Editor’s note: This is part of a Summer Reading Series featuring notable books, author Q&As and more.

Patrice Rankine is a professor in the Department of Classics and the College and a writer. In addition to the reception of classics in current times, Rankine is interested in reading literature with insights from various theoretical approaches, including race and performance, queer theory and social history. His forthcoming book is “Theater and Crisis: Myth, Memory, and Racial Reckoning in America, 1964-2020.” The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Q: As a classics professor, how do you make the classics accessible and relevant for students?

Locating the classics might be like the game we play as children on summer road trips or long car rides: Find a red car. You might not normally notice red cars, but once they are raised to your awareness, they’re everywhere. The same goes for what we might call the relevance or accessibility of the classics. Once we realize that they are everywhere, we cannot unsee them.

I just finished drafting an article on alt-right or identitarian uses of the classics and the response of President Biden, who on the one-year anniversary of the events of Jan. 6, 2021, at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., called upon Clio, the classical muse of history. Biden, evidently standing near the 1819 sculpture of the Greek goddess that is in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall, grounds his message in what this statue represents to him, the stability of truth during unsettling times. Such uses of the classics occur across the political spectrum.

My point is this: The classics are everywhere; most of us are likely just not looking for them, any more than we are searching for red cars. In Chicago, Ceres, the Roman goddess of grain, stands on top of the Board of Trade building. In popular music, the Weeknd sits near a statue of the Three Graces in Las Vegas in the “Heartless” video. In my classes on classical reception in modern and contemporary society, my students find classical references across music, literature and theater, and video games, and inquire into their significance.

These modern and contemporary indices might spark an interest that leads to a deep study of the past. The classics have traditionally focused on Greek and Roman antiquity, seen as Europe’s ancestors, but increasingly we are also revisiting this past in new ways. A student just wrote me from his recent trip to Turkey, where he befriended some travelers from Kazakhstan. They asked him if he knew “Gerodot,” whom, as it turns out, is the author the student had just read with me in the spring term: Herodotus, the “father of history.” In that class, we discussed Herodotus’ understanding of the known world when he wrote his histories in the 5th century BCE. I had shared with the students my deep interest in Christopher Beckwith’s book, “The Scythians,” which is a history of a people Herodotus spends some time discussing. Beckwith argues that these Scythians, a nomadic people of the European steppes, influenced the Persians to the West and the Chinese to the East, establishing a flagship city in each region. For my student’s Kazakh friends, the Scythians are their ancestors.

These connections, ancient, modern and contemporary, make the classics relevant, accessible and exciting.

Q: What are you reading this summer?

I just finished reading Kwame Anthony Appiah’s “The Ethics of Identity” for the article I was writing on identitarian groups, national identity and antiquity. Appiah maintains that, as people, we are constantly negotiating our individuality in terms of personal morality and as ethics, asserting a selfhood woven from collective identifications, fabric we have been given by the past – history, ancestors, or racial, ethnic or gendered inheritance, and so on. Appiah leads me to the role of narrative in individuality and identity, and from there I find the classics to be replete with the material from which we craft these stories.

It is striking to me, for example, how widespread is the identification with Homer’s “Odyssey” among Black writers across the diaspora; or the persistence of Sparta’s band of 300 fighters at Thermopylae resisting the Persians – “Come and take it!” – among Confederates and contemporary identitarians. As a philosopher, Appiah does not spend a great deal of time on the narrative aspect of identity. I am more interested in this dimension of individuality, identity and its formation, as a classicist steeped in literature and myth.

I have also just begun reading Barbara Kingsolver’s “Demon Copperhead,” the story of a boy growing up in Appalachian Virginia to a mother entangled in the opioid epidemic. This novel, which won a Pulitzer Prize, is as hilarious as it is searching and, at times, harrowing. Kingsolver is a masterful writer. So far, I do not spot any red cars (no explicit classical references), but she riffs on Charles Dickens’ “David Copperfield.”

Q: In which bookstores in Hyde Park do you enjoy browsing?

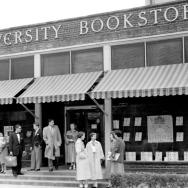

Because of the routes I take to and from where I live, I end up stopping at the Seminary Co-Op quite a bit. I love the atmosphere there, and the way that they lay out featured books on a great, big table means that I’m always sure to find something new or a book that I didn’t know about. Sometimes, if I’m feeling guilty about buying a new book that I might not be able to read immediately, I’ll just snap a picture of what’s on the table, for future reference.

I also love Powell’s as a Hyde Park staple. When I lived in Indiana, I’d sometimes drive up to Chicago for a day or so and binge on books there.

Q: What are you writing this summer?

I have a backlog of articles I’m working through and I’m also hoping to get back to a longer project that explores the role of enslaved people, across time and contexts, in the production of literary culture, titled “Slavery and the Book.” I have completed the article on identitarianism and national identity and another on the playwright August Wilson and his connection to Aristotle’s “Poetics.”

The article I am working on now brings me closer to “Slavery and the Book.” It is for a volume that looks at the role of enslaved people in every aspect of Roman literary culture, from writing letters and books for elite men, such as Cicero, to serving as copyists, bookbinders and librarians. Because enslaved people were a kind of invisible presence in Roman culture, the research takes a bit of sleuthing and learning to note what is said in passing or as an aside – sort of like finding red cars on that road trip.