Show Notes

When you think about corporate secrecy, nefarious shell companies and conspiratorial tax dodging, the state of Delaware probably doesn’t come to mind. We often think of exotic places like Panama or Bermuda, but the research of University of Chicago Adjunct Professor Hal Weitzman shows how it’s all happening right here in the United States.

In his new book, What’s The Matter With Delaware?, Weitzman goes down the complex Delaware rabbit hole to discover how this tiny U.S. state became the incorporation capital of the world—uncovering everything from criminal conspiracies to wealthy tax avoidance to political dark money.

Subscribe to Big Brains on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher and Spotify.

(Episode published June 9, 2022)

Related:

- Learn more about What’s The Matter With Delaware—Princeton University Press

- Hal Weitzman on What’s The Matter With Delaware?

- Delaware—The State Where Companies Can Vote—ProMarket

- UChicago event to examine corporations, secrecy and ethics—Chicago Booth

Transcript:

Paul Rand: When you think about corporate secrecy, nefarious shell companies, and even conspiratorial tax dodging, what comes to mind?

Hal Weitzman: You always think about a location like the British Virgin islands or Bermuda or Panama or Cyprus. These are very exotic, it’s almost like James Bond movie. It’s always happening over there, right? It’s never over here. It’s always over there. And what was interesting to me about Delaware is it’s very much here. It’s not over there. It is right here. And it sort of flies under the radar.

Paul Rand: Unless you live there you probably never think about the tiny state of Delaware, but University of Chicago Adjunct Professor Hal Weitzman says that’s a huge mistake.

Hal Weitzman: Most of us interact with Delaware companies at least once a day. If you think about Delaware companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Visa, MasterCard, or Walgreens or Walmart or CVS, I could go on and on and on, Delaware is the corporate air that we breathe.

Paul Rand: Now, wait a minute, you might be saying. Isn’t Amazon in Seattle? Isn’t Google in California? And isn’t Walmart in Arkansas? Well, it turns out that all of these companies are actually registered in Delaware.

Hal Weitzman: So this is a state that has fewer than a million residents. The populations about the size of Tucson or Grand Rapids metro area. But it has 1.6 million companies registered there, including two-thirds of the US’ biggest public companies and-

Paul Rand: The Fortune 500.

Hal Weitzman: Right. But also most public companies of any size are registered in Delaware.

Paul Rand: An average of 683 businesses register in Delaware, not a week or a month, but every day.

Hal Weitzman: Most of them are out of state companies. They have little more than an official registration in Delaware. They don’t do any real business there. They’re not located there. And the companies in Delaware are not just the ones that are located in other states, they’re located all around the world.

Paul Rand: The question is why? In his new book, What’s The Matter With Delaware?, Weitzman goes down the complex and, frankly, infuriating rabbit hole to discover everything from criminal conspiracies, to wealthy tax avoidance, to political dark money.

Hal Weitzman: Well, Delaware is everywhere. Delaware plays a critical role in the capitalist system. And it’s one that’s really largely unexplored, at least outside of scholarly journals.

Paul Rand: From the University of Chicago Podcast Network, this is Big Brains, a podcast about the pioneering research and the pivotal breakthroughs that are reshaping our world. On this episode, what’s the matter with Delaware, and how to fix it. I’m your host, Paul Rand.

Paul Rand: For people on the inside, Delaware is known as the corporate capital of the world, but the rest of us don’t pay much attention to the somewhat small state.

Hal Weitzman: Although I really like Delaware and I’ve visited there, very unglamorous place. Nobody would say, “Delaware’s on my bucket list.” You might remember this scene in Wayne’s World, where Wayne and Garth find themselves in front of a green screen that’s got Delaware and they have no idea what, anything. They have no association with Delaware whatsoever.

Mike Myers: Imagine being able to be magically whisked away to Delaware. Hi. I’m in Delaware.

Paul Rand: I want to congratulate you. That is the first Big Brains Wayne’s World reference we’ve ever had.

Hal Weitzman: Hopefully not the last, but there’s sort of like an everywhere USA type feel to Delaware. It’s kind of nondescript and could be anywhere. I said, Delaware’s everywhere. Delaware’s also anywhere.

