An exhibit at the University of Chicago Library this winter contains a wooden baseball bat worn flat on one side, next to a bag of rocks collected from the slopes of a Japanese volcano. The bat belonged to UChicago geoscientist Prof. Alfred T. Anderson, Jr.

“Fred found that was the perfect tool for smashing rock samples,” said his colleague Prof. Andy Davis. “Just enough weight to crush the pumice without damaging the pieces of quartz inside.”

Anderson, a professor in the Department of Geophysical Sciences for nearly 40 years, also used the latest state-of-the-art scientific instruments for his work on understanding volcanic eruptions. But he also had a practical streak, Davis said. “Sometimes a baseball bat and a cardboard ice cream container are exactly what you need.”

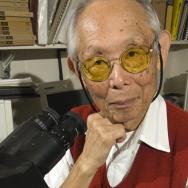

Anderson, who died Jan. 15, made pioneering contributions to the field of volcanology—particularly how to reconstruct long-ago volcanic explosions using clues in the rocks left behind. He was 82.

Born on Long Island, New York in 1937, Anderson spent his early years spending hours skipping stones at the beach. The fascination with rocks grew into a passion for geology, which he pursued at Northwestern and Princeton universities, and then with the U.S. Geological Survey. In 1968 he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago, where he would spend the next four decades.

Anderson’s work focused on a kind of glass that is often found embedded in volcanic stone from past eruptions. “His theory, and he was very alone in this at first, was that the dissolved gases in these inclusions were fundamental to understanding the conditions before and after the eruption,” said Davis, who worked alongside Anderson for many years and co-authored several papers with him.

There are many different ways for volcanoes to erupt, and scientists wanted to be able to tell what had happened in past eruptions: how the magma moved, how much gas was released, how far the lava traveled aboveground. Anderson’s argument was that each glass inclusion recorded a snapshot from the moment it was created over the course of the eruption.

Especially as the technology to extract and learn from such gases grew, Anderson’s studies “sparked a revolution in melt inclusion studies of volcanic rocks,” according to Charles Bacon with the U.S. Geological Survey, who presented Anderson with the Bowen Award in 2001, a prestigious honor in geology. “Nature has given us precious few tools with which to look backward in time in the reconstruction of geological processes. A special genius is often required to recognize one of those tools,” he said.

Anderson was known for the rigor and precision of his science. “He has led the field of melt inclusion research because he has noticed things, measured them and extracted information about processes others would have missed,” Bacon wrote.

His methods are now standard in the field.

He traveled widely to collect his samples, including volcanoes in Iceland, Hawaii, Japan, Alaska and particularly California, where he reconstructed the eruption that formed the Bishop Tuff, east of Yosemite National Park, 700,000 years ago. “It’s really important to be able to reconstruct these pieces of history, because this was unlike anything we’ve seen in recorded history,” Davis said. “Mount St. Helens was small compared to this volcano.”

Closer to home, Anderson was known for his willingness to take anyone who asked on a tour of the geology of the rock on the façades of buildings in downtown Chicago. For years, he and his wife also served as the resident masters for the Snell-Hitchcock residence hall.

He was also an enthusiastic athlete, playing baseball with his two sons and taking them hiking and camping; for many years, the family traveled with UChicago students on summer field trips to collect rocks on the slopes of Mount Shasta.

Anderson is survived by his sister Almeda, wife Caroline, sons Eric (Sinane) and Doug (Colette), as well as grandchildren Payton, Quincy, Gisele and Sonia.