Show Notes

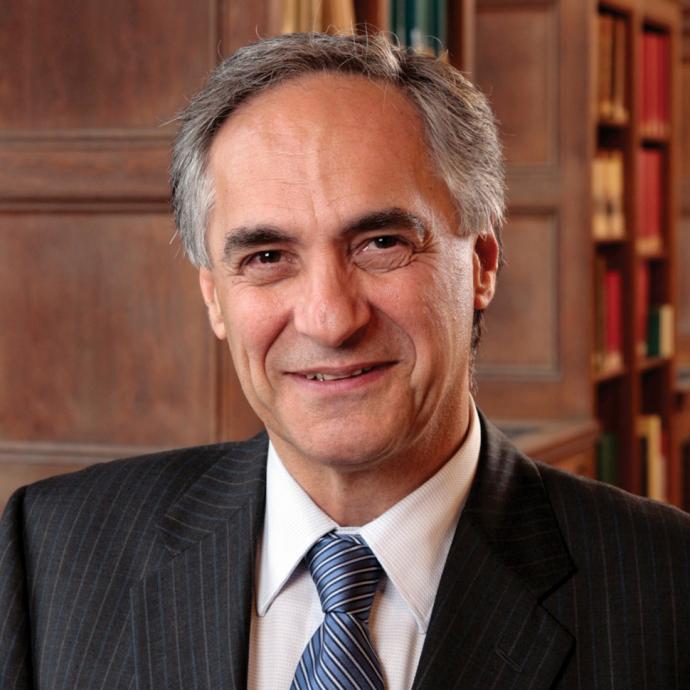

As president of the University of Chicago, Robert J. Zimmer has a unique view on the future of higher education, and one of the biggest obstacles he sees is access for all students.

“Is the country going to invest in the future of young people, or is it not? And is it going to provide access to higher education for people from all sorts of financial backgrounds? I think this is so important to the future of the country,” said Zimmer, who discussed UChicago’s commitment to expanding college access.

On this episode of Big Brains, Zimmer describes free expression on college campuses; his efforts to expand the sciences, arts and humanities; and developments for UChicago around the world, including a new center in Hong Kong.

Subscribe to Big Brains on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher and Spotify, and rate and review the podcast.

Related content:

- America’s Best University President—New York Times

- The Free-Speech University—Wall Street Journal

- Why the University of Chicago Opposes ‘Trigger Warnings’—Wall Street Journal

- $100 million initiative enhances UChicago’s commitment to lower-income students

Transcript

NARRATOR: From the University of Chicago, this is Big Brains with Paul M. Rand, conversations with pioneering thinkers that will change the way you see the world.

RAND: Robert Zimmer is a mathematician, a champion for freedom of expression and the president of the University of Chicago. He’s been described by a New York Times columnist as America’s best university president. And I was thrilled when he agreed to join me on Big Brains.

RAND: In our wide-ranging conversation, we discussed some of the challenges and opportunities facing higher education, as well as the unique vision he has brought to the University of Chicago as president and what future developments he’s most excited about. Enjoy our discussion. And don’t forget to rate and review Big Brains on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to the show.

RAND: Well, President Zimmer, we are thrilled to have you as a guest on Big Brains today. Thanks for joining us.

ZIMMER: It’s a great pleasure.

RAND: You have a view—It’s a pretty rare view—into higher education in your role here. And if you started looking forward, where do you see us going over the next five years, 10 years, not only as an institution, but, I think, in terms of the industry as a whole?

ZIMMER: Well, I think it’s going to be—I mean, there are two questions here. One question is, where would I like it to go? And the other question is, where do I see it going? Is the country going to invest in the future of young people, or is it not? And is it going to provide access to higher education, to a good higher education, for people from all sorts of financial backgrounds?

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: And this is, I think, is so important to the future of the country. And it’s important on a human level so that people are actually fulfilling their potential. But it’s important on a societal level.

RAND: Absolutely.

ZIMMER: We are, from a national point of view, we’re in a competitive environment. Competition’s a good thing, so it doesn’t bother me that we’re in a competitive environment. On the other hand, you want to do well in a competitive environment. And for the country, succeeding in building and evolving the higher education system so that people are genuinely able to enter it is exceedingly important.

ZIMMER: This has to be done through public institutions. Seventy-five percent of the students in higher education are in public institution. This cannot be done exclusively in private institutions. So this is a very important thing. And now you ask, do I see it happening? Not necessarily.

