Show Notes

It feels like our world has never faced so many crisis all at the same time, and trying to solve them at once seems impossible. But, in 2015, the United Nations came together to develop a list of 17 Sustainable Development Goals, a blueprint for addressing all of humanity’s problems—from poverty to climate change to peace and justice. And, amazingly, every UN nation signed it. So, how is it going?

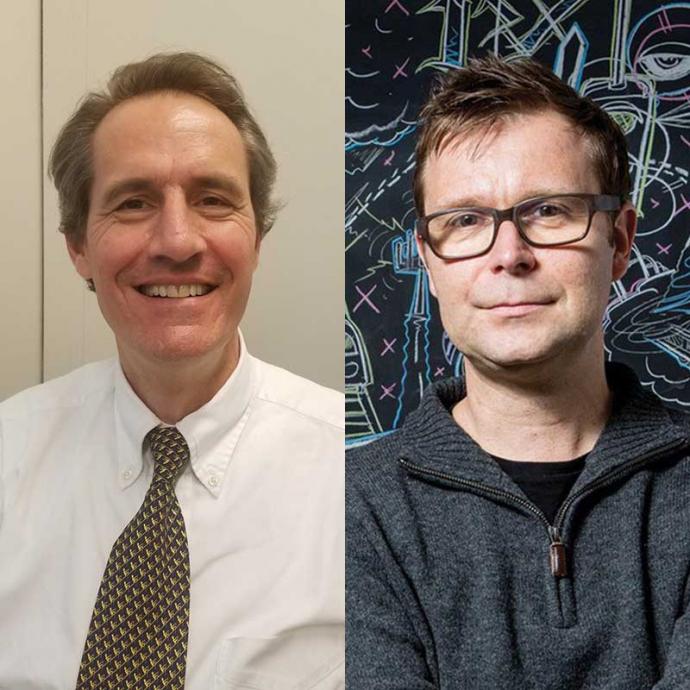

On this episode, we talk with Chris Williams, the director of UN Habitat; and Prof. Luis Bettencourt, director of the Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation at the University of Chicago, to get some insight on how they've been studying and working on these goals, as well as their perspective on the current state of our global crisis moving forward.

Subscribe to Big Brains on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher and Spotify.

(Episode published October 21, 2021)

Read more about Luis Bettencourt:

- UChicago Focuses on the Future of Cities in a Post-COVID-19 World—WTTW

- The Future of Cities after the Pandemic—UrbanLand

- Study Finds Large Cities Promote Lower Rates of Depression—WTTW

- How do cities impact mental health? A new study finds lower rates of depression—UChicago News

- COVID 2025: How COVID-19 will challenge and change cities, with Luis Bettencourt—UChicago News

- Big Brains podcast: Saving Our Cities By Studying A Million Neighborhoods With Luis Bettencourt (Ep. 34)—UChicago News

Read more about Chris Williams:

- New England Forests Can Help Slow Climate Change. A New Report Shows Exactly How Much—WBUR News

- Is deep-sea mining a cure for the climate crisis or a curse?—The Guardian

- The Pandemic Changed The World Of 'Voluntourism.' Some Folks Like The New Way Better—NPR

Transcript:

Paul Rand: Goal number one, in poverty in all of its forms.

Luis Bettencourt: I feel, but I think a lot of people, I feel, certainly my students feel, they’re in this pivotal moment in history, right?

Paul Rand: Goal six, ensure availability and sustainability of clean water for all.

Chris Williams: The international community came together in 2015 to say, not just how should we work together, but what are the things that are really important.

Paul Rand: Goal 10, reduce inequality within and among countries.

Luis Bettencourt: It feels like. We’d never had so many crisis, the crisis of climate, the crisis of biodiversity, the crisis of just, the crisis of prosperity for the future, the crisis of politics. What is the plan? And the sustainable development goals are the plan.

Paul Rand: In 2015, the United Nations came together to develop the sustainable development goals or SDGs. They’re a blueprint for tackling 17 interconnected global goals in order to create a better future for humanity.

Chris Williams: And a lot went into developing indicators that could actually be measured, rather than things that would be impossible to measure, and you would just hope and aspire to them achieving.

Paul Rand: This is Chris Williams.

