Show Notes

If there is something both sides of the political aisle can agree on, it’s that there is something deeply wrong with health insurance in the United States. What they can’t agree on is how to fix it. The right blames everything on the Affordable Care Act, while those on the left say we need Healthcare For All. But what if there was another option?

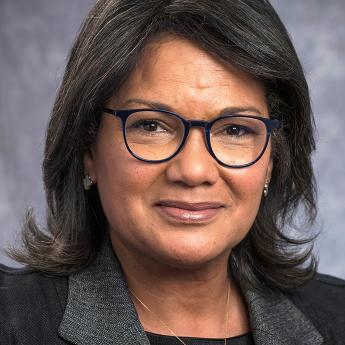

In a recent paper published in JAMA, leading health economist and University of Chicago Provost Katherine Baicker lays out an innovative blueprint for health care—not to tinker with our system on the margins, but to redesign the entire thing. It’s a fascinating idea that takes us through the complex history of health insurance, how that web got so tangled up and how we can straighten it out.

Baicker is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, the National Academy of Social Insurance, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She serves as a Director of Eli Lilly, where she chairs the Ethics and Compliance Committee; and as a Trustee of the Mayo Clinic. She is on the Congressional Budget Office’s Panel of Health Advisers and is a member of the Advisory Board for the National Institute for Health Care Management. Through her role as Provost, she is a Trustee of Argonne National Laboratory, the Marine Biological Laboratory, NORC, and the University of Chicago Medical Center.

Subscribe to Big Brains on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher and Spotify.

(Episode published June 1, 2023)

Subscribe to the Big Brains newsletter.

Please rate and review the Big Brains podcast.

Related:

Transcript:

Ad: Will everyday investors and shareholders shake the foundations of capitalism by seeking a greater voice in corporate boardrooms? Join Chicago Booth’s Rustandy Center and Stigler Center, in partnership with the Financial Times, for a virtual event on June 14 – Shareholder Democracy: Is a Revolution on the Horizon? – the second in the Unpacking ESG series. Featuring UChicago’s Luigi Zingales and University of Pennsylvania’s Lisa Fairfax, the panel will be moderated by the FT’s Simon Mundy, register here.

Ad: How can we improve communication at work? Are stock markets really efficient? Should we let algorithms make moral choices? How will climate migration affect our societies? The Chicago Booth Review podcast addresses the big questions in business policy and markets with insight from the world's leading academic researchers. We bring you groundbreaking research in a clear and straightforward way. It could help you make better decisions, work smarter, and maybe even become happier. Find us wherever you get your podcasts.

Paul Rand: If there is something that both sides of the political aisle can agree on, it’s that there is something deeply wrong with health care in the United States.

Tape: One thing that experts across the political spectrum agree on is that health care in America often cost too much.

Tape: Why does American medicine cost so much? And if we’re going to pay so much for it, why don’t we get better results?

Paul Rand: And while everyone may agree we have a huge problem, what they can’t agree on is how to fix it.

Tape: President Trump knows that every day Obamacare survives is another day that American families and American businesses struggle.

Tape: The United States of America, our very great country, is the only nation in the entire industrialized world that does not guarantee health care to all people as a right.

Paul Rand: It feels as if we’ve been on a never ending merry-go-round since 2010. The right blames everything on the Affordable Care Act, even though they can’t muster the votes to change it. While those on the left say we need health care for all, even though it’s politically outside the realm of possibility.

Tape: Democrats impose Obamacare on our country. They said costs would go down, costs skyrocketed. They said choice would go up. Choice plummeted. Now Obamacare’s years long lurch toward total collapse is nearing a seemingly inevitable conclusion.

Tape: Look at the business model of an insurance company. It’s to bring in as many dollars as they can in premiums and to pay out as few dollars as possible for your health care. That leaves families with rising premiums, rising copays, and fighting with insurance companies to try to get the health care that their doctors say that they and their children need. Medicare for all solves that problem.

Paul Rand: Meanwhile, Americans are stuck in the middle.

