Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories spotlighting how faculty, students and alumni at the Harris School of Public Policy are driving impact for the next generation. Leading up to the May 3 grand opening of the Harris’s new home at the Keller Center, these stories will examine three of the most critical issues facing our world: strengthening democracy, fighting poverty and inequality, and confronting the global energy challenge.

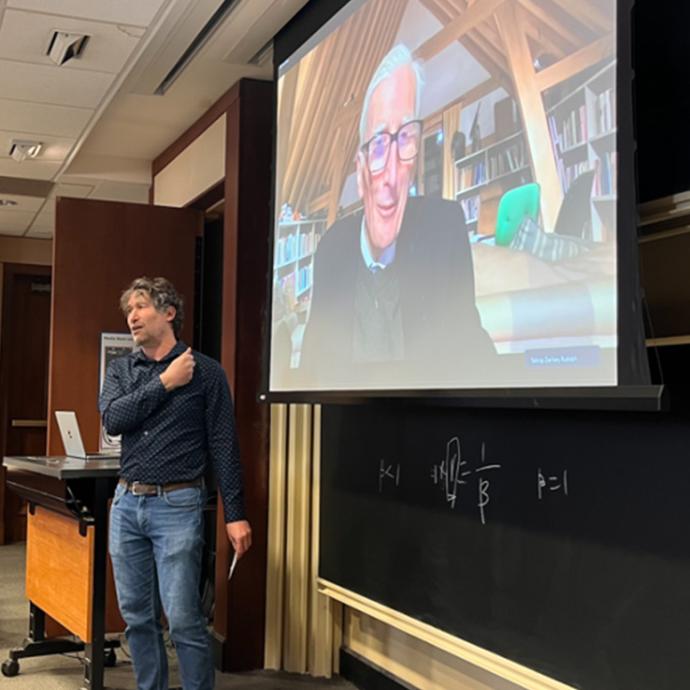

Prof. William Howell sees serious threats to democracy in the United States.

Howell, a leading scholar on American political institutions, recently sat down with the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy to discuss how the United States got here and ways to strengthen democracy here and abroad. The scholarship of Howell, the Sydney Stein Professor in American Politics, focuses on separation-of-powers issues and American political institutions, especially the presidency. He teaches a popular course at the University on the presidency.

What’s is the state of our democracy today?

In short, it’s not good. Trust in government and political institutions is remarkably low, and the quality of public debate about pressing issues is at once vacuous and polarized. The capacity of our political institutions to solve problems is not what we need it to be.

We have a president and a Republican party willing to launch—either by themselves or through their proxies—attacks on the legitimacy of the courts, the press and civil servants. It’s an intentional and well-orchestrated attempt to cultivate deep distrust in the federal government.

The work of democratic stewardship is not just one of preservation. It’s one of continued investment and renewal. As a country, we are failing on both accounts.

What are the factors that contribute to growing government distrust?

There is not one single source of distrust. Some is born of fabrication, lying and demagoguery. Some is formed by our institutions’ seeming inability to function properly. And some, by real disagreements regarding whose interests should be served by the government. The wealthy? The poor? The middle class?

These questions are also fueled by larger demographic changes that contribute to significant social unrest and anxiety. We have seen this particularly among white men who are accustomed to privilege and power, which they see as being threatened. So there is no one origin point for distrust, but rather a convergence of factors. When you combine distrust with hyper-polarization—among classes and races—you end up with a pretty toxic mix.

What are the implications of this distrust?

At very basic levels of governance, public distrust proves corrosive. In order for bureaucracy to function, agencies require regular funding and the opportunity to plan over the immediate and long-term. Public distrust threatens both. With rising public distrust, members of Congress are less willing to allocate funding, and when they do grant financial support, they subject agencies to additional oversight. Meanwhile, the public is less prone to support and cooperate with the administrative state. With rising public distrust we see heightened demand for lower tax rates and greater resistance to tax collection efforts. This lack of trust between the state and the public damages every aspect of government—from basic functionality to a long-term erosion of morale and efficacy.

You’ve written about and discussed the legitimization of bigotry. How does this legitimization influence today’s politics?

It clearly is having an influence. The willingness of this president to put up with—and deliberately stoke—blatant bigotry and racism doesn’t just legitimize these positions, but emboldens them. White nationalists see an ally in the White House. This is extremely consequential in terms of their posture and influence. They are normalized and accepted as—if not conventional—then as a justified and credible part of society. We have entered an era where bigotry and racism are unapologetically out in the open.

This situation is exacerbated by rising inequality in America. As the divides between rich and poor become more and more acute—often crossing racial lines—there is an earnest need for serious work to be focused on pragmatic, lasting solutions. But as long as a populist occupies the White House, there is no chance for meaningful attention to this. Trump is more focused on exploiting these divides for his own gain, using the bully pulpit to marshal public support of his own private, largely anti-democratic agenda.

How does the presidency of Donald Trump factor into the challenges to democracy?

Even if President Trump were not in the White House, these threats to democracy would still exist. There are an undeniable set of systemic forces that allowed President Trump to capture one of our two major parties. And when Trump leaves the political realm, as he someday will, these larger threats will linger.

Indeed, the stage is set for someone even more dangerous to come into the White House.

Is this just a U.S. challenge?

We are witnessing a rise in populism globally—and it’s not an accident that we are seeing it rise in so many places at the same time. In Europe massive flows of immigration touched off tremendous anxieties about the capacities of states to meet emergent challenges. We are witnessing disruptions associated with automation and globalization that institutions around the globe have struggled to attend to. There are profound challenges that governments around the world are facing. How will they deal with structural changes to their economies? To a warming climate? To rising inequality and corruption and insecurity? Should states fail to attend to these challenges, publics eventually will demand governing alternatives.

In many ways, you paint a pessimistic picture of the state of democracy. What can be done?

The times require something akin to a second progressive movement, where wide segments of the public seek reform to allow for and encourage richer and more meaningful debate. I’m working on a new book with Terry Moe from Stanford exploring how this movement might take shape. It would attend to the problems of tone and language in our discourse, and also to the design of our political and policy institutions to more effectively solve problems. If we don’t undertake this work, I fear, we will remain vulnerable to the kinds of public appeals that President Trump—and future President Trumps—will make.

—This story first appeared on the Harris School of Public Policy website.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He