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: I can’t say that I’m seeing signs that give me great optimism that there’s going to be this realization and turnaround.

RAND: And investment.

ZIMMER: Nationally. And investment. The good news is that there are institutions, and quite a number of them, that are working very hard to be accessible to a broader array of students and to continue to provide the kind of transformative experiences for individuals. But there are fundamental challenges to that right now. And one is the nature of support for public higher education.

RAND: Support as in financial support.

ZIMMER: The financial support for public institutions in this country, public institutions of higher education, has been decreasing dramatically for years.

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: State legislatures are simply not committed to public higher education as a public good at the level that they had been. And I think that reflects the fact that the citizenry has some different perspectives, different priorities.

RAND: Is that kind of at the root of what you think are kind of perpetuating some of the challenges facing higher education today?

ZIMMER: That is definitely perpetuating some of the challenge facing higher education. The question of access and student debt are very serious problems.

RAND: OK. Let’s break those down. When you say access, what does that mean?

ZIMMER: It means, do you have a student who can actually afford to go get a college education? And is that going to be a good education that comports with what it is that they’re looking for and the aspirations they can have? And there are too many situations now where students without financial resources are having a challenging time finding that type of education without taking on large amounts of debt. And this is a fundamental national problem. So that, I would say—

RAND: And it doesn’t seem to be getting any better, does it?

ZIMMER: No. It’s not getting any better. Now one of the ironies is that when you look at what are thought of as elite higher education institutions—like the University of Chicago, like the Ivies, like the other great and well-known liberal arts colleges—these institutions have been investing extremely heavily in financial aid so that the access to these institutions is now, from a financial point of view, much, much easier than it used to be. And in fact, I would argue that, at this point, anyone who gets in, certainly a domestic student who gets in, can afford to go to many of these institutions without any debt and can afford to go to almost all of these elite institutions with limited debt.

RAND: And the University of Chicago is doing its part to ease those financial burdens. Can you please talk about something called the Odyssey Scholarship Program?

ZIMMER: Our efforts here were greatly stimulated by a $100 million anonymous gift that launched the Odyssey Program. This gift really captured the University community and concept in an extremely important way. It was a statement of extraordinary values by an anonymous individual. But it so resonated with the University community that literally thousands and thousands of alumni, and even people who were not alumni of the University, have contributed to this to make this a more robust program.

RAND: Can you explain a little bit about how the program works?

ZIMMER: Yes. So the original goal of the program was students from the lowest family income brackets could graduate without debt. I mean, this was a hugely important step for us. And gradually, over the years, we expanded this in many ways, realizing that that was one major obstruction to students from these families being willing to come to the University of Chicago, were thinking they were able to come or thinking they should even bother applying.

ZIMMER: But there were many others. There were other sorts of barriers. So we systematically looked through, what are the set of things that are places where students from lower income were not able to take advantage of University of Chicago education on an equal footing? We tried going through these one by one, eliminating them.

ZIMMER: So we started with this Odyssey Program, and we enhanced it and built into it what we were calling No Barriers, which was an extension of the Odyssey Program. And this has continued to evolve in multiple ways. And why I feel so good about this program is on the merits and what it is able to do is extremely important and needs to be seen as reflecting the University’s fundamental values.

ZIMMER: But the other reason I feel so good about it is how it’s galvanized the whole University community, the whole University alumni community, so that everybody saw this as of value. Everybody wanted to pay back. And it’s just been a wonderful thing to watch that community galvanize around this.

ZIMMER: And just to capture one thing, one just simple anecdote, I had a parent that, on the day students and parents were coming to campus, I had one parent just ask to talk to me quietly. I said, of course. This was a father, described his family situation. They were both working, didn’t have a lot of resources. And he said to me, “I never imagined that my child would have the opportunity to come to the University of Chicago because of the financial obligation.” And the Odyssey Program has made it happen.

[ADVERTISEMENT]

RAND: You’ve also spoken pretty extensively about the importance of immigration on higher education.

ZIMMER: It’s obviously been a huge driver for many things within the country. And I think when you look at the success of American higher education as being, for many years and continuing today, as the higher education system in the world that is viewed as the strongest, in spite of all the difficulties I’ve been talking about, when you look at that and ask why that is and why the research has been so powerful and effective and why the environment has generally been quite open, it is impossible to look at that question and not see just how important immigration has been to the research environment in this country.