Katherine Baicker: I think anyone designing a health care systems from scratch would not design the system that we have.

Paul Rand: That’s Katherine Baicker, one of the leading health economists in the world. She serves as provost of the University of Chicago, and previously was Dean of the Harris School of Public Policy.

Katherine Baicker: The share of people who would say that they like our health care system is going down and down and down for good reasons, and maybe it’s a moment where we can actually think about transformation to a different system.

Paul Rand: And that’s exactly what has done. In a recent paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association or JAMA, she has laid out an innovative blueprint for health care in the US. Not to tinker with our system on the margins, but to redesign the entire thing.

Katherine Baicker: What I worry about with incremental changes is that they continue to build on this increasingly dysfunctional system in a way that bakes in some of the problems that we have. So if we approached health reform from a different vantage point, rather than trying to patch tiny holes in a very, very leaky health care system one by one by one, I think that we could not only achieve a more efficient system, but we could also have more rational decision making about what our public policy priorities are.

Paul Rand: It’s a fascinating idea that takes us through the complex history of health insurance, how that web got so tangled up today and how we can straighten that out.

Katherine Baicker: And I think implementing a transition plan that is thoughtful about continuity of coverage, continuity of care, smooth transitions over years, I think would be crucial for the success of introducing these elements that we’re talking about.

Paul Rand: And with tens of millions of Americans uninsured in an era of ever declining health, the stakes have never been higher.

Katherine Baicker: We have much higher rates of obesity and heart disease. We come into the health care system a lot sicker in many cases than people in the European countries that we’re being compared to. So it costs more to take care of us.

Paul Rand: Welcome to Big Brains where we translate the biggest ideas and complex discoveries into digestible brain food. Big brains, little bites from the University of Chicago Podcast Network. I’m your host, Paul Rand. On today’s episode, a new way to design health insurance in the United States. Well, before we get into your latest JAMA piece, why don’t we just go back a little bit, Kate, and tell me what initially caught your fancy on health care policy and economics?

Katherine Baicker: So I’ve always been interested in how we can structure public programs to make the safety net as robust as possible, and to be able to afford all the programs we want for housing, for health care, for schools, for food, and the way we structure those public programs makes such a huge difference in people’s lives. I started out as a public finance economist, really caring about how we make sure we have the resources for public programs. But once I started studying the U.S. health care system, it’s so complicated and it’s so vitally important, but has so many areas where it’s not living up to its promise. I decided that’s where I wanted to devote my efforts.

Paul Rand: Well, and in your JAMA paper, you take a bit of a historical perspective here. So why don’t we start there and talk to me about health insurance in the United States and how we kind of got from where we were to where we are. There’s what 10% of the population is uninsured right now, is that right?

Katherine Baicker: So almost 10% of the population in the U.S. is uninsured.

Paul Rand: And if you think about that in coverage in relation to other developed nations, how does that 10% figure, in our case, it’s about 33 million people. How does that 10% add up in relation to others?

Katherine Baicker: We are way above other developed countries. Our OECD trading partners in the share of our population that’s uninsured, most developed countries have driven that number down to near zero. A natural question is, why are these people uninsured? Why are they falling through the cracks of our system? Well, there are a lot of different reasons. A lot of it comes down to this wacky patchwork that we have of private insurance and public insurance. And why is the system set up the way it is? Well, it goes back to some decisions that were made around World War II and even before. Back around World War II, there wasn’t a lot of private insurance in the US or anywhere else.

Tape: We are rightly proud of the high standards of medical care we know how to provide in the United States. The fact is, however, that most of our people cannot afford to pay for the care they need.

Katherine Baicker: Because of some price and wage controls that were in place around World War II in the US.

Tape: We should be compelled to stop workers from moving from one war job to another as a matter of personal preference to stop employers from stealing labor from each other.