Chris Williams: I’m the director of the New York office of UN Habitat. UN Habitat is the part of the UN system responsible for housing and urban development.

Paul Rand: That other voice that you’re hearing is Professor Luis Bettencourt, the Director of the Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation at the University of Chicago.

Luis Bettencourt: And it’s dedicated to understanding cities and urbanization scientifically and through bringing together people from multiple disciplines. It’s also dedicated to training people. We call it training the next generation in the methods, the perspectives and the knowledge that is required to understand cities and urbanization to the 21st century as a mixture of local and international studies, as well as technology and data and scientific tools.

Paul Rand: Both of these people and organizations are dedicated to working on the 17 SDGs set by the UN, specifically as they relate to urban development. So in honor of it being Urban October at the university, we’re going to explore where the world is with these goals and where we’re going.

Luis Bettencourt: So the sustainable development goals achieve something amazing, which is that every government on earth, that’s part of the UN, sign them, they’re committed to them.

Paul Rand: From the University of Chicago Podcast Network, this is Big Brains, a podcast about the pioneering research and pivotal breakthroughs that are reshaping our world. On this episode, a global project for sustainable development. I’m your host, Paul Rand. 17 worldwide goals are a bit too much for a 30 minute podcast to cover. But if there’s an overarching focus, both Chris and Luis have that interconnects most of them, it’s the power of urbanization.

Luis Bettencourt: The world’s been urbanizing very quickly. This means both central cities and suburbs together. So it’s not just the central part of cities, but the big, most spectacular change has really been happening in Asia, and now in Africa, where populations are really coming to live in cities to have similar experiences to what we’ve had in the United States and in Europe and other parts of the world. And as those populations account for a large part of humankind, we see rates of urbanization rise in almost every country, most notably in China over the last couple of decades, but increasingly now looking ahead at India and Africa.

Luis Bettencourt: And so this means essentially that a lot of what is happening today, when you talk about many of the crisis, and many of the challenges ahead, is really something that’s happening through the experience of people living in cities. And that cities are also waking up to their power of transforming people’s lives, but also the consequences of their actions for the planet.

Chris Williams: I think it’s both a challenge and an opportunity. It’s a challenge because the amount of waste that is produced and the amount of consumption activities that are not environmentally friendly, as well as production, is happening disproportionately in cities. It’s an opportunity because if you can get cities right, you can really tackle a big part of the challenge.

Paul Rand: This is where goal 11 comes in.

Chris Williams: I’m very wedded to sustainable development goal 11, which is cities and communities.

Paul Rand: This goal is focused on developing safe and sustainable cities, which really affects everything else. As Luis explained on his previous Big Brains episode, cities create growth and innovations at exponential rates, which leads into all other goals.

Luis Bettencourt: Cities, in some sense, are environments that are always changing and that change, we often think about infrastructure, but it’s also sort of mobilizing culture about what is important in society and the kind of interactions, pooling of expertise, innovation, business models, all this stuff tends to benefit from urban environments. It tends to happen in larger cities because they’re the places where all these ingredients can come together and be dynamical.

Paul Rand: For instance, one of the main targets of goal 11, increasing access to public transportation, is critical to tap into economies of scale. Currently, only about half of the world’s population lives within walking distance of public transit.

Chris Williams: How can we be smarter about looking at the synergies and integrating this for the purposes of allowing these kind of multiplier effects that Luis is talking about.

Paul Rand: One way the UN is pushing on goal 11 is getting countries to adopt urban policy plans developed in collaboration with all stakeholders.

Chris Williams: I think the evidence of this is that the Secretary General has decided that in order to deal with sustainable urban development, it’s really going to have to be a whole system approach. The entire UN system is going to have to get behind this.

Paul Rand: And to some extent, there has been progress on this. As of March, 2021 156 countries have developed these plans and half are already in the implementation phase.

Chris Williams: And they look to you at Habitat as a facilitator, bringing the different parts of the UN family together so that as they’re able to advance their mandate, whether it’s education.

Paul Rand: Which is goal number four. In 2019, only 59% of children, age three, were proficient in reading.

Chris Williams: Health.

Paul Rand: Goal number three, which has actually seen some good progress. The global mortality rate for children under five was halved, from 2000 to 2019. And this includes mental health. The global suicide rate has declined by 36%.

