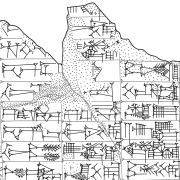

“The Moon that fell from heaven”—a story first inscribed on clay tablets in the 14th century BCE—begins with a celestial accident: the Moon tumbles to earth and encounters the workings of nature.

In a new translation by Ph.D. student Naomi Harris, the Stormgod sends rain upon the Moon, to their mutual surprise and anguish. Thanks to Harris’s attentive choices, this ancient Hittite poem, alongside two others, has found new life in The Paris Review.

As made possible by Harris, who is pursuing a joint degree in Middle Eastern studies and comparative literature, the publication marks an extraordinary crossing of worlds. An ancient Anatolian hymn now appears in a poetry magazine known for debuting some of the most acclaimed writers of the past 75 years, such as Adrienne Rich and Italo Calvino.

What may be The Paris Review’s oldest dated poems are reborn through Harris’s translation—where Hittite rhythm and divine drama are carried over into English for modern ears. Readers can also hear Harris’s recitation on the magazine’s Instagram, the language’s first widely sounded utterance in some 3,000 years.

How does a long-extinct language become newly legible to contemporary imagination?

That question lies at the heart of Harris’s research. Her translations explore how beauty survives in fragments, and how poetry mediates between the broken and the living. Each of the three poems she translated—“Telipinu went” (1450–1350 BCE); “They sent an ox” (late-fourteenth-century BCE); and “The Moon that fell from heaven” (1350–1190 BCE)—contemplates departure and renewal.

Gods, animals, and nature mourn and transform; in their grief and wonder, Harris finds the outlines of a shared human inheritance.

Harris’s approach unites scholarship, philology and creative writing—an integration nurtured throughout her years in the Arts & Humanities Division. Drawn to a place where ancient languages still flourish, Harris chose UChicago for its rare instruction in Hittite and for the wide range of languages taught across the University.

After finishing her AB in English literature and AM in Middle Eastern studies, Harris entered the Ph.D. program to conduct research spanning Middle Eastern and comparative literature. Faculty encouraged her to treat translation as an analytical, historical and creative mode of inquiry.

“My professors have absolutely shaped the work I do,” Harris said. “They’ve encouraged me to use poetry as another way of accessing these ancient texts and contextualizing them in the present.”

Now a frequent teaching assistant for “Anatolian Thought and Literature”—a College Core course that introduces students to film adaptations, paintings, short stories and plays—Harris continues to watch students discover how alive ancient voices still sound.

As taught by Theo van den Hout, professor of Hittite and Anatolian languages, the class invites students to engage ancient texts through creative projects. Students even baked bread from centuries-old recipes they reconstructed.

“I found it so incredible because seeing all these different adaptations and interpretations brought to life different aspects that I hadn't noticed before,” Harris said, reflecting on the course, “and we need these different perspectives to help us imagine the forever-inaccessible historical whole.”

For Harris, translation is inseparable from interpretation.

“Translation, like scholarship, is an interpretive process,” she explained. “You have to decide what aspect of a word or a sentence to convey. For example, the Hittite waštul can mean sin, offense, transgression or simply missing the mark.”

The spaces between the meanings of waštul represent a moral and poetic ambiguity that gives the poems a modern feel.

Her path to these translations began in “Exploratory Translation,” a graduate course co-taught by Haun Saussy, University professor in East Asian languages and civilizations and the Committee on Social Thought, and Jennifer Scappettone, associate professor of English.

The class prompted students to test the limits of fidelity.

“We practiced all kinds of translation strategies,” Harris said. “It made me appreciate the different ways Hittite texts could be brought into modern languages.”

This blend of intellectual and artistic freedom is made possible because of UChicago’s commitment to ancient and less commonly taught languages. The community Harris found among fellow Hittitologists—anchored in philology, cultural history and linguistic study—has been essential.

“Nothing compares,” she said, “to spending hours each week with others who’ve read the same text and come up with different interpretations.”

The university’s collaborative ecosystems of comparative literature, near Eastern languages and civilizations, and creative writing converge in Harris’s work, enabling scholarship that bridges worlds. During her qualifying exams, she even composed an original poem and analysis in place of a traditional essay—a choice her advisors supported.

When English Prof. Chicu Reddy, a member of The Paris Review’s editorial board, read her translations, he urged her to submit—and later, to resubmit.

“When we at the magazine first looked at Naomi’s translations of Hittite poetry, it felt like something entirely new to us—mostly because it was incredibly old,” said Reddy. “Like Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red or Alice Oswald’s Memorial, Naomi’s translations make the ancients new to me.”

The board and Harris discussed at length how to present the verse to contemporary readers, whether as translations, adaptations, or something in between.

“We asked ourselves all kinds of fundamental questions about poetry, authorship and translation,” said Reddy. “Our sense of literature’s horizon was expanded in the process.”

Now, Harris’s translations grant these ancient texts an afterlife far beyond the academy.

“Creating a translation that works as a poem in English means giving these voices a new audience,” she said.

Read Harris’s translations and “Making of a Poem: Naomi Harris on ‘Telipinu went’” in The Paris Review.

—Adapted from an article originally published on the Arts & Humanities Division website.