COVID-19 has had a disproportionate public health impact on Black and Brown communities across the United States, creating immediate and long-term challenges for the urban public schools who serve these communities, according to leading UChicago education experts.

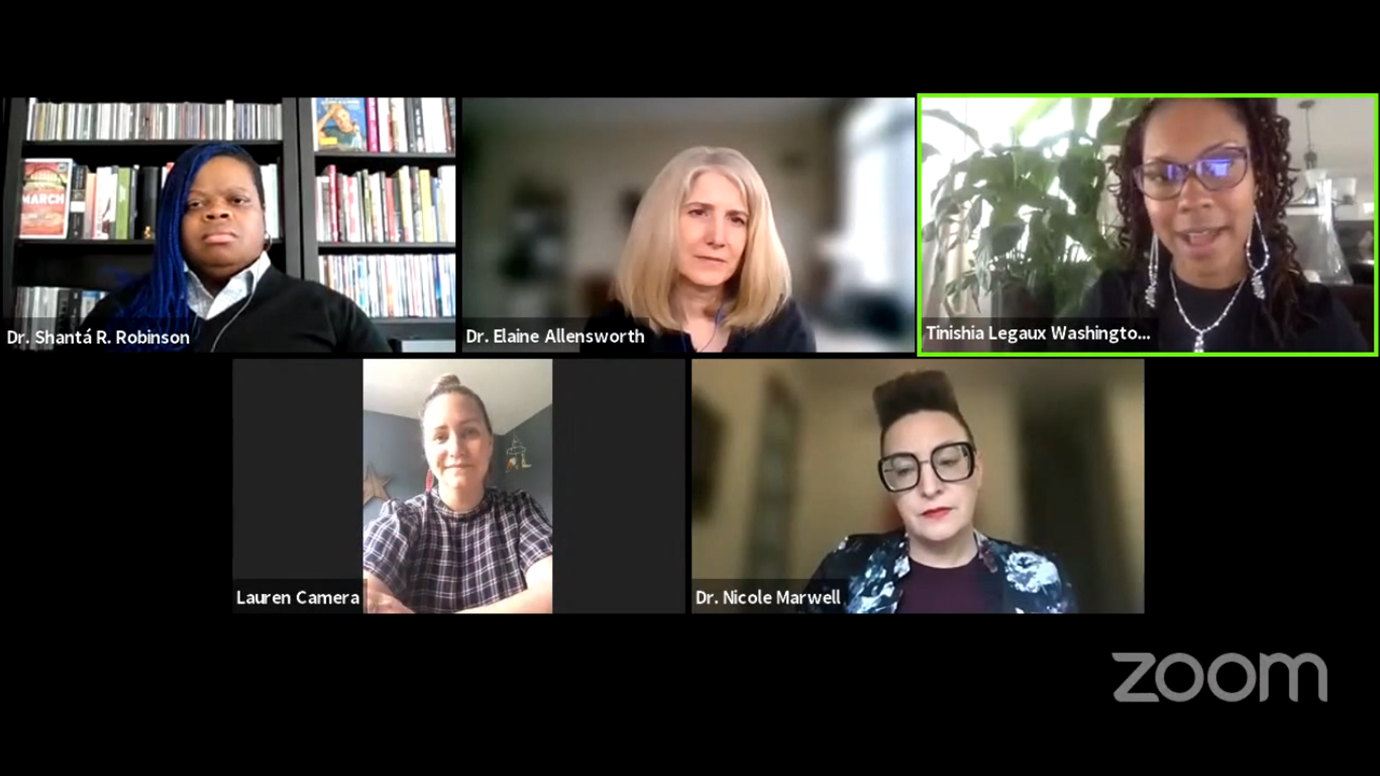

At a virtual event hosted by the UChicago Urban Network on April 29, education scholars and practitioners Elaine Allensworth, Nicole Marwell, Shantá Robinson and Tinishia Legaux Washington discussed the history of racism in public education and what schools need to consider as they move forward from a moment that has both exposed existing disparities and kept underserved students out of school for a year.

Among the issues they discussed were a lack of broadband internet access, food and housing insecurity, and physical health and safety. All of these are key factors for school districts and society to consider when evaluating the role that public schools will continue to play in supporting communities post COVID-19, according to the panel.

When it comes to restarting in-person learning in underserved communities, Robinson focused on the connection between mental health services for students—which have been traditionally under-resourced—and setting up students for academic success.

“Black and Brown communities were particularly hard-hit by COVID-19,” said Robinson, an assistant professor at the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy and Practice. “Schools have to understand that in order to connect to the academics, sometimes you have to also connect to the humanity in people.”

Robinson called for more mental health staff, like therapists and social workers, to help address the needs of students who have dealt with difficult social-emotional circumstances over the past year.

“I frame it as a reckoning: We have not reckoned with the more than half a million people who we lost to this disease; we haven’t reckoned with how the government failed us in those spaces; we haven’t reckoned with how it disproportionately impacted Black and Brown folks,” she said. Robinson is also concerned that without additional mental health resources now, urban schools could see a “discipline spike” in suspensions or expulsions of students who need support.

‘‘Schools have to understand that in order to connect to the academics, sometimes you have to also connect to the humanity in people.’’

The experts also highlighted the idea of reframing the “achievement gaps” and “teaching gaps” conversation into an idea of “education debt,” recognizing that students of color across the country are systemically set back by a series of policy decisions spanning decades.

One proposed remedy to begin addressing this “debt” and racism more broadly is to ensure that public schools recruit, support and retain more teachers of color.

Legaux Washington, who runs the UChicago Urban Teacher Education Program, talked about how her organization has prioritized supporting teachers of color and how important it is for students—not just for students who should see teachers who look more like them—but also so that white students are introduced to authority figures and leaders of color.

“The first step in retaining and recruiting teachers of color is for districts to really understand the value that teachers of color bring to the classroom,” Legaux Washington said. “There has been a lot of research around teachers of color who have been successful with students, particularly in urban settings, but also the understanding that a teacher of color who is successful is going to help all students and not just students of color.”

Robinson added: “When President Biden says we have a white supremacy problem in this country, we’re not going to solve it unless we first solve the problem of not wanting Black men and women in front of our children as people in power.”