RAND: And to this University in particular.

ZIMMER: To this University absolutely in particular. One of the interesting things is to look, for example, at Nobel Prizes.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: And you see that, if you look at the science Nobel Prizes—so this is in medicine, physics, and chemistry—it’s close to 40 percent of the Americans winning the Nobel Prize have been won by people who were born outside the United States. Now that’s a very particular metric. But almost all metrics you look at show the same thing. The research enterprise has been hugely enhanced by the ability of the United States to be an open, welcoming environment for the most talented people.

ZIMMER: So if you’re really asking how would higher education in the United States have fared, how would the University of Chicago have fared had there not been this openness to immigration, the answer is clearly a lot worse. We would be not nearly as strong and vibrant intellectually.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: Aside from attracting the most talented people into the country, there’s another reason it’s important right now, which is just for the simple experience of all the students and the nature of the environment. Having an environment in a higher educational institution at this point where you have, to take an extreme case, all domestic students is going to give students a very limited view of what the world is like. And you want to train people to be able to engage in and solve complex problems.

ZIMMER: And that can mean societal problems. It can mean business problems. It can mean academic problems, artistic problems, whatever problems. These are going to demand a type of capacity for engaging with people from around the world. And if you haven’t had that experience, your education will simply be limited. So I think, both in terms of pulling in people from around the world who are the most talented from around the world being a positive on its own, the whole sense of defining an environment in which people from around the world are interacting is good for everybody and is critical for domestic students—in the United States.

RAND: Makes great sense.

RAND: So that question, then, on the access, it has a different impact here at the University of Chicago. It’s access of getting in. But it also is fundamental in terms of diversity of views and opinions.

ZIMMER: Yes. So the other issue goes back to, what is the nature of the education we’re giving? Are we providing students with an environment in which they are going to be capable of addressing the complex challenges that they’re going to face when they’re in the workplace?

ZIMMER: Because the challenges are complex. They don’t come in nice, simple packages. And you need to be able to think about complexity and understand power and limitations of argument and what works in some cases and what works in others. In other words, you need to actually be able to think. And I think it’s also starting to be discussed in high schools, which I think is absolutely critical.

RAND: And you’ve put a lot of energy, an increasing amount of energy, looking at high schools.

ZIMMER: I have. I think the question around high schools is extremely important and is actually extremely interesting. Because colleges, of course, every year, take in huge numbers of students. And they’re coming out of high schools.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: So the nature of their expectations of what it means to come to college has been informed by their experience at high schools. And I’ve been spending a lot of time talking to high school leaders about this very question. So one cannot view high schools as if they’re identical to colleges any more than you can view middle schools that are identical to high school.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: Or primary school is identical to high school. So one needs to acknowledge that high schools need to be thought about in a different way. But the question that high schools need to think through is, are they preparing students to enter an environment of intellectual challenge, free expression, and open discourse when they get to college? If the answer to that is no, it becomes that much harder for colleges to take that position—

RAND: To make the difference up, right.

ZIMMER: To make the difference up. And so having that kind of preparation, where students don’t have to pretend they were in college, but are being prepared by their high schools in a thoughtful and purposeful way for entering that world of intellectual challenge and free expression and open discourse, that is an important test for high schools, as far as I’m concerned. And that’s what I’ve been talking to a lot of high school leaders about. And I would say we have very strong set of beliefs and very strong set of experiences demonstrating why this type of education involving intellectual challenge is so critical.

RAND: And this has been core to the University almost since its founding, if not since its founding. Is that right?

ZIMMER: It has. So it’s very interesting to go back and read some of the statements, even in the minutes of faculty meetings from the 1890s. And you see this very, very strong thread of this being intrinsic to the University from its start. And again, you go back and look at Robert Maynard Hutchins, who was a complex character, a complex president. But he had to deal with a number of issues related to the Communist Party, inviting people, and so on.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: And this was not an easy time. And he stood extremely firm around the importance of free expression for being a university. And this was true with Edward Levi. It was true for Hanna Gray. And so when I talk—

RAND: And it’s been true for Robert Zimmer.

ZIMMER: It has been. But I am following a line here of what the University of Chicago’s meant, not just what my own personal beliefs are.

[ADVERTISEMENT]

RAND: Let’s go back to 1977. Is that when you first came here to the University?

ZIMMER: It is.

RAND: How did you get here?