Paul Rand: Yeah.

Hal Weitzman: I mean, it really could be anywhere. And so it’s a great front for conducting this very lucrative business.

Paul Rand: The first secret behind Delaware’s ability to attract businesses is how easy it makes the process to register.

Hal Weitzman: You and I, Paul, could go and form a Delaware company by the end of this podcast.

Paul Rand: For just $1,000, you can start a business in under an hour. For an extra $500, you can cut the wait time down to 30 minutes.

Hal Weitzman: We don’t need to go to Delaware. We can do it all online. We don’t need to say that we are the owners of the company. We can make it an anonymous limited liability company. And we don’t need to show any kind of identification at all in order to set up this company. The Secretary of State’s office stays open until midnight so it can register companies. I mean, which other state agencies do you know that is that dedicated to making business easy? So the vast majority, about 70%, of the companies that are set up in Delaware every year are limited liability companies, LLCs. And so that’s where the don’t ask, don’t tell policy comes into effect because those LLCs are not required to report anything to anyone else.

Paul Rand: And that begs the obvious question. What kind of company needs to be created with complete anonymity, in under 30 minutes, at 11:00 at night? Well, possibly companies that are going to use this lack of transparency for maybe let’s say nefarious reasons.

Hal Weitzman: It’s definitely a legitimate concern. And there’s a slew of examples, Paul, many of which I discuss in the book, but maybe I’ll give you a few quick ones that flow through Delaware. So one is the 1MDB scandal where Malaysian officials used eight companies in Delaware to steal billions of dollars of public funds.

Tape: Well, the 1Malaysia Development Berhad Fund, or 1MDB, was set up in 2009 when the Najib Razak was Prime Minister. Malaysian and US authorities allege $4.5 billion were illegally transferred from it into offshore bank accounts and shell companies.

Hal Weitzman: Some of which ended up being used to make the movie The Wolf Of Wall Street, if you remember that one.

Paul Rand: Delaware businesses were used by international arms trafficker of Viktor Bout to disguise profits involving the trafficking of arms.

Tape: His crimes are the stuff of Hollywood. After agreeing to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to a rebel group on the US terrorist list, Viktor Bout was found guilty on four conspiracy charges by an American jury.

Hal Weitzman: Another example is LAN, the former Chilean airline. It’s now changed its name, but about 10 years ago, it paid bribes to Argentine labor union bosses using a Delaware LLC. So there we have kleptocracy, we have corruption.

Paul Rand: And there’s also plenty of domestic examples of people using Delaware LLCs for less than above board reasons.

Tape: Tonight, President Trump’s former campaign chairman Paul Manafort is a convicted felon who could spend the rest of his life behind bars. After four days of deliberations, the jury rendering its verdict, guilty on five counts of tax evasion, one count of failing to report a foreign bank account, and two counts of bank fraud.

Paul Rand: Paul Manafort conducted his tax evasion scheme using 16 companies, nine of which were in Delaware.

Tape: Porn star Stormy Daniels files a new lawsuit, this time claiming her former attorney, and President Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, colluded to manipulate her to benefit Cohen and President Trump.

Paul Rand: The money Trump’s lawyer Michael Cohen used to pay Stormy Daniels came through, well, you guessed it, a Delaware LLC.

Hal Weitzman: And then a really horrific case is Backpage.

Tape: Backpage.com is one of America’s largest classified websites, but it’s best known for selling sex. The majority of Backpage’s revenue is generated through prostitution related ads in its adult services section. Law enforcement officials have dubbed it the world’s top online brothel.

Hal Weitzman: In fact, at its height, Backpage was involved in three-quarters of the child trafficking reports received by the National Center For Missing And Exploited Children. This was a Delaware registered company, that even months after it was shut down by federal law enforcement in 2018, was still considered to be in good standing by the Delaware Secretary of State’s office, because they’d paid their annual fees. So there’s a case of human trafficking. There are cases of money laundering, of arms trafficking, of drugs trafficking, all not going through Delaware, but all using Delaware businesses. And as I say, with the protection of the United States law.

