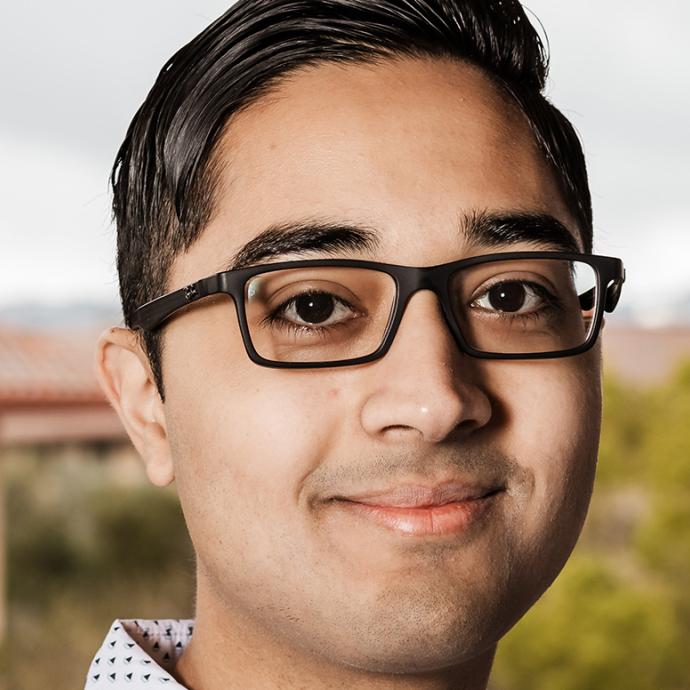

Prof. Eugene Parker had never seen a NASA launch in person until Aug. 12, 2018—when a spacecraft honoring the pioneering University of Chicago astrophysicist blazed through the predawn skies, beginning its ambitious mission to the sun.

Six decades after Parker wrote a groundbreaking paper that shaped how we view the solar system, the launch of Parker Solar Probe was not only historic but also emotional for the 92-year-old scientist.

“So much has gone into this launch, and then to see it all disappear slowly—fading away into the night sky, knowing it will never come back—it was a moving experience,” Parker said.

In the year since, Parker has been receiving updates on the NASA mission, which has already come closer to the sun than any spacecraft. Parker recently visited with Nicky Fox, director of NASA’s Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, at his Hyde Park apartment and learned that the spacecraft is running perfectly—and has gathered twice as much data as originally predicted.

“Parker Solar Probe is blazing a trail as she orbits through the corona; she’s behaving beautifully,” said Fox. “We’re actually very excited because we have more than twice as much data as we had expected.”

Parker Solar Probe has circled the sun twice thus far, and on Sept. 1 will reach its closest point to the star yet.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He