Asst. Prof. Rachel DeWoskin has visited Shanghai every summer for nearly a decade, walking along streets that more than 18,000 Jewish refugees once called home. Spanning roughly a square mile, those blocks were where they established schools and businesses, rebuilding their lives in one of the few cities that accepted World War II refugees without visas.

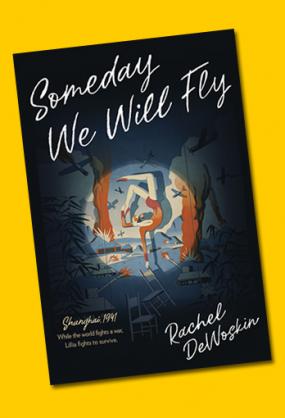

DeWoskin’s years of research culminated in the January publication of Someday We Will Fly, her fictionalized account of a young Jewish girl fleeing war-torn Poland. Described as “a beautifully nuanced exploration of culture and people,” the book is the fifth from DeWoskin—an award-winning novelist and assistant professor of practice in the arts who has taught at the University of Chicago since 2014.

In writing her novel, DeWoskin also relied in part on the family possessions of UChicago staff psychiatrist Jacqueline Pardo, whose German Jewish mother Karin Pardo (née Zacharias) lived in Shanghai as a child. A selection of those objects and photographs are on display on the third floor of Regenstein Library through March 24.

That exhibit is sponsored by the Joyce Z. and Jacob Greenberg Center for Jewish Studies, which is also supporting two events: a March 13 conversation between DeWoskin and former Secretary of the Treasury W. Michael Blumenthal followed by a concert of wartime music by Civitas Ensemble, and a March 14 symposium on the legacy of the Shanghai Jews.

DeWoskin spoke recently about her writing process, and what people can learn from this overlooked aspect of World War II history.

A display you saw in 2011 at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum planted the seeds for Someday We Will Fly. What was it that stuck with you?

There were two photographs in particular, of children who had escaped Nazi-occupied Europe and were living out World War II in Shanghai. The first was of a group of teenage boys, holding table tennis paddles and wearing matching polo shirts monogrammed with school insignias. The boys have the hollowed-out look of kids growing up in the context of war, but they also look like teenagers anywhere, mischievous and sweet.

I tried to imagine the lives of their parents, who had fled murder and persecution and brought their children to Shanghai, which had to be unimaginably unfamiliar and difficult for them. From there, they had built a school, created a table tennis team, and then gone to the trouble to make shirts. Those tiny insignias seemed to me iconic of the way human beings save each other and our children—not to mention the resilience refugees demonstrate, in ways both too small to be seen and too vast to be measured.

Next to that image was one of two toddlers holding rag dolls. The girls were in rags themselves, but someone who loved them—their parents, maybe, or friends or neighbors—had sewn dolls for them, and painted on those dolls lovely, expressive faces. The records of these children’s lives, and the objects that revealed their community’s devotion to them, inspired Lillia Kazka, the 16-year-old refugee at the center of Someday We Will Fly.

Lillia let me ask, in as many complicated ways as possible, the horrifying question of how human beings survive the chaos of war. Who loves us enough to keep us safe in the face of staggering danger and violence, and how can children come of age in circumstances as un-nurturing as those of occupied cities? How do we figure out how to live, to use languages both familiar and unfamiliar to tell stories that make our lives endurable? How do we hold on to the possibility of hope, even when we feel the constant pulse of dread?

Jacqueline Pardo and W. Michael Blumenthal were among the many people whose stories, books and lives helped shape your research and writing. How did the two of them inform your work?

I met Jacqueline Pardo by almost miraculous coincidence on campus. I went to her house in 2014 and was stunned to discover that she has a world-class archive of objects, documents and photographs that belonged to her mother in Shanghai during World War II.The objects, documents, and photos of Karin’s girlhood gave me the sweep and scope of a lived girlhood in Shanghai during the war: her school bag; notebooks and diaries; a thank you note she and her fellow Girl Guides wrote to American soldiers who had given them chocolate; and her exemplary report card, tarnished only by her music teacher’s hilarious note, “Can’t sing.”

I also talked with and read the books of the supremely generous Michael Blumenthal, a former Treasury secretary under President Jimmy Carter. Michael is a Shanghai Jew who grew up in the neighborhood of Hongkou, which in 1943 became a ghetto—all Jewish refugees were forced to move there. He gave me a view of China and humanity both profound and intricately detailed. He remembered the boys walking in circles around Hongkou, like teenage boys anywhere, hoping for the notice of their crushes.

He also described what it felt like to come to understand as a child that some adults rally in the face of hardship, while others disintegrate. While working in the White House, he asked himself of each powerful person he met: “How would he or she do in 1940s Shanghai, dressed in flour sacks?” His wonder and empathy informed and continue to inform mine.

Why did you also want to build an exhibit out of Jacqueline Pardo’s family possessions?

Whenever I find something astonishing or profound in the world, I want to show it to my students. This is why the Program in Creative Writing works so hard to bring our favorite writers and their brilliant work to campus, and why I was determined to have Blumenthal come and talk with us. When I saw Jacqueline’s mother’s belongings, and percolated how instrumental they had been to me in writing Someday We Will Fly, I wanted to show them to my students. I also assigned my writers to bring in objects, documents, and photographs that were parts of or necessary to their novels-in-progress.

Writers are doing research all the time. It’s not always formal, but all of our looking, asking, and listening—it counts. I wanted to say to my students how much their work in the world matters, that they’re creating a record so they can convey meaning or ask questions. We gain emotional and intellectual knowledge by looking at pictures or objects and asking: “How did this come to be?” Or looking at somebody’s mother’s book bag, report card, or paper dolls, and being transported by those objects into 1940s Shanghai.

Seeing one family’s record of wartime daily life gives us a way to wonder about how to help people who are now at risk, who are now separated, who are now fleeing violence and danger. I hope our exhibit elicits both empathy and activism.

Was there any part of the research process that surprised you?

What was surprising to me was the combination of the unbelievable difficulty families faced, and at the same time the normalcy a lot of them worked to achieve. As I’ve worked on the book, I’ve felt more and more that the world of 1940s Shanghai is maybe not that different from the contemporary world that we’re inhabiting right now. There are children facing the same sorts of risks as the kid at the center of my book. There are parents facing the same astronomical obstacles. There are people behaving heroically, and there are those behaving unforgivably.

If we look at history and imagine ourselves into it in ways both empathetic and literary, we can create ways to move toward a more socially just world.

Former Secretary of the Treasury W. Michael Blumenthal will speak with DeWoskin on March 13 at 5:30 p.m. in Fulton Hall, a conversation followed by a performance of wartime classical music from the Civitas Ensemble. On March 14, the Franke Institute will host a daylong symposium exploring the legacy of the Shanghai Jews through historical scholarship, literature and music.

DeWoskin will discuss Someday We Will Fly on May 1 at the Seminary Co-op Bookstore.