In September 2020, Joanne Lee Molinaro, JD’04, jokingly told her followers, “You have to stop crying at my TikToks. Like, seriously, it’s just a cooking video.”

On TikTok for less than two months, she’d already become a viral sensation, largely because her posts are more than “just” cooking videos. In eloquent voiceovers, Molinaro invites viewers into her kitchen, her home, and her life. Whether she’s talking about her parents’ experiences emigrating from North Korea to South Korea, her own upbringing in America, or her personal philosophy, she is open, compassionate, and unapologetically opinionated—all while preparing vegan dishes, most of them updating the Korean cuisine she grew up with.

In one post that has 2.5 million views to date, she tells a story about her mother defending her from a fat-shaming woman in a store, while on video she makes a noodle dish called japchae. In another, she recounts her dad’s support of her divorce as she prepares a spicy tofu dish: nine million views. (She has since remarried; her husband, pianist Anthony Molinaro, is another frequent topic and occasional guest, and his music often accompanies the videos.)

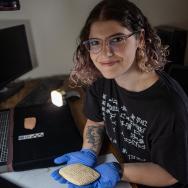

Soon Molinaro was more than a partner in a law firm with a fun side hustle. As the Korean Vegan, she introduced staples like gochujang, a spicy chili paste, and tteokbokki, chewy rice cakes, to both vegans and nonvegans whose knowledge of Korean food ended at kimchi and barbecue. Viewers familiar with the cuisine learned from her that jjajangmyun, a noodle dish with black bean sauce that happens to be Molinaro’s favorite, could be made without pork, and that gamjatang—literally, “potato stew”—could focus on the potatoes instead of the meat.

There’s no telling where Molinaro will venture with each new post. Her childhood, family, and running are frequent subjects, but she’s caused a stir with episodes about politics, racism, and disordered eating. The one (near) constant—whether she’s speaking as herself or in character as Gomoh, a Korean auntie—is food.

Molinaro’s three million TikTok followers helped make her 2021 cookbook—a collection of recipes and personal essays—a best seller. Both the New York Times and the New Yorker picked The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Reflections and Recipes from Omma’s Kitchen (Avery) as one of the year’s best cookbooks, with the latter calling the recipes “simultaneously personal and rooted in the practice of generations.” This summer, it even won a James Beard Award.

These days, being the Korean Vegan is a full-time job. Molinaro has a weekly newsletter, an online meal planner, and a second book in the works, and she promotes all three on social media and her website. Alongside all of that, she remains of counsel at Foley & Lardner LLP and teaches the occasional continuing legal education course.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Why law school

“I’m an adult and I don’t know what to do. Might as well go to law school.” But once I got to the University of Chicago I felt I had really made a great decision. I loved my professors. Loved my classmates. I loved everything about it.

Although my career choice of lawyer was not made with a great deal of intention, everything I did thereafter was very purposeful.

Eat, hate, love

I have this love-hate relationship with food where I love to eat; it makes me happy. I love eating jjajangmyun and French fries and all those things, but eating those things is at odds with the body that I have been conditioned to seek. And that conditioning is probably something I can no longer erase.

That’s one aspect of my relationship with food. We can also talk about how I hated Korean food until I went to college. I think that’s very common among second-generation Korean Americans and Asian Americans.

We never ate anything other than Korean food growing up, except for maybe birthdays. So I hated it. Then when I got to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, all the kids were eating Korean food.

Korean Vegan isn’t an oxymoron

Korea’s culinary evolution is as complicated and nuanced as every other country’s. It’s not straightforward.

One of the dangers of the popularity of Korea, as represented by BTS, by Parasite, and by Korean barbecue and gochujang, is there’s this risk—almost an inevitability—of flattening. All our music is BTS. All Korean food is barbecue and gochujang and bibimbap. And unfortunately, a lot of people assume, incorrectly, that Korean people don’t know how to do vegan.

There’s an argument that Korean food is the best for vegans. It’s delicious, and so much of it is already vegetable-centric.

What her parents think

When my parents went on the book tour with me and they saw the kind of impact I was having on my community, my father in particular was agog.

The art of conversation

When I started posting these TikToks, we had all been stuck in quarantine for a few months, and I felt like the world was blowing up. The irony is my husband and I had just moved into this beautiful home, and the whole purpose was to entertain. We had two dinner parties before we had to shut it all down.

