What were some of the more memorable assignments or projects the class undertook?

Scott: I made a board game with a few of my classmates. It’s a Game-of-Life-style piece based on Fermi’s Paradox. You progress through these twisting disasters and collect technology resources to become a space-faring civilization. We’ve also got different trivia questions so that people can get tokens while learning about some of the concepts we’ve covered in class.

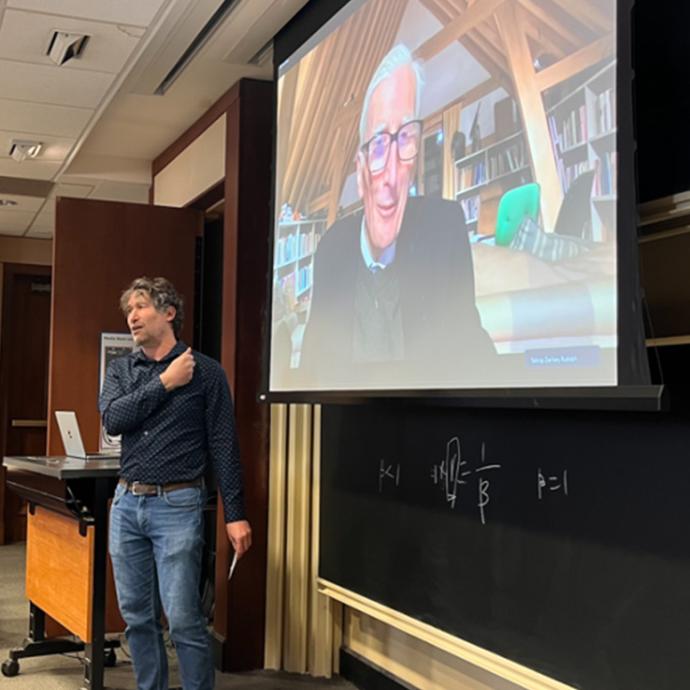

Holz: [The projects] from the 2021 class captured a wide range of people’s reactions and creativity. There was one which was a version of the children’s book “Goodnight, Moon,” titled “Goodnight Moon, Adapted for Doom.” Some students did an architectural portfolio for doomsday bunkers. We’re excited to see what the students come up with this year!

How should we deal with the grief of doomsday, and how did you approach that concept in this course?

Holz: It is dark, and you don’t want to let that overwhelm you because it doesn’t lead to action. We’re all part of humanity, and if we engage, we can make a difference. At the end of the day, no one wants to see our home planet become uninhabitable. That’s in no one’s interest. The more you can focus on that, the better.

Scott: That’s the hardest thing about being intellectually invested in these kinds of scenarios because I think grief is the wrong emotion. If you have these stages [of grief], denial isn’t helpful—we’ve covered that—but the anger and the bargaining piece? I think that is. I don’t think we should ever complete the grief process, because that is the nail in the coffin of this whole debacle, and I don’t want that.

Is ignorance bliss, regarding doomsday?

Holz: There are times in the class when you’d just rather not know. It would be so much easier to go work on black holes—that’s such a fascinating topic and it’s such an exciting time in the field. On the other hand, this is the world we live in. Something is gratifying about learning these things and trying to think about solutions. That’s why we’re here, in a community like UChicago. We want to learn. We want to understand how the world works, so that’s what we’re doing.

Scott: If you can’t see a future, then I don’t know if you’re ever going to have productive action, because you need to have a vision that you want to realize. Action is more important than ignorance.

What’s the scariest doomsday scenario, in your opinion?

Scott: I think what I see as the most pressing reality is the nuclear situation. As we have these continuously escalating global conflicts, almost every other thing you discuss boils down to nuclear. It’s like the illusion of free choice—it’s all nuclear in the end.

Holz: A full nuclear war would be beyond awful. Climate change is happening right now, and it’s only going to get worse for another 20 years, given all the projections. So that’s also terrible, and it makes nuclear war more likely. But right now, the fear of the day is disinformation, since it impacts our ability to address all of the existential threats. If we can't agree on basic facts, rational discourse is compromised, and society can no longer address its greatest challenges.

Are we truly doomed?

Scott: The best answer is that we don’t have to be. Seeing other people take these questions seriously makes me feel not alone, and makes me think there is a future we can all build together. Whether we are the ones who ultimately become people in positions of power—or maybe we’re able to have an impact on those who are—[having these conversations] is what can turn the tide.

Holz: To be completely honest, my answer varies. There are some topics where you come away feeling more hopeful and others where you don’t. I hope we’re not doomed. We’re a lot less doomed if, for example, students engage and carry this with them going forward. And that, for sure, is a good thing.

—This story was originally published on the University of Chicago College website.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He