The links between climate change and human health are becoming increasingly obvious: pollution, extreme weather events, food scarcity, pathogen spread.

Meet a few of the University of Chicago researchers who are tackling this monumental issue, one challenge at a time.

Targeting food insecurity with plant biology

Achieving tenure as a professor of chemistry at the University of Chicago gave Chuan He, PhD, the freedom to start something new.

“I decided to not just be a chemist,” he said. “And I started to think about what I could work on, and landed on RNA modifications. When we started in this field, there was very little research in this arena at the time, but recently the field has exploded because it turns out to be vital to all kinds of biological processes.”

In 2021, He and collaborators published a groundbreaking study showing that by inserting the FTO gene, which affects RNA modification, into rice, the plants grew three times more rice in the lab and 50% more rice in the field. The rice plants also grew longer roots, were better able to withstand stress from drought and photosynthesized more efficiently. Additional experiments in potato plants yielded similar results.

Now He is the director of the Pritzker Plant Biology Center, a new space to expand his RNA modification work and the research of other scientists searching for innovative ways to promote plant growth and resilience and increase crop yield.

“We’re considering many layers of pathways for modulating plant growth,” he said. “RNA modification is one aspect, but we’re also looking at temperature sensing because agriculture may have to move north as the climate warms, but northern regions will still be hit by extreme cold fronts, so we’ll need to develop plants that can resist the cold and grow fast. We also need crop plants that can better withstand warm weather. We could even modulate photosynthesis to increase biomass and yield.

“In the last several decades we’ve seen a huge amount of resources being put into human biology and health, and rightfully so,” He said. “But until now we have not paid enough attention to plant biology, and with climate change, this type of research is just as important.”

Wealth, race and health inequities

Elizabeth Tung, MD, assistant professor of medicine, focuses her research primarily on how race and wealth contribute to health inequities. The line to climate change may not be immediately obvious, but the relationship is there.

She points to a recent lettuce shortage. “Lettuce got more expensive because of issues related to climate change,” she said. “As the climate changes, who will be able to afford nutritious food, and what does that mean for the health of our communities? There’s a real connection there.”

She studies health disparities caused by social inequity, and wonders how they can be exacerbated by the pressures of climate change.

“We know that people with lower income, who are experiencing racism or violence, have much higher allostatic load than those who are not facing the same stressors,” she said. “That chronic activation of stress responses can increase stress hormones like cortisol, and over time that can directly impact health. Chronic stress contributes to a host of health problems, including cardiovascular disease, which is the largest contributor to the racial mortality gap.”

Those with the fewest resources and who are the most vulnerable are disproportionately affected by climate change, in everything from the rising cost of food to a lack of secure shelter from extreme weather events to increased risk of exposure to pollution and infectious disease.

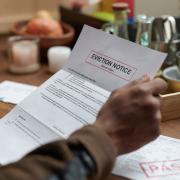

An area of particular focus for Tung is the intersection between violence and health inequity. “Violence is an outcome of inequity,” she said. “More than medical and mental health care, patients who are affected by violent injury will often say they need access to economic and legal resources. For example, eviction can be equally or more toxic to a person than not being able to fully rehab an injured leg. The chronicity of stress related to housing instability has major downstream effects on people’s lives and wellbeing.”

Add to that the effects of climate change on housing, which have already exacerbated the affordable housing crisis and increased housing damage due to flooding and other natural disasters.

These climate challenges will not only exacerbate existing health inequities, but will increase the strain on an already struggling health-care system, making it ever more difficult for those most burdened by the effects of climate change to access the resources they need to survive it. The question isn’t so much whether these issues will get worse in the future, but rather, how to address it.

“There’s a big movement in the health sciences to place a greater emphasis on the social determinants of health, but this is an existential issue,” said Tung. “Most of the solutions currently available to us rely on addressing the specific needs of an individual person or patient, but they don’t provide opportunities for systemic change. If wealth inequality continues to worsen, it will become even more difficult to sustain the services that we are able to offer. It’s a never-ending cycle.”