Hal Weitzman: It’s a way to dress up bad behavior. It puts a business suit and tie on activities like money laundering and drug trafficking by saying, “Well, we have a Delaware LLC. How more legitimate could you be?” Coca-Cola and Google have one as well. Now I should point out, there’s a huge difference between the kind of Apples and Googles, which are public companies and they are required to report a huge amount of information. But there’s a huge section of the US economy and the global economy that is made up of private companies, largely in Delaware, limited liability companies.

Paul Rand: Keep in mind, these examples are just the ones that got caught. It could be possible that even some terrorist organizations are using this system, meaning a US state could be undermining the national security of the federal government.

Hal Weitzman: Let me give you a much more recent example, which is when Russia invaded Ukraine, we said as a country that we want to strangle the Russian oligarch’s flow of money around the world. That was an effort that the UK and the European Union and the US kind of spearheaded.

Tape: The United States Department of Justice is assembling a dedicated task force to go after the crimes of the Russian oligarchs. We’re joining with European allies to find and seize their yachts, their luxury apartments, their private jets. We’re coming for you, ill begotten gains.

Hal Weitzman: The fact is in the US, one of the things that’s hampering that fight is we have no idea who is behind the companies that are formed in this country, because of this corporate anonymity. So it undermines our own foreign policy and national security because we don’t know where the oligarchs are operating. And it isn’t just idle speculation because there have been oligarchs who’ve been traced to Delaware LLCs, in one case somebody who was using a Delaware LLC to buy property in Washington. And the only way that came to light is not because federal officials charged anyone. It was because the Washington Post sent reporters around the neighborhood and the neighbors of this person identified that he was the owner of the house.

Hal Weitzman: So we have no idea, and in fact, when I was doing the research for this book, I just wanted to double check and I called the Secretary of State’s office in Delaware and said, “Just tell me a basic fact. How many of the companies registered in Delaware are US companies and how many are owned by people outside the US?” And they said, “We don’t know, and there is no way of knowing.” And that to me is a very scary situation, but also means that when we say we want to cut off funds to terrorist organizations or to Russian oligarchs, we are unable to do so because we just don’t have the information we would need.

Paul Rand: And finally, this anonymity structure even facilitates the influx of so-called dark money into politics.

Hal Weitzman: So we of course have Citizens United, which was a judgment that allows companies to give unlimited donations to political campaigns. And some people threw their hands up and said, “That’s the end of everything.” But there actually are some transparency rules in place. For example, a super PAC has to report its donors. One of the challenges, if you dig into that information, is often the donors are anonymous Delaware LLCs, which means that you and I don’t really know who’s funding the campaigns that we are being asked to cast our vote for. So this is another way, it’s not the only way, but this is another way that political campaigns can keep dark money dark.

Paul Rand: This idea about a lack of transparency seems to be a big crux of wanting to register in Delaware. We’re here in Illinois. Is there a different level of transparency necessary, for example, than there would be in Delaware?

Hal Weitzman: There are states that ask for ownership information, but one of the challenges is, imagine if you’re in a state that asks for ownership information, like Massachusetts being one, I could make the ownership of my Massachusetts LLC a Delaware LLC, which is anonymous. So in this way, it sets the standard, by allowing anonymous corporations, it sets the standard for pretty much anywhere.

Paul Rand: This is what Weitzman means when he says that Delaware is virtually escapable. Because of its corporate monopoly, the rules it sets become the competition for business every other state must meet. This even has had an effect on what interest rate credit card companies can charge you because, well, this shouldn’t be surprising, four out of the five largest credit card companies are registered in Delaware.

Hal Weitzman: Yes. And lots of other financial institutions as well. And that flows from a history that dates back to 1981, when there was a battle to attract the big New York banks and Delaware invited Chase Manhattan and J.P. Morgan, two of the biggest banks, to form a secret task force to write the laws that would govern Delaware and therefore the whole of the United States. Because if you think about it, if I’m allowed to charge unlimited interest, then that pertains everywhere. There’s nothing another state can do about that because once a credit card company registers in Delaware, the rules of Delaware apply, not the rules of the other states. So this neuters any attempt elsewhere to put interest rates caps in place. You may remember in the good old days before 1981, there were interest rate caps in many, many states, but Delaware effectively was able to help get rid of those. So the rules that they wrote in 1981 enabled lenders to charge unlimited interest rates, to raise interest rates retroactively, to levy unlimited fees, and to foreclose on homes belonging to people who defaulted on their credit card.