Chris Williams: Women’s empowerment.

Paul Rand: Goal number five. And this one hasn’t been so great. The global average of women in single or lower chambers of national parliaments was only 25.6% in 2021. At the current rate, it will take no fewer than 40 years to achieve gender parity in national parliaments.

Chris Williams: Regardless of the part of the UN system, there is an urban strategy to achieve that.

Paul Rand: One of the biggest problems of goal 11 is trying to address the proportion of the urban populations who are living in slums, which has reached over a billion people. That means there were three times as many people as the entire US population living in slums. This ties directly into goals, one and two, in poverty and in hunger.

Luis Bettencourt: Its important to say that there has been tremendous progress being made along some of these goals, particularly having to do with reducing poverty, reducing hunger, immense progress in public health.

Paul Rand: Before the COVID pandemic, the share of the world’s workers, living in extreme poverty fell by more than a half from 2010 to 2019.

Luis Bettencourt: All this is translated in a tremendous increases in life expectancy. So there’s a lot of amazing progress that’s been happening. And this is partly also why the population of the world is growing and people can come to cities, is that all this is becoming possible. If you produce environments that work well, that are healthy, that produce good livelihoods, then that also addresses many of the other issues. You just ask, “Okay, end poverty.” Where? It’s about people. So where are people? So, this may mean urban poverty, which may have certain characteristics, but may also mean rural poverty.

Luis Bettencourt: But nevertheless, you have to be looking at settlements, which is what UN Habitat does. And it’s also what we do at the Mansueto Institute, cities of all sizes, small and big, you have to essentially take these challenges of policy and context. And this is also something important, it has to do with the practice of executing them. There are context, appropriate solutions for these sort of large scale aspirational goals. That also then leads to sort of a strategy. When you think about accountability and agency, you start working with local governments, as Chris also emphasized.

Paul Rand: These goals are global, massive even. But part of the UN strategy for accomplishing them is actually for smaller localities to create solutions built from those individual contexts.

Luis Bettencourt: So, the main strategy to do this is quite simple. It usually goes in the name of localizing the goals or localizing sustainable development, right?

Paul Rand: There’s that old saying, you have to eat the elephant in small bites. You’ll fail trying to do it all at once.

Chris Williams: We take for granted that in the United States, the counties let alone the states and cities that have enormous powers in terms of local legislation, independent elections, local revenue generation, et cetera. And they can make a lot of these decisions, whereas in other parts of the world, its very centralized and the decision-making is at central government level.

Luis Bettencourt: But also this is all very much being driven by progress in data and the ability of people to report situations, both data that you got from a satellite and data that can be generated by communities. And so this is really creating something that’s somewhat different from the way we’ve been doing policy, where there can be accountability at different scales, because they’re talking about common objectives, even though they have to be at the same time, learning what are context appropriate solutions.

Paul Rand: As you listen to all of this, it is easy to think about this in some ways as a bit abstract, but it gets a little more real when you talk about where the United States fits, a little bit where some different cities fit. But if you’re a listener of this program and you’re hearing about these SDGs and you think, “Well, where do I fit into this? How do I track it? What role do I play in it?” What do you tell people?

Luis Bettencourt: You can bring these to your life in many different ways. Obviously there are things that we can do in terms of our own actions personally to alleviate poverty or to use energy that’s greener. But this is really a plan for collective action. So it’s something in which of course, we as citizens, can play a role of these of our government, but also this is being internalized by businesses, which increasingly are holds to governance that follows ESG principles, so environment, society, and governance, which are very much aligned to the SDGs. In fact, the SDGs are often the framework for them.

Luis Bettencourt: And of course, local communities in cities, which in many ways, as we discussed before, are the leaders in implementing many of these goals. So as these being internalized, but also made context appropriate and appropriate at different scales, there’s a lot of roles that people can play and implement them in ways that are proper to different societies, with different priorities.

Chris Williams: On a local level, I’m actually quite amazed at the speed with which the issue of climate change has been internalized among people of very different ideological persuasions.

Paul Rand: Combating climate change, goal number 13.

Chris Williams: It’s not just one group of people and it’s now, I think, becoming a concern for businesses. They’re now starting to take this into consideration in their own planning processes. And it’s being addressed quite significantly in the various local councils of cities and local governments across much of the world, as they say to themselves, “Well, how much funding have we been able to allocate for the upcoming extreme weather events?”