ZIMMER: I had been a graduate student at Harvard. I finished my PhD in 1975. I spent two years teaching at the Naval Academy in Annapolis and then came here as an instructor in mathematics.

RAND: OK. And is this where you came up with the Zimmer conjecture?

ZIMMER: This was a little bit later in the sense that in ‘79, ‘80, I had developed some work that led me to think about the nature of the relationship of symmetry groups to geometry and topology. I will tell you I spent five years of my life never going to sleep without thinking about this problem.

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: I was totally obsessed with it. Ruined my sleep for many years. And sometimes I said I became president of the University so I could get a good night’s sleep. It was work done by a number of mathematicians from different perspectives for a number of years during the ‘80s and ‘90s. And people were stuck. And then just a couple of years ago, there was a huge breakthrough by a former PhD student of mine and two junior faculty members here at Chicago.

RAND: And then your career advanced from there to where?

ZIMMER: I became chairman of Mathematics Department eventually. And then when Geof Stone was provost, he asked me to join him in the Provost’s Office, which I did. And then along the way, I also became Vice President for Research and for Argonne National Lab. Then I went to Brown as Provost for four years and then came back as president in 2006.

RAND: So what went through your mind at this time of saying, I have a chance to come back? What was intriguing to you about that? What did you have in mind when you decided to accept that role?

ZIMMER: Well, there were two things. So first, I loved the University of Chicago.

RAND: Why is that?

ZIMMER: Well, there were two reasons. First, the values of the University of Chicago and the feeling of what it feels like to be here was extraordinary. And you, as a faculty member, you have this sense of being part of a whole and being part of a university that has meaning. And it has a purpose. And it believes and has a culture of commitment to intellectual challenge and rigor that is just a wonderful environment to work in if it suits you.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: And it suited me.

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: So I loved it for that reason. And the second reason I loved it, it has been a place that fostered me from the time that I was a junior faculty member and a great place for me to work and a great place that had supported me in many ways. And so it was both this kind of higher view of what a university meant and what it felt like and what it had done for me.

ZIMMER: On the other hand, I had been involved in University administration here. I had seen the University from a high level, being in the Provost’s Office and being vice president. And I had a sense that there was a lot that the University could do to fulfill the kind of values that it had in new ways and in more ambitious ways.

RAND: OK. So you came into the role with a pretty healthy dose of ambition. And if you had to boil down, say what you really came in thinking you wanted to grow and develop and nurture, where were you going to place your bets?

ZIMMER: There were places where I would say the University had gotten too complacent about the way it thought about things and that it needed to imagine itself as having greater capability, greater ambition, and a greater sense of potential for impact. And I take impact here in multiple ways, whether it’s scholarly, educational, impact on society, and so on.

ZIMMER: A big issue, of course, was the question of having a university that had no engineering at the time. And we were not, and we should not, just start to say, well, what are good engineering programs? Let’s be like that. That’s sort of a loser approach, frankly. But the question was, given our particular institution, our particular strengths, where is it that we can make a particular and singular contribution? And that led to the Institute for Molecular Engineering, which has just been absolutely—

RAND: Growing gangbusters.

ZIMMER: It’s a wonderful success and already deeply connected to many parts of the University—

RAND: Very much.

ZIMMER: In an extremely productive way.

RAND: There’s some pretty strong energy around that these days.

ZIMMER: There is. And I think the whole question around quantum information is a totally fascinating one, because it is something that both connects to understanding fundamental issues about science and then how you connect that to the potential for managing and collecting information in a totally different way. And Argonne, Fermilab and the University are now formed what we’re calling The Quantum Triangle.

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: Because the capacity and interest that all three of them bring to this whole area of quantum information is complementary in many ways.

RAND: Big things to come from this area.

ZIMMER: Big things to come, absolutely.

ZIMMER: Another area which has gotten a really healthy amount of attention during your tenure has been the arts. And I wonder if you can talk about where that interest comes from and some of the things that you’ve particularly focused on.

ZIMMER: Yeah. So let me answer that by making the question slightly broader and talk about the arts and the humanities, because I feel that the way we need to look at this is as a deeply interconnected way. I’m somebody who believes very deeply in the importance of the humanities as a piece of education. This has been something that the University has always believed in. It’s been critical to the nature of the Core. And it’s been critical to the way we’ve talked about and thought about our education. And I think it is problematic that some institutions around the country are withdrawing from this.

