Editor’s note: This story is part of ‘Meet a UChicagoan,’ a regular series focusing on the people who make UChicago a distinct intellectual community. Read about the others here.

With more than a trillion tons of carbon dioxide now circulating in the atmosphere, and global temperatures projected to rise anywhere from 2 degrees to 9.7 degrees Fahrenheit in the next 80 years, switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy is a subject of critical attention. To make that switch, humanity will need entirely new methods for storing energy.

The current standard, lithium-ion batteries, rely on flammable electrolytes and can only be recharged about a thousand times before their capacity is dramatically reduced. Other potential successors have their own issues. Lithium metal batteries, for example, suffer from a short lifespan due to long needle-like deformities called dendrites that develop whenever electrons are shuttled between Li-metal batteries’ anode and cathode.

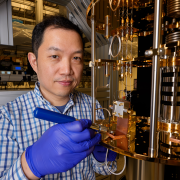

To Chibueze Amanchukwu, Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Molecular Engineering at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago, such thorny chemistry boils down to one flawed and often overlooked process—modern electrolyte design.

“The current approach to battery design, specifically with electrolytes, works like this: I want a new property, I look for a new molecule, and I mix it together and hope that it works,” said Amanchukwu. “But because battery chemistries are always changing, it becomes a nightmare to predict what new compound you should use out of the million possible options. We want to demystify the dark art of electrolyte design.”

Electrolytes are the third major component inside a battery—a specialized substance, often a liquid, that allows ions to travel from the anode to the cathode. To function, however, an electrolyte must exhibit a long list of very particular attributes, like proper ionic conductivity and oxidative stability, requirements that are made even more daunting by the millions of potential chemical combinations.

Amanchukwu and his team want to catalogue as many electrolyte components as possible, allowing any researcher to design, synthesize, and characterize a multifunctional electrolyte suited to their needs. They liken the approach to a popular construction toy.

“The beautiful thing about Legos, and the aspect we’re going to replicate, is the ability to build different structures out of individual pieces,” Amanchukwu said. “You can use the same 100 Lego pieces to build any number of structures because you know how each piece fits together—we want to do that with electrolytes.”

How to catalog a million components

Amanchukwu and his team use “natural language processing,” a type of machine learning program, to scrape data from scientific literature. Once a few promising compounds are found, researchers synthesize and test them with tools like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), a cousin of MRI, to better understand their properties and refine them even further.

Once tested, the compounds are put into actual batteries and studied again, and the resulting data is then fed back into the system.

The end result is a database of electrolyte components that can be easily combined depending on need. Such a system would dramatically accelerate new battery development, but its impact would be felt even beyond that.

Carbon capture technology currently relies on electrolytes in two ways. During the capture phase, an electrolyte acts as a solvent to help separate carbon dioxide from the air, and later a second electrolyte facilitates the C02’s conversation into a usable product like ethylene.

However, this process is energy-intensive. Amanchukwu believes that an electrolyte with the right attributes would be able to combine both steps, absorbing CO2 and converting it into a useful product at the same time.

A personal quest

His annual Battery Day teaches K-12 students about battery development through experiential lessons and art. It will also include coordinated workshops at Nigerian universities that cover subjects like “applying to graduate school” and “careers in energy.”

When asked what drives his outreach endeavors and his mission to transform electrolyte design, Amanchukwu explained that both subjects are close to home, first citing several natural disasters his family lived through in Texas and California.

“As someone from Nigeria,” he added, “I realized that any technology we make needs to be relevant to people back home so that we are all fighting to solve climate change problems and not leaving anyone behind.”

—Adapted from a story published on the PME website.