Immunotherapy, which unleashes the power of the body’s own immune system to find and destroy cancer cells, has shown promise in treating several types of cancer.

But the disease is notorious for cloaking itself from the immune system, and tumors that are not inflamed and do not elicit a response from the immune system—so-called “cold” tumors—do not respond to immunotherapies.

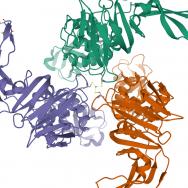

Researchers at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago have taken a step toward solving this problem with an innovative immunotherapy delivery system. The system finds tumors by seeking out and binding to the tumors’ collagen, then uses a protein called IL-12 to inflame the tumor and activate the immune system, thereby activating immunotherapy.

Results from tests in a mouse model are promising: Several types of melanoma and breast cancer tumors either regressed or disappeared altogether in response to the treatment. The results were published April 13 in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“This combination really opens a new approach in cancer immunotherapy,” said leading biomolecular engineer Jeffrey Hubbell, who co-authored the research with Prof. Melody Swartz and postdoctoral scientist Jun Ishihara.

Going from cold to hot

Cancer patients often undergo an array of toxic chemotherapy and radiation treatments. Recently, checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) have offered a new way to treat the disease. These immunotherapy drugs block proteins called checkpoints, which allows the body’s own T cells to find and kill cancer cells.

But tumors must be “hot”—inflamed and therefore able to be found by the immune system — for CPIs to work, making them ineffective in cancers that create cold tumors, including breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers.

Scientists and engineers have known that IL-12, a cytokine that regulates T cell responses, can turn cold tumors into “hot” tumors. But the protein is so powerful that when administered to humans, it can cause system-wide toxicity and death. Scientists have long looked for ways to administer IL-12 directly to tumors without causing side effects in the rest of the body.

Directing IL-12 and immunotherapy at collagen

Last year, Hubbell and his collaborators developed a drug delivery system that attaches therapies to a blood protein that circulates and binds to collagen in areas of vascular injury. Because tumors are filled with leaky blood vessels, the protein sees those vessels as vascular injury and binds to them, delivering the therapy directly to the tumor’s collagen.

Now, the researchers attached IL-12 to the protein and used it with CPI therapies. Once injected intravenously, the protein found the tumor’s collagen, bound to it and released the therapies, turning the cold tumors hot.

In mouse models, most of those with a certain type of aggressive breast cancer saw the cancer disappear after treatment. The researchers also tested the therapy on several types of melanoma, and found that many of the tumors regressed, resulting in prolonged survival.

“These positive results are in tumors where checkpoint inhibitors normally don’t do anything at all,” said Hubbell, who is the Eugene Bell Professor in Tissue Engineering. “We expected this therapy to work well, but just how well it worked was surprising and encouraging.”

Creating a less toxic treatment

Because IL-12 was delivered directly to tumors, it reduced the toxicity levels, making the therapy two-thirds less toxic than before.

Next the researchers plan to continue to study the therapy’s toxicology and continue to work on masking IL-12 from the rest of the body. They ultimately hope to move the therapy to clinical trials.

“Once we have a way to make a cold tumor hot, the possibilities for cancer treatment are endless,” Hubbell said.

Other authors on the paper include graduate students Aslan Mansurov, Peyman Hosseinchi, Lambert Potin, Tiffany M. Marchell, Aaron T. Alpar, Michal M. Raczy and Laura T. Gray; and postdoctoral scientists Ako Ishihara and John-Michael Williford.

—Article first published on Pritzker Molecular Engineering website.