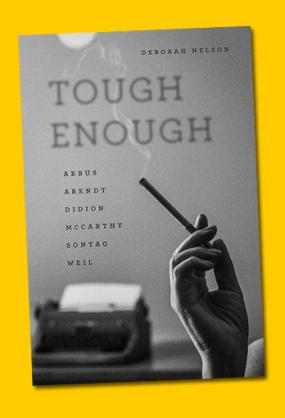

The University of Chicago Press has awarded the Gordon J. Laing Prize to Prof. Deborah Nelson for Tough Enough, her exploration of how six women faced pain with unsentimentality—and her argument for it as an alternative response to empathy or irony.

The Laing Prize is the Press’ top honor, presented to the UChicago faculty author, editor or translator of a book published in the previous three years that brings the Press the greatest distinction. The Helen B. and Frank L. Sulzberger Professor of English and the College, Nelson received the prestigious award, given since 1963, at an April 25 campus ceremony.

In Tough Enough, she traces the work of Diane Arbus, Hannah Arendt, Joan Didion, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag and Simone Weil—writers, critics and artists whose paths didn’t always intersect, but who all looked at “painful reality with directness and clarity and without consolation or compensation.”

For Nelson, that unsentimental approach not only shaped 20th-century culture, but remains relevant today in the face of specters like climate change, gun violence and racial prejudice.

“The problem is not that we do not know what is happening, but that we cannot bear to be changed by knowledge,” she writes in her introduction to Tough Enough. “The women I discuss in the following pages all insist that we should be changed, however much we give up in the process.”

Nelson—who chairs the Department of English and specializes in the study of late 20th-century U.S. culture and politics—spoke recently about her book and the audience she hopes to reach.

Tough Enough has already been well received, winning the Modern Language Association’s Lowell Prize. What meaning does the Laing Prize hold for you?

This is in the community of people that I've been working with for 23 years. These are all my friends. These are all people that have helped me become a scholar and writer—some by reading draft after draft of this book. It's more fun in that way. It’s sort of “in the family.”

If you look at the former Laing Prize winners, that's very august company. It's a great honor. And if you look at how few women have won, I think I'm the fourth woman to win this award in 56 years. That’s even rarer company. It’s exciting, and it’s fun to celebrate with friends and colleagues.

The book was published in 2017, but the project spanned for nearly a decade before that. Why did you want to write it?

The book really started when my mother was very ill, and her suffering was quite extreme. I was very interested in the problem of suffering and how you stay in a relationship when you can’t do anything about it. I thought, to some degree, Diane Arbus is OK with being helpless in front of other people's pain. You can still stay in its company. That was a really useful idea to me: How can you not be so disappointed by your helplessness that you leave the scene of suffering, when your presence might be all that matters? I don’t think I realized that until two years later, but it was very wrapped up in a personal dilemma of mine. And Arbus seemed to provide a way to think about it.

How did you select these six women in particular as your subjects?

There were some strong connections here, which made it a more coherent book. Simone Weil sort of stands alone, although she was certainly in Paris when Hannah Arendt was. Mary McCarthy and Hannah Arendt were very close friends and worked together on a lot of things. Susan Sontag was of a different generation, but shared some of the same preoccupations and milieu. Some of the questions Sontag raised about Diane Arbus’ work have been very compelling to generations of critics, so they were kind of a natural pair. And Joan Didion's been called the Arbus of journalism. She sort of flowed from Arbus in terms of a certain relationship to the objects of observation—in their pitiless, or unsentimental view of the people they write about or photograph.

I always back my way into a project. I'm more of an inductive thinker. I start to get interested in something, and I start to see the patterns and where they go. The patterns seem to be very vivid in certain places, but in others, it's not as distinct and not as interesting. For a long time, I didn’t know what I was writing about. But I was confident I would know, at some point.

What was the audience you wanted to reach?

What was in my mind was: “How would you write this so that an undergraduate could read what you’re writing?” Because they're smart, they're curious, but they won't know what you know. So how do you titrate the information, the background, the context and the ideas in such a way that it's more accessible to a broader range of readers?

Students could be a proxy for a kind of educated audience that is interested in the work of these women—or interested in problems of empathy and suffering. These women are well-known enough that I’d also like the book to be useful to their readers, to prompt them to think about the work in a new way. Reaching a broader, non-academic readership—that’s something you hope happens, but you can never know if it’s going to happen. That’s a bit of luck.