ZIMMER: And why this is so important—and I’ll connect this to the arts in a second—is if you do not have a concept of the importance of culture, the importance of context, the importance of history on the way individuals are acting, thinking, responding to their societal environment, the way societies are organized, the way these history and culture shapes and has an impact on political decision-making, on economic decision-making, if you do not have this, you are missing a huge amount of the complexity that goes into understanding the world.

ZIMMER: Now the arts are deeply connected to this in that, if you really ask about what they’re about at some high level, it’s about the expression of meaning. And that then becomes not only a creative act, but it becomes an act of communication around these very issues. And I think what—so that simply from a point of view of having a rich enough environment for what it means to be delivering an education at the highest level, having the humanities and the arts deeply involved in the university is very important.

ZIMMER: Now what we focused on over the last several years regarding the arts was not just the question of analyzing the arts, but of bringing in a much greater emphasis on performance and production of the arts to go along with what had been what I would say is a great tradition in art history and musicology.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: This connects to our community on the South Side. It connects to the city. It connects to the number of artists who come through Chicago from around the world. So we’re in a natural environment where the nature of artistic production and performance can be an extremely vibrant part of our campus environment. And that’s one of the things we’ve been very happy pursuing.

RAND: And we’re just celebrating, what, the five-year anniversary last year of the Logan?

ZIMMER: Five-year anniversary of the Logan Center, which has been, I think, transformative in terms of the capacity of our students to be themselves, to be actively engaged.

RAND: Very much.

ZIMMER: And we’re opening the Green Line Performing Arts Center in Washington Park. And this been something, honestly, I’ve wanted to see happen for 12 years. There are a lot of very small theater groups, other artistic groups—though I will confess, I was focused on theater groups—that they’re small. They’re a little bit startup. They’re sometimes community-based. They’re not big enough or financially secure enough to have their own space. Sometimes what they do is magical. Sometimes what they do is not magical. But the magic is—but getting the magic is absolutely worth it.

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: And so having this space, part of the concept behind the space was providing, in a rotating way, space for these theater companies that can produce magic and will produce magic, but that are not able to afford their own space. So I’m very excited about the opening of that, which is coming soon.

RAND: How does being in an urban setting affect how we operate, what we study, how we look at the world?

ZIMMER: The urban environment is, I would say, very important to the nature of the types of work that’s been done at the university for many years and the type of impact that the University has had. A lot of the challenges and opportunities that the country faces and that individuals face are captured in cities. Obviously, not all of them—rural environment’s also critical and has its own types of qualities, which are equally as important. But with the increased urbanization of the country, and the world, in fact, understanding cities and what’s happening in them becomes increasingly important.

ZIMMER: And cities are both a source of tremendous energy, economic development, personal growth, creativity, entrepreneurship. But they’re also environments in which many people end up being left behind. So how do you think about these challenges? How do you address them? And how do you understand, take advantage of the opportunities? So the University, for many years, has been a leader in the type of research into urban issues, both how do you understand them? How do you help governments? How do you help NGOs? How do you help individuals?

RAND: Right.

ZIMMER: And this has been going on for over a century. It continues to go on. And of course, being situated in a city makes it a very natural venue for that type of work to take place.

RAND: OK. So from our immediate surroundings, we also have some things that are happening around the world, including, you’re going to be headed to Hong Kong in late November.

ZIMMER: I am.

RAND: What’s going on there?

ZIMMER: Yes. So when I first came back to the University as president, at the very first meeting I had with the board, I raised the question with them, among of a bunch of questions I was raising, what about China?

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: How do we think about it? And what about India? How do we think about India? So you have two countries together that capture a huge portion of the world’s population. Particularly China, of course, is evolving at an extraordinary pace. And the political, social, economic, and cultural evolution there is dramatic and having huge impact on the world. So the question was, what do we do about that? And how does the University think about what our connection to China should be?

ZIMMER: So we thought about this quite a bit, had a lot of discussions with a lot of faculty. And we opened the center in Beijing. And the goal there was for our faculty and our students from across the University to be able to go to China, work with Chinese colleagues on various sorts of projects. That was the agenda of the faculty member.

ZIMMER: We were not saying, here’s our agenda. Who wants to fit into it? We were saying, our agenda is to support you in your work if you are interested in going to China, working with Chinese colleagues, and understanding some issue of substance. We’re going to China became an important thing.