Paul Rand: And if this weren’t enough, Delaware also maintains this incorporation monopoly by helping businesses avoid paying taxes.

Hal Weitzman: I tell a story in the book about Ramon Fonseca, who was one half of Mossack Fonseca, the law firm, you might remember, that was based in Panama whose papers were leaked, and that was the Panama-

Paul Rand: Yes, the Panama Papers.

Hal Weitzman: Right.

Tape: The papers were a leak of over 11 million confidential documents, from the files of the Panamanian law firm. Mossack Fonseca. It’s one of the world’s biggest suppliers of secretive offshore companies. The papers revealed how the powerful and wealthy around the world hid money, dodged sanctions, and evaded tax.

Hal Weitzman: And so the story I tell is that an American investigative journalist went down there in the 1980s and interviewed Ramon Fonseca and he talked to him about all the different locales around the world. And at the end of the interview, he said, “So you help people hide money all around the world. Where do you keep your money?” And Ramon Fonseca said, quick as a flash, “In Delaware, they’ll never find it there.”

Paul Rand: Delaware has multiple ways it helps corporations avoid taxes. It even has its own loophole named after the state.

Hal Weitzman: Well, the Delaware loophole is an elegant tax dodge that makes Delaware a domestic tax haven for big companies.

Paul Rand: One of the best examples of a company using the Delaware loophole revolved around Home Depot.

Hal Weitzman: In the case of Home Depot, this is a company based in Atlanta, but registered in Delaware. In the 1990s Home Depot set up a company, they called Homer D Poe, a not very clever pun named after its lovable mascot. And this company, Homer, helped Home Depot dodge billions of dollars in taxes. So this is how it worked. They set up this Delaware subsidiary. They assigned to it all its trademarks. These are things like slogans, like “The Home Depot,” which is actually a trademarked slogan, or “where low prices are just the beginning.” And all the 1200 Home Depot stores around the US paid a proportion of their sales revenue to Homer to use those trademarks. So previously they had used those trademarks for free, but by creating this entity, they flowed billions of dollars through Homer. And here’s the kicker. Homer in Delaware didn’t have to pay any tax because Delaware doesn’t tax revenue from so-called intangible investments like patents and trademarks if the company isn’t physically located in Delaware. The rest of the company can write it off as a business expense.

Hal Weitzman: So in this case, this company Homer had four employees total. A lawyer, a paralegal, and two administrative assistants. But by 2000 it was earning revenues of $2 billion a year. So this is a well known tax dollars for Delaware loophole. In this case, the state of Arizona sued and won, but there are many other cases where that there’s not been legal action. It’s been used by companies like Toys “R” Us, Walmart, Gap, Ikea, Victoria’s Secret. Perhaps my favorite example, if I can just squeeze it in is WorldCom. You remember WorldCom, the old telecoms company, right?

Hal Weitzman: So WorldCom paid its Delaware holding company 20 billion over three years. And the intangible asset that it was paying for was so-called management foresight. So it was saying that the profits that the company made was supposedly made because of the superior skill of its top executives. So in this case, there is a very clear, it’s not really a loophole, I mean, it’s more like a deliberate policy to attract this kind of revenue. And of course the revenue doesn’t doesn’t flow to Delaware, they just get the fees. The revenue flows back to the companies. And so it helps the companies get richer and it helps the states that those companies are located in get poorer because they collect less tax.

Paul Rand: Well, when, when you think about a corporation, of course, not paying taxes and you have to just simply watch the news where you hear regular stories of the average wage earner paying more taxes than some major corporations, but there’s other things that’s causing problems. What else is being lost here in addition to not collecting taxes, when certainly you could argue that the country could really benefit and use them.