Katherine Baicker: It became attractive for employers to offer health insurance as one of the benefits of working in addition to wages and anything else. And there was a decision that those benefits weren’t taxable, unlike your wages and that baked in a system in the US where a lot of our health insurance comes through our jobs. Most people who have private insurance in the US get it through their employer or their spouse’s employer or their parents’ employer. And that really accelerated during that 1940s, 1950s period. Well, one of the problems is that when you retired from your job, you lost your health insurance.

Tape: The Harry S Truman Library at Independence, Missouri is a scene of an historic event. President and Mrs. Johnson and Vice President Humphrey arrive for ceremonies that will make the Medicare bill a part of social security coverage.

Katherine Baicker: So Medicare came in 1965 to cover people who were otherwise going without vital care and losing their homes and their family’s wellbeing when they got sick. So before the advent of Medicare, which covers people over age 65 in the US along with some others, older people who had retired who were at the period of their lives where they needed health care the most usually didn’t have insurance. And so an expensive illness would not only mean they didn’t get the care that they needed but would bankrupt them and their families.

Tape: The new bill expands the 30-year-old social security program to provide hospital care, nursing home care, home nursing service, and outpatient treatment for those over 65.

Paul Rand: Then everything changed in 2010.

Obama: Today after almost a century of trial, today after over a year of debate, today after all the votes have been tallied, health insurance reform becomes law in the United States of America.

Katherine Baicker: With the advent of the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare, millions of people who had been uninsured got insurance either through Medicaid or through subsidized health insurance exchanges or through their parents’ plans.

Obama: And today the ACA hasn’t just survived. It’s pretty darn popular. And the reason is because it’s done what it was supposed to do, it’s made a difference. First 20 million and now 30 million people have gotten covered thanks to the ACA.

Katherine Baicker: And that really cut the rate of uninsurance, but it didn’t cut to zero. There are still millions of uninsured people in the US. So now we have the system where privately insured people are getting their insurance because of their jobs and older people are getting their insurance through Medicare and low income people who don’t have insurance through their jobs may or may not be getting it through Medicaid, which varies a lot state to state. So we have an incredibly patchwork system and there are plethora of other programs including the Children’s Health Insurance Program or CHIP, there’s in care for veterans through veterans benefits and active military through TRICARE.

So they’re all of these different programs and the rules for Medicaid vary state to state. So what insurance you have depends a lot on where you live and what your income is and what your family structure is like, and that is not good for continuity of care. So almost 10% of the population in the US is uninsured. There’s some groups that are excluded from many avenues of coverage like undocumented residents, like low income people in states that have not chosen to expand Medicaid. So there’s some groups that are not eligible for some of these programs, but a huge share of the people who are uninsured actually are eligible for free or very low cost insurance and they’re not enrolled. So it’s not just about affordability, it’s about other things too.

Paul Rand: Do we know from your research if there’s an overwhelming set of reasons why they’ve chosen not to be insured?

Katherine Baicker: People have been studying this question from lots of different perspectives. So there’s a body of research that suggests that some of it is about lack of information. People don’t know what plans are available to them and how much they really cost. Some of it is about non-financial barriers to enrollment. The required documentation to show that you are income eligible and citizenship eligible in all of other those categories or the paperwork that’s necessary to take advantage of those benefits. Some of it may be about misperceptions about the value of health insurance itself because on any year when you’re not using health insurance, anything you pay for premium seems like it’s wasted because it’s providing financial protection against something that didn’t happen.

Paul Rand: All right, so then there are political and financial pressures that step in to make this more complicated. Talk to me about what, if any, are the political pressures that make this situation challenging?

Katherine Baicker: Well, I am a simple economist, and so the realm of politics is often baffling to me, and there are lots of examples of where the political system or forces outside of economics seem to be keeping us where we are. For example, the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare let states expand Medicaid eligibility to all of their population that was under 133% of the poverty level, which many states had not done in advance of that law, and the federal government picked up the vast majority of those costs. So if you are a state governor or legislator, your choice is, would you like to give low income people in your state insurance that they don’t currently have paid for by the taxpayers in other states? The economist would say, “Yes please.” Yet many states chose not to expand Medicaid, and that shows that it’s not just about the economics, it has to be about ideological concerns, the politics, other things that are at play.

