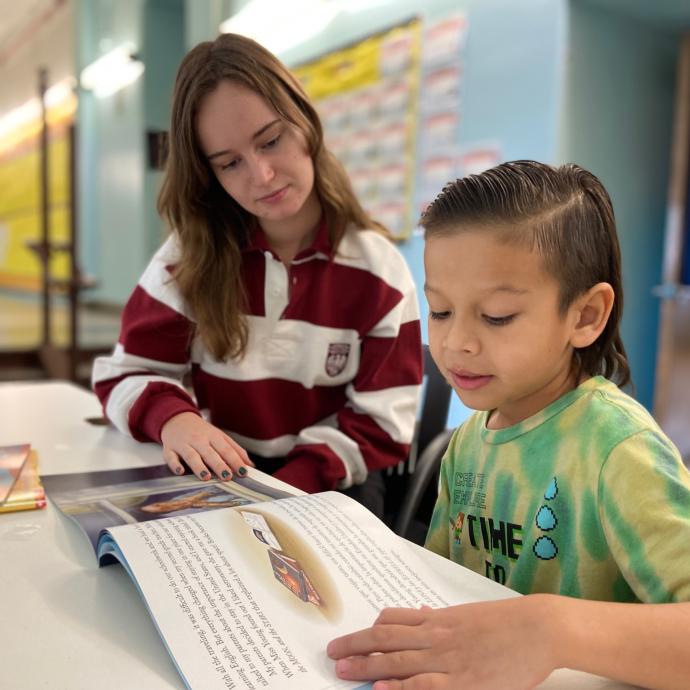

Phoebe Han, a first-year student planning to double major in economics and psychology, wanted to emulate Vicuña’s technique of interviewing strangers. She ventured out into the city, stopping passersby in Chinatown and Greektown.

Kassi, who plans to major in computer science, took a different approach. When watching the film, she wished Vicuña had sat longer with each person and asked more follow-up questions. She sought out creative people she knew: her R.A. and a close friend. Those in-depth conversations connected her to others.

Both students got a range of responses, though noted that many people brought up rhythm and music. Kassi chatted at length with one interviewee about the musician Mitski—a conversation that prompted her to think about the artist in a new way.

“We don't often have the time to think about our experiences and really ruminate on them for our own benefit,” she said. “But with poets and musical artists, especially Mitski, they force us to sit down and think about these connections that we might not fully realize.”

Both Han and Kassi took “Poetry and the Human” because of experiences with poetry in high school, but felt like the course shifted their understanding of both the practice and interpretation of the art form.

“I developed more skills in terms of close reading, but hearing my classmates' perspectives on poetry, and seeing just how different interpretations of the same text can be, was what I got most from the class,” Han said.

“It wasn't until I took this course that I understood that, yes, there can be different interpretations of a poem,” Kassi said. “That's the point!”

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He