For much of American history, the books that children read have largely centered on white, male characters—but is that starting to change? Not very much, and not very quickly, suggests new research from the University of Chicago.

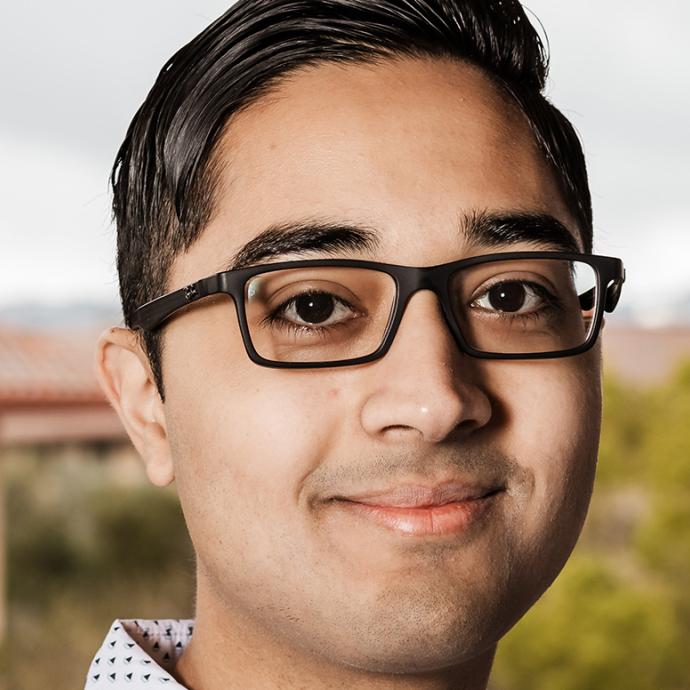

In a new working paper, Asst. Prof. Anjali Adukia of the Harris School of Public Policy found that over the past 100 years, characters in children’s books—as measured by images and text—are largely white and male. This white/male dominance is even true of books published in recent decades, which have seen heightened awareness about race and gender issues.

In fact, Adukia and her co-authors—Emileigh Harrison, Teodora Szasz and Hakizumwami Birali Runesha of the University of Chicago, and Alex Eble of Teachers College, Columbia University—found that mainstream children’s books have grown less representative in terms of skin color of characters pictured over the last two decades. Surprisingly, children themselves are underrepresented in children’s books as well.

“These findings have important implications for educators and publishers, and others concerned about the influence of books on childhood development,” said Adukia, whose research focuses on educational inequalities. “Research has demonstrated that the way that people are represented within books can contribute to children’s understanding about what roles they and others can or cannot inhabit.”

So how do children’s books stack up in terms of issues pertaining to race and gender?

To answer this question, the authors developed new artificial intelligence tools to analyze images in books, building on advances in the field of computer vision. They trained AI models to detect faces, classify skin color, and predict the race, gender and age of the faces. The effort analyzed 1,133 children’s books totaling more than 160,000 pages that were likely to appear in homes, classrooms and school libraries over the last century.

The works were categorized as either: “mainstream books,” those selected without explicit intention to highlight an identity group; and “diversity books,” which did explicitly highlight an identity group. They found that children were twice as likely to check out mainstream books from a major public library system relative to other books, suggesting greater exposure to the messages in these books.

“We find that mainstream books, which children are more likely to encounter, are more likely to depict characters with lighter skin than ‘diversity books,’ which are specifically selected to highlight people of color or females,” Adukia said. “Perhaps most surprising was that children are portrayed with lighter skin than adults in each collection, which has concerning implications for how perceptions related to youth and innocence may be shaped.”

In short, mainstream children’s books have gotten whiter in recent years. The authors’ analysis of images revealed the following about race in children’s books:

- Books in the mainstream collection are more likely to depict lighter-skinned characters than those in the diversity collection, perhaps speaking to the assumptions of book publishers about the assumed preferences of the median reader.

- Also, while female characters have always appeared in pictures over time (still less than 50% on average, but closer to 50% than in text), they are predominantly white.

- Particularly surprising is that despite no systematic differences in skin tones across ages in society, children are more likely than adults to be shown with lighter skin, regardless of collection.

The authors also compared the incidence of female appearances in images to female mentions in text to find that:

- Female characters are more consistently visualized (seen) in images than spoken about (heard) in the text, except in the collection of books specifically selected to highlight women and girls. This suggests that many books symbolically include female characters in pictures without substantive inclusion in the actual story.

- This underrepresentation holds regardless of the measure used: predicted gender of the pictured character, pronoun counts, specific gendered words, famous figure gender, and character first names.

Males, especially white males, are persistently more likely to be represented by every measure, with little change over time despite substantial changes in female societal participation.

Even though these books are targeted to children, adults are depicted more often than children in both images and text.

“The process of education itself—and its associated books and curricular materials—necessarily, and by design, transmits not only the values of society, but also whose space it is. The inclusion and exclusion of different identities send messages which can contribute to how children view their own potential and the potential of others which can then, in turn, shape subconscious defaults,” Adukia said. “Understanding what identities are being presented to children through their everyday books is a needed step in order to be able to make informed decisions about what content to include in curricula and to help mitigate the structural inequality that pervades society and our daily lives.“

The authors anticipate that their innovative application of AI will lead to further development of tools that can measure how people are represented in books and other media, and thereby help determine what content depicts characters in their full humanity. In addition, their methodology offers the promise of further inquiry into other forms of text and visual media, including literature and nonfiction, journalism, websites, art, photography, television, videos, movies and many others.

—Versions of this story were previously published by the Becker Friedman Institute and the Harris School of Public Policy.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He