It’s also become increasingly difficult to get through modest health reforms that almost everyone would describe as common sense. There are some glitches in the ACA or Obamacare as originally constructed. Incompatible definitions of income based on individual income or family income, notches in eligibility that were never intended by the legislation. In times where there was reasonable cooperation across the aisle, I think that these would be seen as common sense technical fixes. Yet it is almost impossible to get anything like that done right now. And if you look at the history of Medicare, where we started, this is a more than 50 year old program has been amended countless times because it is incredibly complicated and there’s always something that needs addressing. If you live in a world where you can’t do technical fixes in a sector that accounts for almost a fifth of the economy, that is a problem.

Paul Rand: And so there is a cost of course when we have so many uninsured people. What is that cost?

Katherine Baicker: First and foremost, the cost is to be uninsured. When you have health insurance, you have access to more health care, to higher quality health care. You get health care earlier, you have better health outcomes, you have greater financial security. It is much, much better to be insured than to be uninsured. To me, that’s the main cost of uninsurance.

Paul Rand: But there are also costs imposed on our system by having such a high number of uninsured people. Uncompensated care or the care received by uninsured people that is never reimbursed is roughly $40 billion annually.

Katherine Baicker: There are many people who fall through the cracks. It poses an incredible administrative burden on health care providers to have to deal with so many different insurers. It is wildly inefficient in many ways.

Paul Rand: You also talked at your paper about this idea of it being a problem with something called job lock, and I wonder if you can explain that for us.

Katherine Baicker: The real problem that became incredibly salient during the pandemic is that if you move jobs, if you lose your job, if you retire, you risk losing your health insurance and that makes it very costly to leave your job. So some people who are in jobs that are not the ones they want, that are not a good fit, that are not working out well stay just because of the health insurance, because if they went to get a new job, they might not have any insurance at all or they might face much higher premiums. That stickiness in your job because of your health insurance is called job lock. And it means that not only are health insurance markets not operating efficiently, our labor markets aren’t operating efficiently.

Paul Rand: And we all pay a price for that lack of efficiency in lost wage gains, decreased economic output, and new businesses that may never be started. But that’s not all. Our current system also warps the incentives of insurance markets, which could be affecting the health of even those with insurance.

Katherine Baicker: Yet so much of our long-term health outcomes are based on things we do over many years and health care that we get over many years. In our current system, you’re not insured by the same insurer for all that long, and when you turn age 65, usually you switch over to Medicare. So if you are an insurer of a population that is say 45 to 65, there are really limited incentives to invest in that population’s health in a way that will forestall the heart attack that would occur when people turn 70. So no insurer has a long-term relationship with you to invest in your health for the long term. If we instead had a system where insurers were paid based on how well they managed a population’s health, if they lowered your risk of a future heart attack, that’s good health care, whether you have the heart attack, whether you would’ve had the heart attack at age 70 or 75, it’s good health care for lowering your future risk and it would be great to have a health care system that incentivize that kind of investment.

Paul Rand: Obviously, this system is broken in so many ways, but solutions are few and far between. The most prominent is the idea of moving to a Medicare for all system.

Katherine Baicker: There’s a lot of conversation about Medicare for all and having that as a mechanism for universal health insurance. What we propose instead is the idea of a basic insurance plan for all.

Paul Rand: That plan after the break.

Ad: Are companies that support ESG principles driving their own political agendas or are they looking out for the long term interests of shareholders? Join Chicago Booth’s Rustandy Center and Stigler Center, in partnership with the Financial Times, for a virtual event on June 21 – Is Corporate ESG Woke Capitalism? – part of the Unpacking ESG series. Panelists include Chicago Booth’s Marianne Bertrand; Former SEC Chairman Jay Clayton, Lafayette Square Founder and CEO, Damien Dwin. Moderated by Financial Times’Patrick Temple-West. Register at: chicagobooth dot e-d-u slash unpackingESG.

