Retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, AB’41, says he cast just one vote on the high court that he would change now, if given the chance.

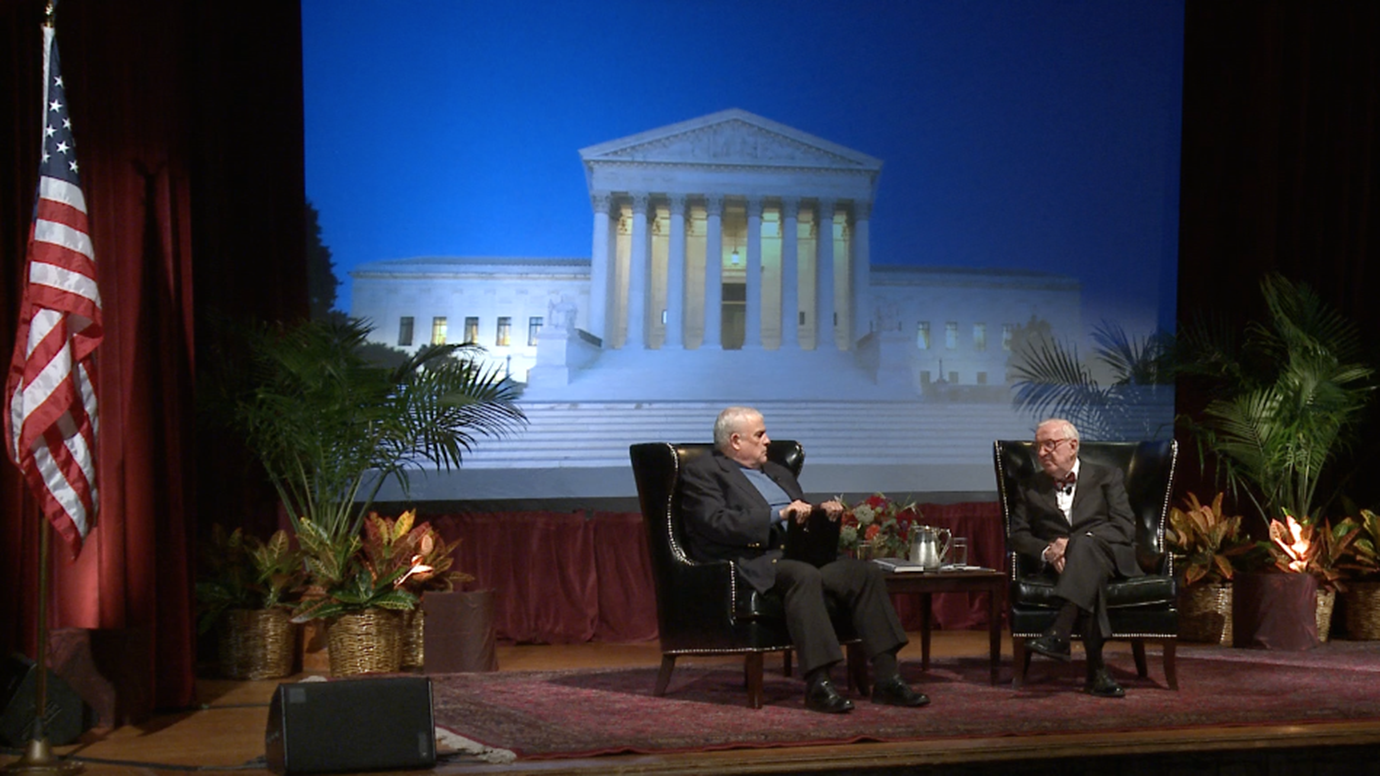

Speaking to a packed house Monday night at International House, Stevens, the third-longest-serving Justice in the history of the Supreme Court, said he regrets siding with the majority on Jurek v. Texas, the 1976 opinion that reinstated capital punishment in the United States.

Stevens, 91, explained his reservations in light of the recent execution of Troy Davis, a Georgia man convicted of killing a police officer in 1989. Davis was executed last month over the objections of civil rights groups, who argued that the recantations of key witnesses in the case warranted the commutation of Davis’ sentence.

“Even though [the case] met the evidentiary standards, there can’t help but be some doubts in a case of that kind,” Stevens said Monday night. The Davis execution “provides an example of one reason why the death penalty, as a matter of policy, is unwise if there is even a minimum of doubt.”

The College-sponsored event coincided with the launch of Stevens’ new Supreme Court memoir, Five Chiefs. Dennis Hutchinson, the William Rainey Harper Professor in the College and director of the College’s Law, Letters and Society, led a public discussion with the esteemed jurist that spanned topics ranging from gun control to judicial confirmation hearings.

Hutchinson is the author of The Man Who Once Was Whizzer White: A Portrait of Justice Byron H. White, and serves as co-editor of the Supreme Court Review, along with Law School Professors Geoffrey Stone and David Strauss.

The College’s Law, Letters and Society program co-sponsored the event, along with the office of University Communications and the Global Voices Lecture Series at International House.

Provost Thomas F. Rosenbaum introduced Stevens as “one of the most accomplished and respected alumni in the history of the College at the University of Chicago,” noting that Stevens grew up in Hyde Park, just around the corner from International House. “We are proud and honored to have Justice Stevens with us this evening,” Rosenbaum said.

The talk was Stevens’ first public visit to campus since 2002. He attended the Laboratory Schools at the University from kindergarten through high school, then studied English and was an active campus presence as a student in the College.

He had the unusual distinction of interacting with five different Chief Justices over the course of his legal career — experiences that are the focus of his new book.

Stevens has traced his preparation as a lawyer to his time at the College, where he studied writing with the novelist Norman Maclean, PhD’40, author of A River Runs Through It and other works.

On Monday, Stevens said he continues to revisit the Shakespeare canon, as well as the works by poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In response to a question, Stevens said the case that William Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him is “stronger than most people are willing to admit.”

One humorous exchange was when Stevens gave a novel reason for his opposition to the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. That decision limited the scope of campaign finance laws on the grounds that they can infringe on freedom of speech.

“It occurred to me that the Watergate break-in was financed with campaign expenditures,” Stevens said, laughing. “And I doubt that anyone would say the Watergate break-in … was protected by the First Amendment.”

“One would hope not,” Hutchinson replied, as the audience broke into laughter as well.

During the question-and-answer period, students from the College and the Law School sought anecdotes, wisdom and advice from the justice. The topics ranged from discrimination based on sexual orientation to whether he agreed with the late Justice William O. Douglas that “trees have standing” to be represented in lawsuits. (Stevens said trees do not.)

One aspiring lawyer posed the most pragmatic question of the evening, seeking Stevens’ advice on securing a Supreme Court clerkship.

Stevens answered him simply. “I look for brains, and somebody I’d like to work with.”