ZIMMER: So that was very successful. And then with that, one other thing happened, which was that the Booth School Executive MBA Program, which had been in Singapore, decided they wanted to move to Hong Kong.

RAND: OK.

ZIMMER: And the combination of moving to Hong Kong and the activity at the Beijing Center, we decided we were going to actually build a center in Hong Kong, which was a bigger scale than any of the centers that we had around the world.

RAND: That’s actually now a campus. Is that right?

ZIMMER: It’s now a campus that has been built. The opening will be in November. And that’s why I’m going. And it’s going to be a beautiful building on a beautiful site overlooking the water. We’ve received great support for it from our alum and trustee, Francis Yuen. And this will be Francis and Rose Yuen Campus. And also great support from the Hong Kong Jockey Club. And we will have the Hong Kong Jockey Club University of Chicago Academic Complex there. So it’s going to be a very exciting moment.

RAND: President Zimmer, it’s been a wonderful conversation. And I’m excited to see what comes next in your tenure. Thanks so much for joining me on Big Brains.

ANNOUNCER: Big Brains is a production of the UChicago Podcast Network. To learn more, visit us at news.uchicago.edu and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play and wherever else you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening.

Episode List

SCOTUS Nears Unimaginable Era with Geoffrey Stone (Ep. 8)

Legal scholar Geoffrey Stone discusses why we are on the verge of an unimaginable era for the Supreme Court, the forgotten history of Roe v. Wade and free expression on college campuses.

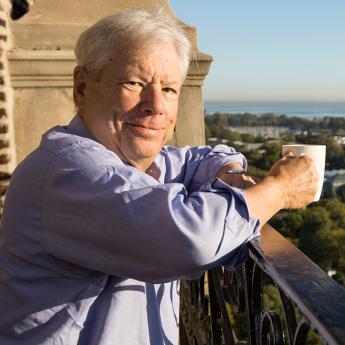

Economist’s Journey to the Nobel with Richard Thaler (Ep. 7)

Richard Thaler discusses how a bowl of cashews inspired his early research, how he missed a 4 a.m. Nobel wakeup call from Sweden, and what it was like to act in a movie alongside Selena Gomez.

Future of Energy Innovation with Michael Polsky (Ep. 6)

In this alumni edition of Big Brains, Michael Polsky discusses his early days in the energy field, his current project to build one of the largest wind farms in the world and why he believes in the power of innovation.

The Expanding Universe with Wendy Freedman (Ep. 5)

Prof. Wendy Freedman discusses her research on measuring the age of the universe, her leadership of the Giant Magellan Telescope and the search for life outside our solar system.

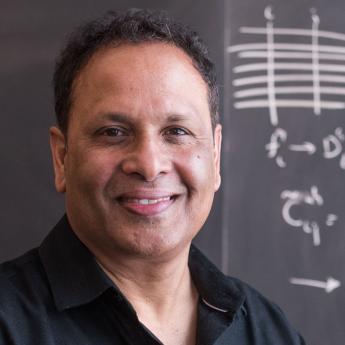

Nature’s Design Secrets with Rama Ranganathan (Ep. 4)

Prof. Rama Ranganathan shares his pioneering research on evolutionary physics, and explains why he believes biology is at a similar point today as engineering was two centuries ago during the Industrial Revolution.

Mind of a Virtuoso Composer with Augusta Read Thomas (Ep. 3)

Prof. Augusta Read Thomas gives a glimpse into the creative process of a world-class composer, discusses the state of classical music today and how she helps train the next generation of composers.

Myths of U.S. Health Care with Katherine Baicker (Ep. 2)

Prof. Katherine Baicker discusses research on the true costs and benefits of expanding health care, dispelling a number of myths, and provides insights into how to improve health care for all.

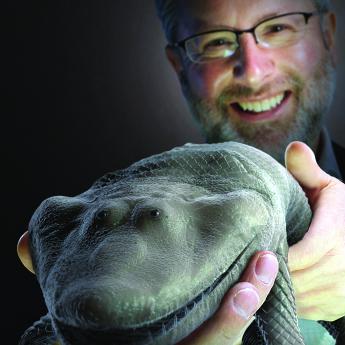

Discovering the Missing Link with Neil Shubin (Ep. 1)

Prof. Neil Shubin discusses his discovery of Tiktaalik roseae, the 375-million-year-old fossil that was a missing link between sea and land animals—and what it meant for the understanding of human evolution and how it has impacted the future of genetic research.