Katherine Baicker: As a society, we decide on an amount of health insurance that we think everyone should have access to, a floor for access to health care. Now we can decide how high that floor should be. When I describe it as a floor, it sounds minimal. It can be at any level of access to health care, but we decide collectively, we want to make sure everybody has at least this much health care. Above that, people could then buy additional health care out of pocket or through wraparound insurance plans and have access to more services, but people would be guaranteed universal access to that basic policy, and importantly, enrollment would be automated such that there wouldn’t be those non-financial barriers to care in addition to there being no financial barriers to care.

Paul Rand: This sounds like how I always understood the concept of universal healthcare. Is it the same thing?

Katherine Baicker: There are a lot of problems in my view and my co-author’s view with Medicare for all policies, including the risk of shortages of care or limited access to care, skyrocketing expenses, really tough decisions for a monolithic insurance policy that might not meet the needs of a very diverse heterogeneous population. The difference is I think a lot of people mean all available health care for everyone when they say universal health care. And people often come to that by asking the very important question, is healthcare, right? I think that that question is ill posed. You didn’t say it, I said it, but I think it’s an ill posed question because health care’s not one thing. Health care is a continuum of things from the very high value to the very low value, sometimes even harmful things that happen to patients. If you said, “I want public insurance to cover all possible care for all possible people,” that is more than 100% of GDP. That leaves you no money for food or education or housing or anything else.

Paul Rand: Okay. Wow.

Katherine Baicker: So you have to make some decisions about what is covered in your universal insurance product and even countries that have universal public insurance as a lot of the other developed countries do, actually have something that sounds a little bit more like what we’re describing than you might think. There is a lot of supplemental insurance purchased in many countries that have universal care or there is a lot of working outside the system to get care for systems that don’t allow you to purchase that wraparound coverage. So one way or another, either explicitly or implicitly, there have to be limits to what’s covered by a public insurance plan if you want to have money left over for other public policy priorities. And that’s the tough conversation that we need to have. Not whether health care is a right, but how much health care is a right.

Paul Rand: That’s a big shift of a question, isn’t it? A very sticky one.

Katherine Baicker: It sure is. It makes people really uncomfortable to postulate that not everybody is going to have the same health care, that high income people are going to get more health care than low income people and have better health outcomes. The reality is that happens now and there are lots of low income people or people living in underserved areas who get much too little health care. So having a real conversation about where we want to guarantee access would let us make sure that nobody has care below a threshold. Now, the trick there is defining what we mean by a minimum bundle of health care. I don’t mean only cheap care, I mean only high value care.

Paul Rand: Sorry. What does high value care mean?

Katherine Baicker: High value care is care that produces a lot of health for every dollar spent. There’s some very expensive kinds of care that produce transformative health benefits. That’s high value.

Paul Rand: Give me an example of that.

Katherine Baicker: For example, there are drugs that cure hepatitis C. People with long-term hep C often need liver transplants, have much shorter, much less healthy lives. If you can cure that, that is an enormous health benefit. That’s worth spending money on. And those drugs are expensive, but they’re still high value in my book because they’re producing such enormous health benefit. Now, on the other hand, there’s some cheap care that produces no health benefit, that’s low value. Think about antibiotics for viral infections where they’re ineffective, MRIs for low back pain where it’s contraindicated. There is a lot of health care that people get that is of very questionable health benefit. That’s low value. And I don’t think that we can afford for public insurance programs to cover that kind of care if we want to make sure there are resources to cover high value care for everyone.

Paul Rand: There is a question that everybody is listening right now is wondering, it’s like who’s paying for this?

Katherine Baicker: So that is the key question, and economists are notorious for being willing to put a price tag on anything. And people say, “Oh, you can’t put a price on your health,” but of course you have to put a price on these things or you can’t allocate resources effectively. And we care very much about health and housing, end food and education. So I keep coming back to saying we need to think rationally about where we want to devote our resources. What’s the best use of these scarce resources? Fundamentally, if more people are going to have access to publicly funded insurance, taxes have to go up. And that is one of the challenges is that the people who benefit from expanded public programs are often different from the people whose taxes are going up. And that creates a real question from policymakers is how they value those two things.