The thinking was, I can’t do real-life dinner parties, so I’ll put these videos up. And when you go to a dinner party, yes, you enjoy the food. But your host isn’t regaling you with the details of how she created the food. You’re talking about what you did that day, an interesting thing I read in the news, or, oh, let me tell you this incredible story my mom told me.

Life in the comments section

In some respects, the avalanche of attention I started getting on TikTok was a blessing in disguise. If you’ve got 20,000 comments, you’re not going to be able to read the bad ones. Even if I did see the occasional negative comment, it just didn’t hit me in the way I expected it would.

“It’s delicious, and so much of it is already vegetable-centric.”

That started to change once my content became more political. During the election fraud accusations of November 2020, when I started posting more about my thoughts, it became much harder to ignore some of the negativity. Sometimes I would try my best and would be successful. Sometimes I would be totally unsuccessful, and it would ruin my day. And sometimes I would use it to create more content that went viral. [Molinaro’s November 8 video explaining the rules of civil procedure regarding fraud claims in the presidential election ultimately turned into a piece for the Atlantic.]

Vegan philosophy

The reason people have this notion of veganism as being elitist is because part of it is true. I’m very privileged that I get to make these ethical calls on my food, as opposed to having no money and just eating whatever I can get into my stomach, like my parents did.

When I went to Korea to do research for the book, I met with Jeong Kwan Sunim, a Korean Buddhist nun who does not eat animal products as part of her philosophy. She said, “I don’t call myself vegan. What the hell does vegan even mean?”

There’s a lot embedded in that word, for good or for bad. Part of what I’m trying to do is take that word and use it in a way that’s empowering as opposed to gatekeeping.

From The Korean Vegan Cookbook

by Joanne Lee Molinaro, JD’04

For Joanne Lee Molinaro, food and family are inseparably tangled up together. So in The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Reflections and Recipes from Omma’s Kitchen, the reflections loom as large as the recipes. In two short essays excerpted from the book, Molinaro recounts stories about her Omma (mother) and Appa (father).

Omma and sweet potatoes

After my mother’s family crossed the 38th parallel when my mother was about a year old, they landed in a small valley along the southern fringe of South Korea called Suk Bong Rhee, Chun La Namdo. They were referred to as “Korean War refugees.”

They were homeless. My grandparents traveled from house to house, begging for scraps of food and a place to sleep for the night. When they were lucky, they dug up leftover vegetables from recently harvested fields to supplement their daily meal of watery porridge.

Eventually, my grandfather was able to find a job as a janitor at a local middle school. He was good with his hands—he made kites for my mom and whittled toys for the neighborhood children. They were always poor, though.

Still, my mother remembers her childhood with great fondness. Poverty and war are powerful, yes. But so is the taste of fresh berries picked by your own hand along the ridge of a mountain lumbering over the hot months of summer like a drowsy silverback. Or the smell of barley heads snipped off their willowy bodies and roasted over an open flame beneath a blanket of preening stars. Her favorite, though, has always been sweet potatoes.

“You know, when I eat these sweet potatoes ...” My mother has a way of saying her words in English as if they are too big for her mouth. She cuts them up into small pieces—“poe-tae-toes.”

“... when I eat these sweet potatoes, it always makes me remember when I was a little girl,” she recounts one day while slicing up the bright orange yam I had just taken out of the toaster oven. My mother rarely comes by my house, but I am sick and she insisted on bringing me a vat of radish soup. To this day, my mother’s soup is my cure-all. As a nurse, it’s her way of showing affection and care (the word she often used instead of the awkward-sounding “love”).

“Why?”

“Because,” she starts, while holding out a gooey orange morsel. “Because,” she reiterates, “these were the best food.”

“What do you mean, the ‘best food’?” In my mind, the list of “best foods” included French fries, Chicago-style deep-dish pizza, donuts. It did not include sweet potatoes.

“When we were refugees ...” she answers between mouthfuls, expertly peeling the skin off another stringy piece, before popping it into her mouth.

“Wait. When you guys got to South Korea?” I ask. I realize that I actually know very little about my mother’s childhood. Other than the few snatches of conversation I managed to overhear over the years, most of what I “know” is nestled between Wikipedia and myth. This was the first I’d ever heard her talk about what it was like shortly after escaping North Korea.

