common challenges for quantum systems: They were able to read out their qubit on demand, and then keep the quantum state intact for over five seconds—a new record for this class of devices. Additionally, the researchers’ qubits are made from an easy-to-use material called silicon carbide, which is widely found in lightbulbs, electric vehicles, and high-voltage electronics.

“It’s uncommon to have quantum information preserved on these human timescales,” said David Awschalom, the Liew Family Professor in Molecular Engineering and Physics, senior scientist at Argonne National Laboratory and principal investigator of the project. “Five seconds is long enough to send a light-speed signal to the moon and back. That’s powerful if you’re thinking about transmitting information from a qubit to someone via light. That light will still correctly reflect the qubit state even after it has circled the earth almost 40 times—paving the way to make a distributed quantum internet.”

By creating a qubit system that can be made in common electronics, the researchers hope to open a new avenue for quantum innovation using a technology that is both scalable and cost-effective.

“This essentially brings silicon carbide to the forefront as a quantum communication platform,” said graduate student Elena Glen, co-first author on the paper. “This is exciting because it’s easy to scale up, since we already know how to make useful devices with this material.”

The findings were published Feb. 2 in the journal Science Advances.

‘10,000 times more signal’

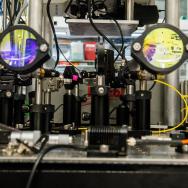

The first breakthrough for the researchers was to make the silicon carbide qubits easier to read.

Every computer needs a way to read information encoded into its bits. For semiconductor qubits like the ones measured by the team, the typical readout method is to address the qubits with lasers and measure the light emitted back out. This procedure is challenging, however, because it requires detecting single particles of light called photons very efficiently.

Instead, the researchers used carefully designed laser pulses to add a single electron to their qubit depending on its initial quantum state, either 0 or 1. Then the qubit is read out in the same way as before—with a laser. “Only now, the emitted light reflects the absence or presence of the electron, and with almost 10,000 times more signal,” said Elena Glen, a co-first author on the paper. “By converting our fragile quantum state into stable electronic charges, we can measure our state much, much more easily.

“With this signal boost, we can get a reliable answer every time we check what state the qubit is in,” Glen explained. “This type of measurement is called ‘single-shot readout,’ and with it, we can unlock a lot of useful quantum technologies.”

Armed with the single-shot readout method, the scientists could focus on making their quantum states last as long as possible—a notorious challenge for quantum technologies, because qubits easily lose their information due to noise in their environment.

The researchers grew highly purified samples of silicon carbide that reduced the background noise that tends to interfere with their qubit functioning. Then, by applying a series of microwave pulses to the qubit, they extended the amount of time that their qubits preserved their quantum information, a concept referred to as “coherence.”

“These pulses decouple the qubit from noise sources and errors by rapidly flipping the quantum state,” said Chris Anderson, PhD’20, co-first author on the paper. “Each pulse is like hitting the undo button on our qubit, erasing any error that may have happened between pulses.”

The researchers think that even longer coherences should be possible. Extending coherence time has significant ramifications, such as how complex an operation a future quantum computer can handle, or how small a signal quantum sensors can detect. “For example, this new record time means we can perform over 100 million quantum operations before our state gets scrambled,” said Anderson.

The scientists see multiple potential applications for the techniques they developed. “The ability to perform single-shot readout unlocks a new opportunity: using the light emitted from silicon carbide qubits to help develop a future quantum internet,” said Glen. “Essential operations such as quantum entanglement, where the quantum state of one qubit can be known by reading out the state of another, are now in the cards for silicon carbide-based systems.”

“We’ve essentially made a translator to convert from quantum states to the realm of electrons, which are the language of classical electronics, like what’s in your smartphone,” said Anderson. “We want to create a new generation of devices that are sensitive to single electrons, but that also host quantum states. Silicon carbide can do both, and that’s why we think it really shines.”

The research used resources of the UChicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, the Pritzker Nanofabrication Facility, and the Research Computing Center.

Citation: “Five-second coherence of a single spin with single-shot readout in silicon 4 carbide.” Anderson et al, Science Advances, Feb 2.

Funding: National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy, Boeing, Swedish Research Council, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, European Commission, Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

—Writing contributed by Elena Glen, Chris Anderson and Louise Lerner.