Hal Weitzman: Yeah. And I mean, so let me be clear. I don’t think anyone should pay more than they owe. I use TurboTax to make sure that I can take advantage of whatever tax breaks the federal government and Illinois state government gives me. But there are big costs to this kind of tax avoidance. One thing I think that’s being lost is obviously the revenues that would go to states and those could pay for support some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in our society. So the Delaware loophole, for example, allows companies to avoid corporate state income tax. And it’s contributed to a collapse in state corporate income tax revenues over the past five decades. And that has left states like Illinois with massive, crippling, debts. And it makes it more likely that ordinary taxpayers like you and me are going to have to pay more taxes eventually to make up for those losses.

Hal Weitzman: So that’s one big cost, is the cost to the other states. I think secondly what’s been lost is a sense of fairness in the tax system. And you talked about that. The biggest companies and the wealthiest individuals pay lower effective tax rates than small companies and middle class tax payers, which is anti-competitive really, if we’re charging smaller companies a higher effective rate of tax than bigger companies.

Hal Weitzman: And third, I think there’s a cost to our economic growth because companies spend a huge amount of resources on creative accounting to avoid taxes. That just shifts money around. They are not spending that money on creating new products and services and adding to the top line. It’s all about the bottom line and how we avoid taxes.

Paul Rand: And it’s not just wealthy companies that Delaware’s system helps avoid taxes. It’s wealthy individuals as well.

Hal Weitzman: Delaware is part of a system where the wealthiest people in the world in some years pay no federal income tax at all, not a penny. When you think about an LLC. An LLC can be a single individual. There’s also trusts, which are a well known way for people to defend their wealth, let’s put it that way. I’ll give you one example, which is the art market, and which is so fascinating, the largest unregulated market in the world.

Paul Rand: In fact, one third of the wealthiest people in the world participate in this market. Many speculate more for investment reasons than for a love of art.

Hal Weitzman: If you buy a painting at Christie’s in New York, you don’t have to identify who you are. You’re usually not in the actual auction room, it’s someone on the phone. And you don’t have to identify where the money comes from to buy the artwork either. So it’s a completely unregulated market and a huge market, of course. So if you buy a painting at Christie’s in New York, New York charges you 9% sales tax. So how do you avoid, let’s imagine on a $100 million dollar painting, it’s very significant sum, $9 million. You could use that to buy some more art. So if you want to save that money, you can take the art, put it in a truck, ship it directly to Delaware, where there is a so-called free port, which is a customs free zone. And it’s located in a former factory that used to make those foam packing peanuts, which have largely gone out of use.

Hal Weitzman: And so in that factory, they have created a high security, temperature controlled, art facility. You’ll never see the art, nor will the owners, because it has to be stored very carefully, but that’s where the art goes. Now it goes straight from New York there to Delaware where there’s zero sales tax and nobody pays any tax on that. So they’ve avoided paying tax in the city of New York. Then I can put that in a trust and I can hand that trust over to my heirs and my heirs can enjoy the art themselves and they don’t have to pay any tax when I hand the asset over. So we have a system that works for the very wealthiest. Let’s face it, most of us are not buying $100 million paintings. So it works for the very wealthiest to save them from paying taxes. And that’s kind of a microcosm of the entire tax system that the people who pursue and are most effective at getting tax breaks are not the middle class. It’s the uber wealthy.

Paul Rand: I’m not done, yet, to go into the solution because there’s another tentacle coming out of this beast that we’re painting a picture here. And that is this idea of bankruptcies. And so even if you’ve got this great advantage of all the tax savings that we’re talking about, if there is a bankruptcy, within something that happens in Delaware, how does that play itself out?

Hal Weitzman: Well, so Delaware is kind of for corporate life events. Companies go there to get born. If you continue the analogy, they go there to get married. M&A is all in Delaware, because that’s where they’re registered. And then they go there when they declare bankruptcy. So bankruptcy is a very nice business for Delaware. That’s a billion dollar business in itself. All of this is very beneficial to Delaware lawyers, who by the way, are the most expensive per hour lawyers in the world/ So you think Washington lawyers are expensive, you think New York, California, lawyers are expensive. Delaware lawyers charge more than any of them.