“Mm-hmmm,” she says from inside another mouthful. “We had nothing. Nothing. So, the people in that village, they would harvest these,” holding up what remains of her potato in my face, “and then give us what they had left over. And we would eat them just like this,” she finishes, while sucking her fingers. And I believe her, more than I’ve ever believed anything else she’s ever said to me, because she isn’t looking at me when she explains these things. My 4-foot 11-inch, 90-pound mother is too busy cleaning her plate.

“And then, afterwards, I would run over to the field and dig up whatever I could find, you know, just a small piece,” then she shows me the underside of her hand, which has been her sign for “tiny” for as long as I can remember. “That was the way we lived back then.”

She pauses to look up at me.

“That’s why, when I retire, I want to serve. I want to serve that village. They were so good to us.”

Appa’s daughter

My father and I haven’t always had the easiest relationship. He is naturally aloof, and therefore affection—verbal or otherwise—is a bit like a foreign language to him. For most of my life, we got along by tacitly agreeing to stay out of each other’s way. It got to the point that just the sound of my father’s footsteps or his voice could cause me anxiety.

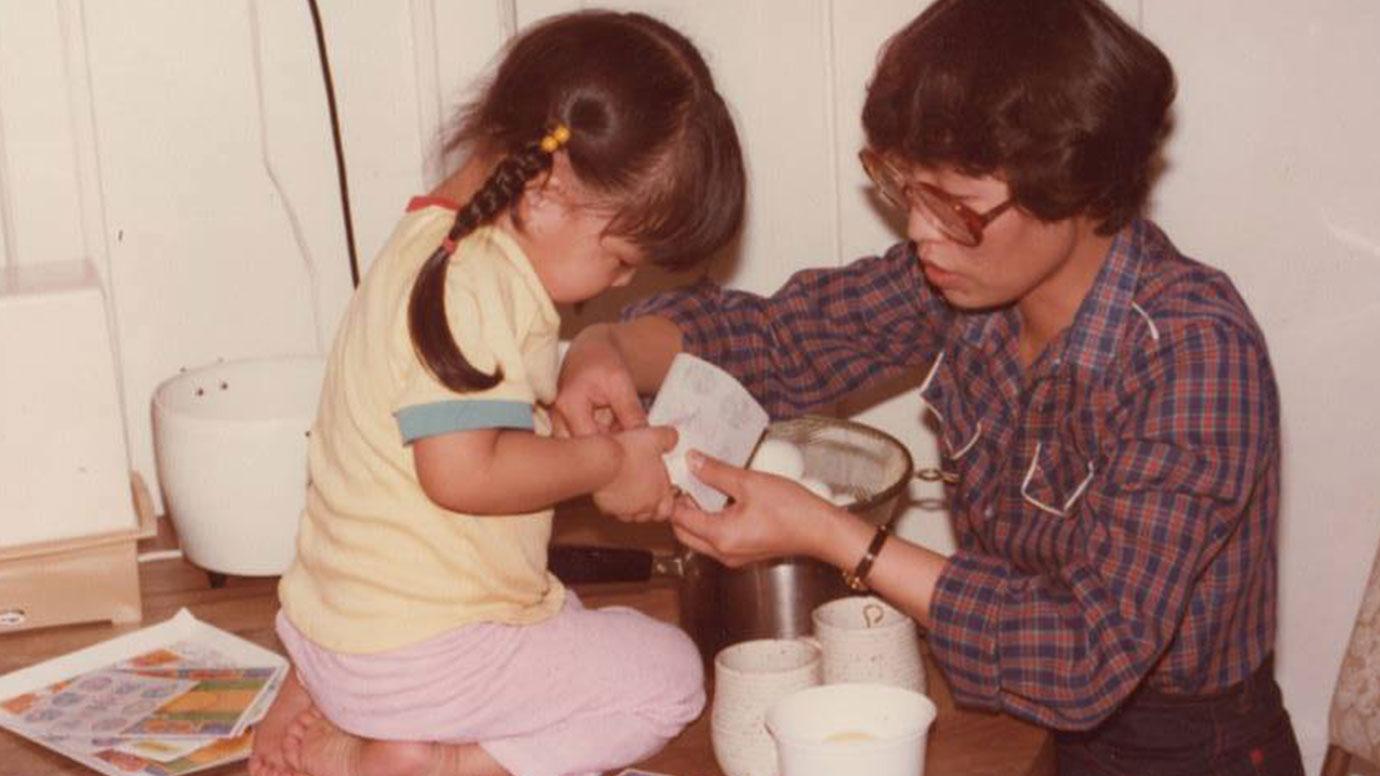

Being the first child of an immigrant also created a weird dynamic between us. As I began to speak English fluently, I quickly assumed the role of “translator.” At nine years old, I was the one calling and asking to speak with customer service, interacting with the store clerk at the cash register, or signing permission slips from school. At some point, before I was even a teenager, I witnessed how helpless my father seemed in the big American world, and as a result, I became the adult.