Environmental exposures and our genes

When she arrived in Beijing as a new university student, Yu-Ying He, PhD, was struck by the contrast to the rural area where she grew up — and especially the amount of pollution in the air, a major issue during that time.

“It constantly made me think about how different environments can lead to differences in our health, even when we’re working with a very similar genome,” she said. “It made me wonder how the biology works when we’re exposed to certain chemicals or radiation or even biological factors, like a virus. These things can put an imprint on our bodies, but we don’t always know what the long-term effects will be.”

Her current research focus is on understanding of how exposure to UVB radiation and arsenic affect the role of RNA methylation in cancer development. She studies epitranscriptomics — the modifications made to RNA that affect how and which proteins are produced within our cells.

She sees a connection between her work and climate change because it all comes back to one thing: human decisions.

“Climate change and pollution are deeply connected,” He said. “The chemicals we make and release into the atmosphere are a huge contributor to climate change. Humans are very innovative. However, we humans also create these unexpected and unintended consequences, but because it takes years for the toxic response to appear, we don’t realize it right away.

Perhaps the most obvious connection between her work and climate change is one that has been mostly successfully addressed by policy change. Those who grew up in the 1990s likely remember learning about the “hole in the ozone layer,” caused by human use of chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons.

Ozone layer depletion allows more UVB rays to reach the planet’s surface, affecting everything from agriculture to marine ecosystems to cancer rates in humans. Thanks to international agreements reducing the use of chlorofluorocarbons in the 1980s, the ozone hole is slowly shrinking; but in the meantime, its effects still remain.

Zoonotic diseases and human/animal dynamics

Interviewing Cara Brook, PhD, can be a bit of a challenge. An assistant professor of ecology and evolution, she spends much of her time halfway around the world in Madagascar, where she studies viral dynamics in Old World fruit bats. In a post-COVID world, the public is more aware than ever that bats can host zoonotic diseases that can make the jump to humans. Brook says this is due to the uniqueness of the bat immune system.

“Bats are the only flying mammals, and flight is extremely metabolically costly. To evolve the ability to fly and mitigate this metabolic damage, bats had to evolve numerous unique anti-inflammatory properties that appear to also allow them to better tolerate viral infections without experiencing extreme disease,” she said. “As a result, we think that bat viruses have evolved traits, such as high replication rates, that are not harmful to the bats but cause massive pathology when they spillover to humans and other animals.”

Brook doesn’t necessarily consider herself a climate change researcher, but she does see the relationship between climate change and her work on understanding how viruses persist in bat populations and the dynamics of bat-to-bat transmission, particularly because of how climate change places stress on the animals.

“We see spikes in virus transmission during the winter season, which is when bats are experiencing a nutritional deficit,” she said. “These spikes might lead to increased risk of exposure for humans and, as a result, increased risk of a spillover. Climate can drive nutritional stress through a number of different factors, such as changing the flowering or fruiting times for food resources, and through extreme weather events that can destroy trees and eliminate fruit crops.”

The increased risk of bat-to-bat transmission occurs when more bats congregate at fewer food resources, putting more animals in the same location at the same time. Additionally, when bats are stressed, a cascade of responses including downregulated immunity and heightened viral shedding mean that the bats are more infectious than at other times of the year.

External factors that increase the stress placed on bats drive transmission rates even higher. Deforestation due to human activity and extreme weather events increase the risk of zoonotic spillover as humans and bats come into closer contact.

Part of the challenge in understanding how climate change can affect the spillover of zoonotic diseases is that the relationship can be very heterogeneous. Things like humidity, precipitation and temperature can all affect disease transmission, while extreme weather events can create unexpected environmental factors such as standing water.

“Disease responses are non-linear,” said Brook. “Different pathogens might respond to something like an elevated temperature in different ways. For example, the white nose fungus that has decimated North American bat populations tends to replicate better at lower temperatures, so those infections might improve for bats as things get warmer, whereas viruses tend to respond positively to increasing temperatures up to a point.”

—This story originally appeared on the University of Chicago Medicine website.