In a time when the world was changing fast for indigenous Hawaiians, Duke Kahanamoku was already becoming a legend.

Best known today as the father of modern surf culture, Kahanamoku entered the public eye as an Olympic champion swimmer and charismatic lifeguard. By the 1920s, a little more than two decades after Hawaii had been annexed by the United States, Kahanamoku was known far from the islands for his sleek athleticism.

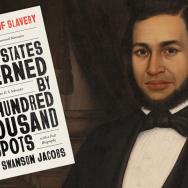

But his profile also attracted a more peculiar attention—and eventually became the focus of eugenicists. For his new book Capturing Kahanamoku, Assoc. Prof. Michael Rossi unearths the story of how leading anthropologists tried to square the surfer’s apparent “perfect” form with his being from an “uncivilized” race.

In Duke and his brother David Kahanamoku, scientists saw both a marvel and a mystery. But in their myopic focus, Rossi said, their inquiry completely “missed the biggest breakthrough from the Kahanamoku brothers: the invention of surf culture.”

“There's a question of what can we see with science—and what viewpoints are obscured,” said Rossi, a scholar of the history of medicine at the University of Chicago. “Part of the major fulcrum of the book is that these guys are popularizing surfing, but they're also talented musicians and they're hustlers,” he added. “Even as they’re are carving out a space in a really new world, trying to cope with the bustling economy of Hawaii in the 1920s, the scientists who are supposedly studying them in their entirety can only see them as ‘primitive’ people.’”

Rossi stumbled upon anthropologists’ obsession with the Kahanamoku brothers while working on a project about the blue whale model in the Museum of Natural History in New York City.

In going through the museum’s exhibitions archives—largely a process of flipping through people’s mail, Rossi says—he came across a note about sending a copy of a plaster cast of David Kahanamoku’s body to a museum at Yale University.

It was relatively unusual for individual people to be referred to in anthropological records of the time, Rossi says, which caught his attention. He learned that David was the brother of the famous surfer Duke, but questioned why someone would want his cast.

Years after finding the note, Rossi returned to the archives to piece a history together.

The note came from an era when Henry Fairfield Osborn, a paleontologist who later co-founded the American Eugenics Society, was the president of the American Museum of Natural History. In searching the museum’s archives, Rossi found a letter that briefly mentioned that Osborn received a surfing lesson from Duke Kahanamoku.

Osborn had visited Hawaii, after which he made an impromptu speech in San Francisco about how indigenous Hawaiians were dying at alarming rates because they held little resistance to imported diseases—in this case, the 1918 influenza pandemic.

He told his audience to prepare for the extinction of indigenous Hawaiians. But Osborn seemed captivated by Duke Kahanamoku, whose physical power seemed to gesture at the past greatness of the human form and maybe the future perfection of “civilized” humans.

In verifying the connections between the men, Rossi determined that Osborn’s time in Hawaii aligned with Duke Kahanamoku’s schedule, using dates in Osborn’s notebook and Hawaiian newspaper reports about the local celebrity’s appearances.

After his visit, Osborn asked a young physical anthropologist, Louis R. Sullivan, to conduct research on Hawaiians. Sullivan sent back meticulous, detailed reports, which Rossi was able to mine. He also pieced together much about Duke’s life via the Hawaii State Archives, which holds the surfer’s answers to fan mail and newspaper reports that mention him.

Spending as much time as he did with his subject’s letters—seeing their personalities and understanding how they were immersed in their own worlds—allowed Rossi to tell a story infused with humanity, rather than just an institutional history.

The story of Osborn and the Kahanamoku brothers is a parable, he said, “about how an overly narrow mode of inquiry—asking questions that give just one answer—can attenuate our sense of the greater moral world around us.”

“Science is a terrific tool and a powerful way of knowing about the world, but it works best when paired with philosophy, with art, with broader inquiry,” Rossi said.

The book comes around, in a sense, with Harry Lionel Shapiro, the scientist who took over Sullivan’s work at the American Museum after he died in 1925. After all his measurements and studies, Shapiro eventually put eugenics aside in favor of a more multicultural view.

“At the time, culture was seen as a ladder and most authorities assumed that you can't have multiple different kinds of cultures,” Rossi said. “The research program that started with Kahanamoku ends up producing the notion of culture that can accommodate different ways of being people.”