Chris Williams: Rom New York City, an extreme after Hurricane Sandy, that they’re looking at a 10 to $15 billion breaker that would minimize the likelihood of another major hurricane. And then there’s a debate about whether that’s where that 15 billion should go. Shouldn’t it be going into other potential adaptation measures or should it more profoundly be looking at radical carbon neutral approach to the city by not 2070, but something closer to 2030, 2035? The fact that different segments of population at the local level have really, I think internalized the issue, suggests that, and are taking actions and making it part of their basic planning processes and thinking and longterm strategic planning, to me indicates that there is scope for optimism.

Paul Rand: One of the things I’m unclear of is and it comes to mind, Chris, as you were talking about some of the hurricane abatement type methods sort of being thought of for use in New York City. But then you start really getting to the point of saying, as these disasters and impacts start happening and really affecting into cities, who makes the choices and where do you make the choices about, do I put $15 billion into New York? Do I say that’s too much as populated as it is? And we got to spread that across, 10 other cities around the world? Where do these decisions of where to invest and where do you say, I’m sorry, this is just not a place we can keep investing in this because just by nature, this is going to be an area that’s going to be not a sustainable place to be.”

Chris Williams: I think the decision maker in terms of where to invest and where not to invest is at multiple levels. With federated societies and countries with a lot of devolved public administration and decision-making, it’s very much at the local level, so that’s an important distinction. Then, regardless of whether it’s centralized or localized, the degree to which there is a popular participation in decision-making, is the planning process inclusive? Are these budget negotiations transparent? Are they open to engagement on the part of the wider population? Can people in general participate in those decisions, and if so, are they able to navigate the political pressures coming from vested interests, whether that’s real estate concerns or businesses or populations that are often significantly affected by this? Do they have some clout in terms of organizing themselves in those decision-making, that have enormous implications on them? That’s all local. AM I optimistic at the global level? Not really. Am I optimistic at the local level? Yes.

Paul Rand: After the break, how Trump’s presidency and COVID-19 have affected progress on the sustainable development goals. If you’re getting a lot out of the important research shared on Big Brains, there’s another University of Chicago podcast network show you should check out, it’s called, Not Another Politics Podcast. Not Another Politics Podcast provides a fresh perspective on the biggest political stories, not through opinions and anecdotes, but through rigorous scholarship, massive data sets and a deep knowledge of theory. If you want to understand the political science behind the political headlines, then listen to, Not Another Politics Podcast, part of the University of Chicago Podcast Network.

Paul Rand: The sustainable development goals were set in 2015 and they’re supposed to be completed by 2030. So the obvious question, given all of this, is how’s it going?

Luis Bettencourt: There are some of the goals that obviously suffered a lot from COVID.

Paul Rand: Estimates show that between 2019 and 2020, we saw the first rise in the extreme poverty rate since 1998. It increased so much, that it undid all the progress made since 2016.

Luis Bettencourt: We know enough to be able to say that goal number four is about education. And so I think anyone listening to this who has kids knows how hard it was to keep kids sort of in school, sort of through the pandemic, and this is probably people certainly like me, could have kids in school through Zoom, but in most parts of the world that was not possible. So there’s a whole generation of people that lost one, two years of schooling at critical ages.

Paul Rand: It’s projected that the pandemic will cause an additional 101 million children to fall below the minimum reading and math proficiency, wiping out all of the educational progress we’ve achieved over the past 20 years.

Luis Bettencourt: The second one is gender equality, right? We are understanding much better that for example, related to kids, but also to livelihoods and the investment in education, we are learning that women were typically affected much worse than men, often to do with childcare, but for other reasons, too.

Paul Rand: On average, women spend about two and a half times as many hours as men doing unpaid domestic work.

Luis Bettencourt: The picture will still become clearer, but it’s obvious that when these crises hit and some of these dimensions of progress get affected differently, and that these too provide us some lessons that we must learn.