But we would also be shifting some spending away from private insurance spending. So you, taxpayer might be spending more in taxes less, but not zero in private insurance. But if you are not one of the people who was getting too little insurance before, your total cost may go up. We cannot pretend that this is free. And I think there’s a fiction people like to tell themselves that somehow if you cover the uninsured, it’s going to make health care so much more efficient and people are going to go back to work and they’re going to pay more in taxes and they’re going to use less health care down the road because they’re getting so much more effective care now that somehow we’ll all save money.

My reading of the evidence is that covering more people costs money. They use more health care, someone has to pay for it, and therefore it has to be a public policy priority to say we care about the wellbeing of the people who have inadequate access to health care and are willing to pay more spread across a lot of other people to make sure that that access is improved. We ought not to dilute ourselves that that is free.

Paul Rand: You do a lot of survey work even with NORC here at the University of Chicago. What’s the American public’s appetite for tackling this type of a challenge and being open to a change?

Katherine Baicker: Well, my colleague, [inaudible 00:27:41] Chandra and I did a survey with the AP NORC here at U Chicago asking preferences about your own health insurance and the health insurance coverage of other people in your community. And we looked at that based on all sorts of characteristics of individuals, including which political party you were affiliated with. And people on both sides of the aisle care about other people’s insurance coverage as well as their own for altruistic reasons not just because I’m worried about getting diseases from my neighbors, but because I’m actually worried about my neighbor’s wellbeing.

Paul Rand: Okay. Given that potential appetite for change as our last question, what do you look out and see on the health care policy landscape happening over the next five to 10 years?

Katherine Baicker: I have to say that I’m not optimistic about wonderful changes coming out of Washington anytime soon. That said, there’s a lot of policy activity at the state level and how you feel about that probably depends on which state you live in and what your preferences are, but I suspect there will be a lot more experimentation with alternative payment systems, with different insurance products at the state level than we’re going to see at the national level for the foreseeable future.

Matt Hodapp: Big Brains is a production of the University of Chicago Podcast Network. If you like what you heard, please leave us a rating and review. The show is hosted by Paul M. Rand and produced by me, Matt Hodapp and Leah Ceasrine. Thanks for listening.

Episode List

What Remains Unanswered After The 2020 Election, with William Howell and Luigi Zingales (Ep. 58)

UChicago economist and political scientist discuss the polls, what lies ahead for Biden and the country post-Trump

When Governments Share Their Secrets—And When They Don't, with Austin Carson (Ep. 57)

Scholar discusses the political theater of foreign policy—and the case for declassifying intelligence

How We Can Fix a Fractured Supreme Court, with Geoffrey Stone (Ep. 56)

Legal scholar examines how nomination of Amy Coney Barrett could tip an increasingly politicized bench

Correcting History: Native Americans Tell Their Own Stories (Ep. 55)

How scholars helped a Chicago museum rethink its representation of Indigenous peoples

The Future of Voting And The 2020 Election, with Assoc. Prof. Anthony Fowler (Ep. 54)

A leading political scholar discusses voting by mail, mobile voting and why he thinks it should be illegal not to vote.

Why The Quantum Internet Could Change Everything, with David Awschalom (Ep. 53)

A world-renowned scientist explores quantum technology and why the future of quantum may be in Chicago

The Way You Talk—And What It Says About You, with Prof. Katherine Kinzler (Ep. 52)

A leading psychologist explains how speech creates and deepens social biases

From LSD to Ecstasy, How Psychedelics Are Altering Therapy, with Prof. Harriet de Wit (Ep. 51)

A leading scientist explains the medical impacts of psychoactive drugs and the popularity of microdosing

How Can We Achieve Real Police Reform? with Sharon Fairley (Ep. 50)

Legal scholar examines whether civilian oversight, policy changes could increase accountability

Black Lives Matter Protests: Hope for the Future? (Ep. 49)

University of Chicago scholars examine the changing conversation around racial injustice and police reform