Paul Rand: Well, at this point, it’s pretty clear about what’s the matter with Delaware. But how do this system come about and what can we do to fix it? Well, that’s after the break.

Paul Rand: Not only is the lack of transparency a problem when it comes to the outcomes of Delaware’s system, the way that system itself operates suffers from opacity. One prime example is something called the Corporation Law Council.

Hal Weitzman: The Corporation law council is a group of 27 lawyers. They effectively write the code, and then they give the changes to the code to the legislature, which is full of part-time lawmakers. paid $40,000 a year, that has just four lawyers in it, and they do not have the capacity to scrutinize these proposed changes.

Paul Rand: And remember, because Delaware is everywhere, this one group of 27 lawyers effectively is writing the corporate code for the entire country.

Hal Weitzman: So what is the corporate code? It spells out the duties of executives to shareholders. And so 26 of them are working lawyers, Paul. So they go to court. They then argue under the rules that they themselves have set. So when we think about the way that decision making gets done in Delaware, it reminds me of the work of George Stigler, the famous University of Chicago economist who came up with the idea of regulatory capture. And for Stigler, regulatory capture meant that interest roots come to control law making and regulation of their own sectors, so that the regulators end up kind of being the lobbyists for the industries that they’re supposed to oversee.

Hal Weitzman: But in Delaware, they’ve kind of perfected and institutionalized that. So the lawyers don’t even need to lobby the legislature to change the corporate code. They just write it themselves. And we don’t even get the rationale for them. We just get the amendments to the corporate code themselves, and then the legislatures are called on to vote over something they really don’t understand. So I’ve repeatedly said to people from Delaware, “Doesn’t this feel a little bit like the fox guarding the henhouse?” And I’ve always been kind of shooed away.

Paul Rand: This question about being shooed away or other things that go into this. I imagine at this point, as people are listening, you ought to be pretty agitated. I’m getting agitated talking to you. And you start wondering, “Well, how in the world is this happening?” And we’re thinking about places, i.e., Illinois, where we are, where we’re dealing with all sorts of ways of making sure we’re covering shortfalls that come up in different areas that you’re making the case of is could be handled differently through taxation. How in the world is this not a problem? And based on everything that you’re saying, how is this not seen as a problem?

Hal Weitzman: Wow, you’re also asking me to get into the psychology of the entire legal and financial community. I think, because it’s been around for a long time, then it’s hard for people who are in that world to take a step back and think about the costs and the benefits of it. There are undoubtedly benefits. It’s an efficient system. The legal community, let me take that, legal scholarship has looked a lot at Delaware and they will say things like, “Well, this is very effective because we bypass any politicization.”

Hal Weitzman: And when I see that, I think that’s not a good thing. The politicization is that’s where society comes in. Companies tell us that they want to have a purpose. They want to be socially useful. Where does society appear? Well, normally it would appear in with the checks and balances with the politicians, but they’re not there. So that’s why one of the proposals I make is that we should add to that Corporation Council, lawyers who specifically represent workers, who represent the environment, and general social purpose, so that we get a better sense from them about are companies doing what they tell us they want to be doing.

Paul Rand: At some point, and probably intermittently throughout this, everybody’s probably sitting there saying, “Wait a minute? Isn’t our President from Delaware?” Isn’t our President from Delaware? He was a Senator there, for what, 36 years?

Hal Weitzman: Yes, he was. Yeah.

Paul Rand: And so clearly, If president Biden had thought that this was a problem when he was Senator or otherwise, he would’ve done something about it. But on the surface you look at this and say, “This is a problem.” And so what, if anything, has Biden said during his time in office about this is an issue?

Hal Weitzman: Well, I think it’s important to point out that he did not create the system, but he is very much a creature of the system. And I don’t just mean system of incorporation. I mean, the Delaware way, this behind closed doors type way of doing business. His style exemplifies the system. He’s been funded by the system and his voting record reflects the system. His whole pitch was, “I’ve got stuff done in the past in the Senate. I can do stuff in the future.” That’s very Delaware way, the whole sort of behind closed doors deal making type system.

