Editor’s note: This story is part of ‘Meet a UChicagoan,’ a regular series focusing on the people who make UChicago a distinct intellectual community. Read about the others here.

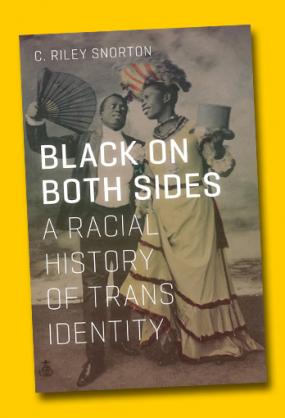

Two black performers stand together, one in a tuxedo and the other in a flowing dress—their sex and gender uncertain. In choosing this century-old French postcard as the cover of his latest book, Prof. C. Riley Snorton wants to send a message: Trans identity is not new.

“If we look historically, we’re not only charting the lives of those who have existed in the past,” Snorton said. “We can also learn about what they were doing, and honor their lives and the survival strategies they employed.

“Our time is not so unique that we can’t learn from other times.”

A black and transgender cultural theorist who joined the University of Chicago faculty in 2018, Snorton belongs to the very communities he studies. His research draws from black studies, queer theory and trans theory—seeking to complicate and expand those histories through the creation of a new vocabulary.

Teaching a class of undergraduates one recent morning, Snorton led a discussion about intersectionality. Coined by renowned legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, the term refers to how experiences of discrimination differ according to an individual’s intersecting identities, such as race and gender. To clarify the concept for his students, Snorton described it as “walking through a crosswalk, with cars coming at you from every direction.”

Snorton has devoted his own career to exploring these types of structural forces. His book Black on Both Sides, published in 2017, was the first to weave together the study of race and transgender identity, exploring those intersections from the 19th century to the present. It has won numerous awards, including the Modern Language Association’s Scarborough Prize, given annually to an outstanding scholarly study of African American literature or culture. The MLA’s selection committee described Snorton’s book as “essential reading” that created “new ways to imagine livable black trans worlds.”

The nearness between scholar and scholarship can help produce work that feels more complex and engaging. Snorton arrived at Columbia University as a queer teenager, but growing up in South Carolina had left him unfamiliar with transness. Reading philosopher Judith Butler introduced to him the concept of gender as a social construct—giving him “a launching point to do my own kind of exploration.” Performing as a drag king in college, he discovered himself as trans.

Snorton’s preface to Black on Both Sides mentions the life and death of Blake Brockington, who in 2014 became the first black trans homecoming king in North Carolina. He details how Brockington’s family saw his coming out as a “decision”—a reaction that felt close to Snorton’s own upbringing in the Bible Belt. Reflecting on Brockington’s 2015 death by suicide at age 18, Snorton also reveals his feeling of survivor’s guilt, sharpened in a world where so many trans people are attacked or killed.

He has since heard from friends of Brockington, who read his words as a moving remembrance.

“I think proximity sensitizes me differently as a reader,” Snorton said. “There’s a different way of writing that’s not about ‘translating’ native knowledge into general knowledge.”

Snorton, who teaches in the Department of English and the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, did not plan to write Black on Both Sides this soon. His first book, Nobody Is Supposed to Know, examines how negative perceptions of black sexuality are reinforced by media and pop culture portrayals of the “down low”—black men who have sex with men without identifying as gay, queer or bisexual. After publishing that in 2014, he initially wanted to write about the blues, and how sexuality in music informed how the public thinks about the Great Migration. He would write about black trans lives eventually.

A conversation with a mentor convinced Snorton it was time to start: In the midst of so much anti-trans violence, Black on Both Sides felt necessary to help archive black and trans identity—and to document strategies that might help others feel “more free.”

Still, he dismisses attempts to treat his scholarship as autobiography. Black and trans lives are also worthy of study by people without those lived experiences; Snorton simply offers a unique perspective. Distance does not move a writer closer to objectivity.

“The book is not a memoir,” Snorton said of Black on Both Sides. “I’ve had requests to come in and tell my story alongside the book. It’s a kind of a complicated, uncomfortable situation. I don’t think many people ask, say, a Shakespearean scholar to talk about the first time they’ve read Shakespeare as a way of setting up their research.”

Yet there is something personal woven into Snorton’s work, a celebration of black creativity and artistry. Both his books drew inspiration from black musicians: Black on Both Sides shares its name with the debut album of rapper Yasiin Bey (née Mos Def); Nobody Is Supposed to Know claimed its title from a line in “Creep,” the 1994 R&B single by TLC.

Those sorts of cultural influences are clear when you walk into Snorton’s apartment. One wall is covered with prints by black artists, including Jean-Michel Basquiat. Another is decorated with record covers: Tina Turner beside Bob Marley, Grace Jones next to Prince, Harry Belafonte and Stevie Wonder in opposite corners. The unifying theme? Black music in the diaspora.

Walk onto Snorton’s balcony, and you’ll get a sweeping southward view of Chicago—Soldier Field and Lake Michigan to the east, train tracks stretching across the neighborhood and out of sight. The city, he said, represented a place where he could feel “deeply related to black politics and black life.”

UChicago offered its own allure too. After teaching at Northwestern University and Cornell University, Snorton felt drawn to the “robust intellectual community” of the Hyde Park campus—one that facilitated collaboration not only with other scholars of trans studies, but with colleagues versed in black studies and black feminism.

“When you go somewhere and you’re not the only one who works in your field, it means you’re actually in a space of growth,” he said.

That allows Snorton more room to develop as a scholar and a teacher. His current syllabuses are filled with authors he has read for years, from Butler to Hortense Spillers to Sylvia Wynter. But after teaching students for nearly a decade, this fall marks the first time he has listed his own work.

“It’s awkward to assign your work, because you feel like you’re imposing yourself,” Snorton said. “But it’s also awkward not to assign your work, because maybe then your students don’t realize what’s at stake for you.”