Chris Williams: I think the pandemic has done a couple of things. One it’s given us a different view about the public sector and what public goods are and what we sort of take for granted when we’re going through our day-to-day lives. Even my friends that are really down on government and would like small government and noninterference, that they’re really happy that the government was there when there was a crisis. So there’s that recognition. And I think as Luis has catered over this discussion, not just the government, big G, but little G, what’s in your county? People are now looking very closely at what their county executive is saying about the COVID response measures, and they’re taking that quite seriously. Not only because it affects their health and wellbeing, but because they’re a key player. So, there’s this recognition of the state and particularly what the state [inaudible 00:17:18].

Chris Williams: And second is that there’s a recognition that the world is very unequal in your own backyard. Visible aspects of inequality and poverty, I think have been really elevated. And the fact that you have one set of lifestyle, COVID was one thing, but if you had a different lifestyle and you’re really on the front end of service delivery and not able to work from home behind a computer, you experienced COVID in a really different way. So there’s a recognition of inequality.

Chris Williams: The third is that cities, I think were really the epicenter of the pandemic and how cities reacted and responded were quite important. And that I think has led to discussions about how our cities are designed. Do we have a lot of open space, or we don’t? How are our buildings designed? Density is important because it provides access and it’s convenient, but should that border on overcrowding? That’s a huge problem.

Chris Williams: You look at the data in Los Angeles and you move from the coastline, the Pacific Ocean eastward, you’ll see higher incidences of COVID by virtue of the density of not just dense, it was dense throughout, but the overcrowded nature of the housing, often occupied by multiple people. So this is, I think, a deeper thought about how cities are designed. And the last one is really a question about if these local governments are so important and urban spaces are really key to our global health strategy and our safety and security, how are those local governments financed? Do they have the resources necessary to do this?

Paul Rand: And there’s a big question about costs here. The UN Conference on Trade and Development estimates that the annual cost of achieving the UN goals would be 2.5 trillion per year.

Chris Williams: What happened during COVID is actually there was less money coming into the coffers of the city, precisely at the time when the city had to spend more money to help people, we call that the scissor effect. And this was a big problem. So how do we look not just in the US, but globally, at how cities can be better financed.

Paul Rand: The SDGs are global. Every nation in the UN committed to them, but how are we doing in the US?

Luis Bettencourt: Out of the G20, we’re the worst country in terms of making progress towards achieving the sustainable development goals, yes. And the second worst is Russia.

Paul Rand: I’m going to take just a second to reiterate that. The US, the richest country on earth, is doing worse than any other G20 country at meeting these goals.

Luis Bettencourt: So even though this agenda has been signed by the United States, its never been sort of thought as to be mostly, our problem, its mostly the problem, of other nations in the developing world.

Paul Rand: That’s not a proud position to be in for this country, is it?

Chris Williams: No, and I think it’s important to understand that it really does matter who’s in charge in the White House, just, on a factual basis. The sustainable development goals were embraced by the Obama administration all the way up to Valerie Jarrett and above, straight into the White House. And it wasn’t just the State Department and the foreign policy of the United States at that time, was looking at the sustainable development goals as a framework to organize their engagement with the rest of the world. Now, fast forward to the Trump administration and the word sustainability was a word that could not be used in Washington. It was during the G20 negotiations, the Secretary General passionately appealed to member states to agree on a statement. And the US said, “Okay, we’ll agree to agenda 2030, which is another name for sustainable development goals, but we won’t use the word sustainable development goals.”

Paul Rand: And what was our government’s problem with using the word?

Chris Williams: Our government was seeing sustainability as a partisan issue that was associated primarily with climate action, which under that administration was either denied or not something that people wanted to engage in with the administration. And secondly, the United Nations was seen as some kind of evil force in society, not a mechanism to try to bring consensus around the world. So this was a very strident, ideological position that was taken during the Trump administration, that until the very last year of the Trump administration, where it sort of thought a little bit, the logic of supporting the sustainable development goals, really went from extreme, where it was an organizing principle under the Obama administration, to one in which it was not accepted writ large by the Trump administration. The Biden administration has been quite explicit about a commitment to climate action, both in terms of its role in the international community, that will be making a very big push for the COP 26.

Chris Williams: And also, at least as this party is trying to articulate the stimulus package, that’s a big piece of the stimulus package is how to make the infrastructure investments green? How to spur alternative energy to lower the carbon footprint of the country over time? That’s on the green side, but on the social piece, we find an important emphasis on dealing with segments of the population, vulnerable peoples, that have been marginalized historically and making investments both at the global level, as well as the national, towards that aspect. So there’s a full embrace of the sustainable development goals, again.