Hal Weitzman: In terms of who funded his campaigns, so if you take out his Presidential campaign, but over those 36 years of his Senate campaigns, his biggest donors were the very law firms that write the rules and charge those highest hourly fees in the US. It’s the same law firms that you’ll see in the main square down in Wilmington that have their offices all around and are so influential in every aspect of Delaware life.

Hal Weitzman: And then in terms of his voting record, at times, he’s definitely acted to defend the interest of, for example, credit card companies. So Biden did not create the system, but he’s very much a creature of it.

Paul Rand: If we wanted to be fair to Delaware, it’s difficult to imagine them reforming this system without absolutely tanking the state in the process.

Hal Weitzman: That’s right. So the franchises, they call it, which is this incorporations business, this business formations industry, collectively amount to about 40% of Delaware’s state revenue. So there are huge benefits that flow into Delaware. They call Delaware a blue spending state with red taxes. So they have pretty low taxes relative to the rest of us. They pay about 50 cents for every dollar of services they receive. It does not encourage a lot of debate and scrutiny because it’s scared of losing this business. And when somebody puts the head above the parapet and has occasionally said, “Why are we doing this?” Or, “What are the implications of doing this?” They’re told, “Pipe down, unless you want your taxes to go up.”

Paul Rand: But Weitzman points out in his book that there are other opportunities to fix many of these problems.

Hal Weitzman: I didn’t want to write one of those books, Paul, where they say the solution is we need a global authority to do X, because I read those kind of books and I think, “Eh. That’s not going to happen. I enjoyed the book, but it’s very unrealistic.” So everything I argued, I tried to make very modest extensions to what’s already happening.

Paul Rand: One of those solutions that’s already underway is something called the Corporate Transparency Act.

Hal Weitzman: The Corporate Transparency Act was a bill that was passed in 2020 and was signed actually by President Trump in one of the last days of his administration. It was a bipartisan bill that essentially said this system of corporate anonymity has to end, so we are going to mandate that everybody who owns a company in the United States has to tell the federal government who they are, has to identify it’s so-called beneficial owners. And so we’re going to set up a registry. And I do have some issues with the registry because, for example, there’s a loophole there for trusts. The rules are still being written, but it appears there’s going to be a loophole for trusts. Well, that is going to be a challenge because of trusts are well known, for example, vehicle used by Russian oligarchs. So the first thing I would suggest is that we just close that loophole.

Hal Weitzman: The second challenge I have with the Corporate Transparency Act is we’re going to set up a registry of beneficial owners, of the true owners of companies, which by the way already exists in European Union and the UK. So we are catching up to that, to the global order, we’re not leading the pack at all. But the challenge is that that registry will only be visible to the Treasury and other federal government and law enforcement agencies. So that concerns me. First of all, there’s not a good history of inter agency cooperation between federal government, state agencies, and we’ve been down that road before and it’s not ended well. So I worry about that.

Hal Weitzman: And I also worry about the ability of the government to be able to verify and investigate the information that’s provided. Bear in mind that the agency that’s going to collect this information is a small unit in the Treasury called FinCEN, the financial crimes unit. It has about 300 employees. Currently, they are snowed under with red flag warnings from banks that have to trace, anyone who’s done a money transfer recently knows there’s much more stringent rules on anti-money laundering, so they have to trace where money comes from in and out of their institutions and they raise red flags if they’re concerned. Well, the Treasury is already overwhelmed. So 300 people are overwhelmed by red flags. Now we’re telling them we’re going to dump all the company ownership information on their heads. So that’s tens of millions of new documents that we expecting them somehow to go through, analyze, make sense of, and find their own red flags. And in order to do that, the Biden administration has said, “We want a bigger staff there.” So they’re expanding it to 400, which doesn’t fill me with a lot of confidence that they’ll have the capacity to do that.

