Improv, short for improvisational theater, is a live performance in which the actors make up scenes, dialogue and characters on the spot (sometimes incorporating suggestions from the audience). It’s often comedic, though not always.

Inspired by earlier theater forms like commedia dell’arte and cabaret, modern improv began at the University of Chicago in the 1950s. A group of UChicago students, alumni and friends used theater games developed by educator Viola Spolin to create something that had never existed before—an improvisational theater.

From their revolutionary storefront grew famed improv theaters like The Second City and iO (formerly ImprovOlympic), which have produced household names like Stephen Colbert, Steve Carrell, Amy Pohler and Tina Fey.

What is improv?

Improv is a form of unscripted performance. Instead of relying on prewritten dialog, or even the sets and props of traditional theater, improvisers create scenes based on loose scenarios. Everything from what the performers say to the faces they make to how they move their bodies is entirely made up on the spot.

Improvised scenes often incorporate suggestions from the audience. For example, a performer may ask the audience to provide a location for the scene (say, a hospital, or a jelly bean factory) or an occupation for one of the characters (a phlebotomist, a lion tamer, etc).

When improvisers use these prompts within scenes or games lasting a few minutes, it’s called “short-form” improv. In “long-form” improv, performers develop a lengthier scene, similar to a short play, based on a single premise.

Today, in almost every major city in America, you can find a troupe of improv performers taking the stage each night. Improv is the foundation for Saturday Night Live and Whose Line Is It Anyway?. Its techniques and games have permeated classrooms, even corporate retreats and doctors’ offices.

Is improv different from sketch comedy?

The terms “sketch” and “improv” are often used together. However, in sketch comedy, scenes are almost always short; they can be entirely prewritten or use a combination of improvised and prewritten elements. Saturday Night Live is a sketch comedy show, though its writers and performers (often trained improvisers) occasionally use improv to develop written sketches.

If you’re going to catch a comedy show at The Second City in Chicago or Upright Citizen’s Brigade in New York or Los Angeles, you’ll likely see a combination of both sketch and improv.

When was improv invented?

Improvised performances have existed in some form for centuries, but modern improv largely evolved in the late 1950s at the University of Chicago. The artform’s inventors drew inspiration from older forms of theater, like commedia dell’arte, and also incorporated theater games developed by educator Viola Spolin.

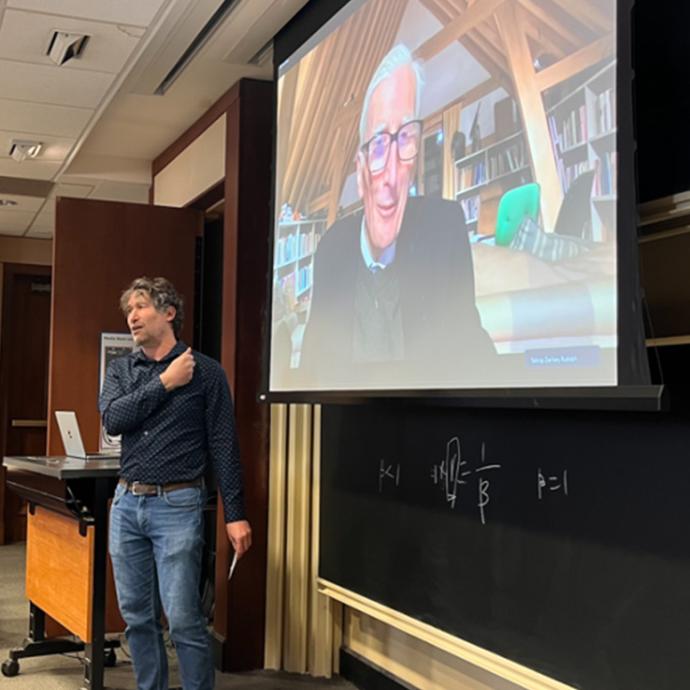

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He