For Prof. Michael Kremer, innovation goes hand-in-hand with in-country partnerships that can save lives and improve livelihoods.

A Nobel-winning development economist who joined the University of Chicago in 2020, Kremer has already worked on interventions that have benefitted millions of people through better health, education and improved water quality.

Recently, he traveled to Kenya—where he has worked for decades—to meet with government officials and build some of those partnerships as he works toward the launch of new initiatives through UChicago’s Development Innovation Lab.

His current work in the country focuses on simple innovations that can yield significant benefits. One example is text messages offering advice for farmers: A recent study published in Science, which Kremer co-authored with Raissa Fabregas at UT Austin and Frank Schilbach at MIT, suggests that this increases the number of farmers adopting advice by a fifth, and increases agricultural yields by 4% at a very low cost.

“Since I taught in Kenya before graduate school, the partnerships we’ve made here have led to so much rewarding work on a range of issues, including deworming and public health. I look forward to working with my colleagues to address new challenges, from vaccinations to education,” said Kremer, the University Professor in Economics, the College and the Harris School of Public Policy.

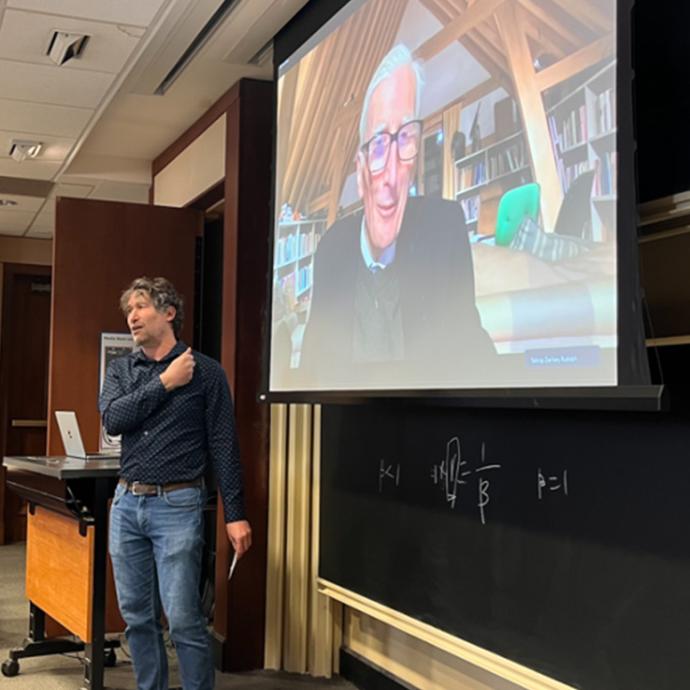

In 2019, Kremer won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with MIT’s Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo for work using field experiments to test interventions that reduce global poverty. He now serves as the faculty director for the Development Innovation Lab (DIL), which he started last fall to work with partners and use the tools of economics to identify, test, refine and scale development innovations.

Arthur Baker, the DIL’s associate director for research and planning, said collaborating with governments and other practitioners is one of the keys to creating successful solutions.

“Having close relationships with implementers and governments enables researchers to really understand the issues at hand, and how solutions might play out in practice” said Baker. “That partnership enables us to generate better solutions which can then be tested and refined.”

During his most recent trip to Kenya in July, Kremer met with a number of senior public officials in the Kenyan government, including Dr. Rashid Aman, the Chief Administrative Secretary of Kenya’s Ministry of Health, and Dr. Sara Ruto, the Chief Administrative Secretary of the Ministry of Education.

In both high-level meetings, Kremer shared research results and discussed future areas of partnership, noting that Kenya has been a torchbearer for evidence-based policy solutions. The government officials shared the policy and research priorities in the health and education sectors, and agreed to pursue opportunities of mutual interest that would build on identifying, testing, and scaling innovative solutions that would have a positive impact on the lives of Kenyans.

Kremer’s previous work in Kenya includes successful efforts to improve student health and educational outcomes by providing medicine that reduces infection by parasitic worms (“deworming”), and improving rural water quality through chlorination. Decades later, Kremer and his colleagues followed up with students who received deworming medicine and found positive impacts on their incomes as adults.

Now, he is examining new interventions that also have the potential to transform livelihoods—work that, as in his previous studies, relies in large part on partnerships with those on the ground who have knowledge of local issues.

In a recent episode of UChicago’s Big Brains podcast, Kremer said the prevalence of mobile phones in the developing world is creating new opportunities for innovative communication strategies.

“It’s possible to deliver information to farmers that is based on their location; tied to a particular time in the agricultural season; or timed around outbreaks of new pests,” he said. “So we did some trials of the impact of providing information to farmers, and found that it really did affect farmers’ behavior.”

Kremer notes that such solutions are not “magical” fixes to problems, but they can deliver real results: It’s cheap to send text messages, and if a few farmers use the information they contain to their advantage—for example, by applying lime to restore soil pH balance—the financial benefit can be ten times bigger than the cost of sending the texts in the first place.

This work is just one example of Kremer’s unique approach to innovation, which encompasses any change that can improve a system—including policy adjustments, communication strategies and technological advances. With Kenyan partners, Kremer is looking forward to developing and testing new innovations in agriculture, health and education through DIL.

“The combination of personal engagement on the ground with the intellectual rigor of research is producing very exciting work, both in terms of understanding the global landscape and in helping to provide practical solutions to problems facing people,” said Kremer.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He