Hal Weitzman: So my suggestion is that they make that registry public because we’ve seen that journalists, for example, through the Panama Papers and then more recently the Pandora Papers, which was another huge leak, even bigger, actually, the journalists are pretty good at following the money. And this could be a way to hold the uber wealthy and politicians to account. You may remember in the Panama Papers that that had a lot of political fallout because sitting politicians who were telling people, “You got to pay your taxes,” were themselves using offshore vehicles and not paying their fair share of taxes. So we have an obligation to the public to make this transparent.

Hal Weitzman: So that’s my second one. Then I just have two quick proposals about Delaware itself. This Corporation Council should, first of all, explain to the legislature what are the changes and why they necessary? The changes that it wants to make every year to the corporate code. And, second, because companies tell us they’re not just about making profits, but they have a social purpose, I do think it’s important that we bring in other lawyers who can offer the perspective of workers, of the environment, and of society in general, and to give us the best possible governance standards, who are independent of the lawyers who work for the companies themselves or for their shareholders. Now, these are all pretty modest goals, but they would be a good start on the road to a healthier balance between efficiency and transparency in our economic system.

Hal Weitzman: The thing that I’m trying to push for is just greater transparency. And I don’t think that transparency is a left wing, liberal, idea. I think it’s actually a very pro-business, pro-free market idea. Transparency improves capital formation, it improves price discovery, and it certainly improves regulation. I’ll just leave you with one thought, which is very recently there have been proposals put forward. We talked about some of the problems with the Corporate Transparency Act. Some of the states are acting on their own because they don’t think the Corporate Transparency Act goes far enough. And unfortunately, this has been prompted by Ukraine. So the impetus has not been a positive one, but the effect is very exciting. And that’s that in New York and in Alaska, which is a big home of trusts, there are proposals that will be voted on in New York, hopefully in the next couple of months, to force companies to identify their owners. All companies, I think, including trusts. So that’s a very exciting development. There is a push for greater transparency, and it’s not that I want Delaware to disappear off the map of the United States. I just want to open things up.

Hal Weitzman: In fact, I’ll tell you a funny thing that one of the working titles that we had for this book was Shut Down Delaware, like shut down the business. And then I said to my editor, “But it’s not about shutting down. It’s about opening up.” I just want, as they say, the sunlight to stream in so we have a better understanding of who owns the companies that benefit from the laws of the United States.

Episode List

From green burials to DIY funerals, how death in America is changing with Shannon Lee Dawdy (Ep. 92)

Anthropologist examines what our rituals reveal about society, especially after 9/11

Why we need to invest in parents during a child's earliest years, with Dana Suskind (Ep. 91)

Book examines how better policies can bolster families and boost early childhood development

The troubling rise of antibiotic-resistant superbugs, with Christopher Murray (Ep. 90)

Global health expert warns about a potential ‘pandemic in the shadows’

Is scientific progress slowing? with James Evans (Ep. 89)

Scholar examines how researchers could generate greater innovation and discovery

Could we vaccinate against opioid addiction? with Sandra Comer and Marco Pravetoni (Ep. 88)

Scientists discuss promising solution, now in clinical trials, to address drug overdose epidemic

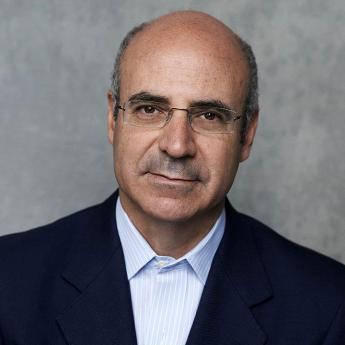

The man who fought to sanction Putin and Russian oligarchs, with Bill Browder

Businessman explains how his work on the Magnitsky Act made him country’s No. 1 enemy

Why big ideas fail to scale—and how to fix it, with John List (Ep. 87)

Economist discusses the secrets of using science to scale promising social programs

Could personalizing laws make society more just? with Omri Ben-Shahar (Ep. 86)

Exploring the benefits and pitfalls of using big data to tailor different rules to different people

How to stick to your resolutions, with Ayelet Fishbach (Ep. 85)

New book explores science of setting goals, achieving success and learning from failure

Engineering A Cure For Cancer, with Jeffrey Hubbell and Melody Swartz (Ep. 83)

How immunotherapy is changing everything