As my father grew older, I began to worry about how much time I had left to spend with him. I tried harder to find ways to hurdle the gap that had developed between us over the years. I never dreamed that running would be the thing that helped bring us together.

Despite a lifetime of hating running, in 2017, I signed up for my first marathon—the Chicago Marathon. My mother was in Korea, so she wasn’t able to cheer me on from the sidelines. My father, though, insisted on taking the 5:30 a.m. bus with a group of people he didn’t even know from a local Korean community organization, just so he could cheer for me at Mile 20. To be honest, I didn’t want him there. Without my mom there to take care of him, it would be up to me to make sure he was where he needed to be at the right time, and I already had twenty-six miles to worry about. I chatted with him on the phone the night before, hoping to dissuade him from coming.

“Daddy, are you sure you want to come? You really don’t need to ... I mean, it’s so early in the morning and it might get cold ...”

“Yah, I see you at Mile 20! Oh sure sure sure, I will be there! How long you think you going to take?”

I remember a lot of things from my first marathon: the fireflies stomping around my stomach while I waited for the starting pistol to pop off, my husband jogging with me through a bit of Chinatown before I waved him off in overheated delirium, and the handful of aspirins I downed at Mile 18 when the smooth Chicago pavement started to feel like shattered glass. But, my most memorable moment during the Chicago Marathon was at Mile 20. When I heard “Jo-ENNE!!” and saw my father’s face split into a smile that struck my ribs open with a gong. My seventy-two-year-old father with prostate cancer and a bad back tried his best to jog next to me, handed me the water bottle he had been holding in his hands since the crack of dawn, for nearly six hours, so that he wouldn’t miss this five-second window to pass it to me while asking, “Do you want me to run with you? Can I run with you?”

I left my father behind at Mile 20, wiping tears and sweat from my face, because in that moment, my dad, the one I’d spent my entire life protecting with my English-speaking shield, wanted to be and was stronger than his American daughter.

Three years later, I finally ceded to my father’s yearly invitations to join him for a family trip to Korea. We spent ten days trying to cram in two decades’ worth of visits I’d neglected to make. One day we decided to head to one of the nearby national parks, home to one of the most famous Buddhist temples and Buddhist monks.

We had driven hours to get to Naejangsan National Park and finally pulled into a large parking lot next to what appeared to be a sizable pond at the foot of a long and winding path that led up to the temple. We had packed some kimbap (Korean rolls) and tteok (rice cakes) left over from the feast we had had the night before, and we decided to refuel before climbing to the top of the sprawling hill.

Though my sister-in-law warned me that the kimbap we’d packed would no longer be tasty, they looked too inviting to pass up. I took one bite and instantly recalled that my sister-in-law is rarely wrong when it comes to food. Not wanting to waste it, though, I canvassed our little troupe to see who might eat my leftovers. Daddy stood at the edge of the pond, his left hand entwined in the strap of the camcorder I had bought him for this trip. A collar of happy trees, their boughs bright green and heavy with summer’s promise, supplied a shaded spot from which he could consider the dark reflections that shimmered on the surface.

Clutching the half-eaten kimbap, I skipped over to him. Giggling, and before he could say anything, I fit the small kimbap in his empty hand and skipped away, leaving a ribbon of pink laughter in my wake. He called after me, “What? I don’t want this!” But I just laughed harder, reveling in how perfectly the uneaten piece of food fit inside my father’s curved fingers, how colorful it looked against his walnut skin and beneath the cool eaves of the shifting trees, how I was spending the entire day with my dad in a place that made me feel more like his little girl than any place on Earth.

Text and photos excerpted from Korean Vegan Copyright © 2021 by Joanne Lee Molinaro. Published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

—This story was originally published by the University of Chicago Magazine