Paul Rand: As I listen to you both talking, I’m quite struck by the idea of how encouraging and optimistic you both sound and what we are collectively bombarded with on a daily basis, that actually sounds like the last thing we’re doing is making progress on some of the bigger issues that are facing the world. So is it under reported what’s happening? Are you guys being overly optimistic here?

Luis Bettencourt: Yeah, I would say, two things. The first one is that in the face of the crisis ahead, now and ahead, cynicism or pessimism is not an option, right? And doing nothing and reading the news is not a way to make any progress. When we look at these goals, when we look at what’s been happening sort of with a wide lens of looking internationally, and looking at larger numbers and longer periods of time, we’ve made enormous amount of progress in the last decades. It’s undeniable and it’s spectacular, including some of the tools that we’ve learned through COVID to cope with interaction at distance work, public health, vaccines, all kinds of things.

Luis Bettencourt: Now, I think there are many personal and group strategies that we shouldn’t dismiss when we’re positive, but at the same time, we should know that we have the capacity in terms of knowledge, science, research, and in terms of potentially collective action to address these issues. If we’re not doing it, its because we don’t have a consensus politically, and in other ways, and that, because we’re not put the resources to solve these issues. This is connected to many, many things, including how we run our economy, but also just the will and the clarity of vision to address these issues. It’s not like we know everything, but we certainly have a path forward. And the SDGs give us a framework to give us a path forward. So in some sense, we should feel, I always like to quote Madeline Albright, who used to say that she was an optimist who worries a lot. I feel that way too.

Luis Bettencourt: But I think the part about optimism is that we have the capacity actually to solve these issues and to solve them towards a world that’s better for most people and for the environment, but we need to be able to move and learn as we go. This is very much again to bring us back home, what we tried to do at the University of Chicago at Mansueto Institute is really create the multidisciplinary environments, collaborate with UN Habitat and many other organizations and universities, to create the kind of knowledge that the students that will go and be the leaders of the world that’s ahead, will have the tools and the confidence and optimism, but also the clarity of mind to really address these issues as we look ahead, because we need to be fast and we need to know how, and you can only do that if we have good knowledge as well.

Matt Hodapp: Big Brains is a production of the UChicago Podcast Network. If you like what you heard, please give us a review and a rating. The show is hosted by Paul M. Rand and produced by me, Matt Hodapp, thanks for listening.

Episode List

The Urgent Need to Reinvest in American Research, with Barbara Snyder (Ep. 60)

AAU president discusses how more federal funding can secure American innovation

How Alternate Reality Games Are Changing The Real World with Patrick Jagoda and Kristen Schilt (Ep. 59)

UChicago scholars design ARGs to address issues ranging from climate change to public health

What Remains Unanswered After The 2020 Election, with William Howell and Luigi Zingales (Ep. 58)

UChicago economist and political scientist discuss the polls, what lies ahead for Biden and the country post-Trump

When Governments Share Their Secrets—And When They Don't, with Austin Carson (Ep. 57)

Scholar discusses the political theater of foreign policy—and the case for declassifying intelligence

How We Can Fix a Fractured Supreme Court, with Geoffrey Stone (Ep. 56)

Legal scholar examines how nomination of Amy Coney Barrett could tip an increasingly politicized bench

Correcting History: Native Americans Tell Their Own Stories (Ep. 55)

How scholars helped a Chicago museum rethink its representation of Indigenous peoples

The Future of Voting And The 2020 Election, with Assoc. Prof. Anthony Fowler (Ep. 54)

A leading political scholar discusses voting by mail, mobile voting and why he thinks it should be illegal not to vote.

Why The Quantum Internet Could Change Everything, with David Awschalom (Ep. 53)

A world-renowned scientist explores quantum technology and why the future of quantum may be in Chicago

The Way You Talk—And What It Says About You, with Prof. Katherine Kinzler (Ep. 52)

A leading psychologist explains how speech creates and deepens social biases

From LSD to Ecstasy, How Psychedelics Are Altering Therapy, with Prof. Harriet de Wit (Ep. 51)

A leading scientist explains the medical impacts of psychoactive drugs and the popularity of microdosing