Afrofuturism is a blending of many genres, beliefs and histories. The artistic aesthetic and critical framework brings in “elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magic realism with non-Western beliefs,” writes Chicago author Ytasha L. Womack in Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture.

It would stand to reason that a course on the topic would also be a medley—pulling in literature, music and other art forms.

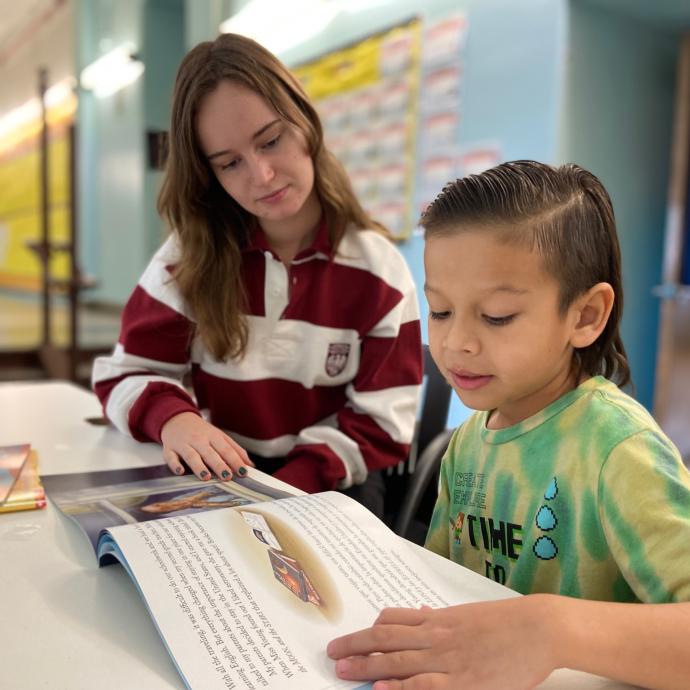

Taught by UChicago Assoc. Prof. Eve L. Ewing, “Afrofuturism(s)” took the blending of elements one step further: The undergraduates in the class explored the topic alongside students from the greater Chicago community.

“What makes this course so radical—to me—is the way it challenges every aspect of my educational experience,” one student wrote in an anonymous evaluation. “More than ever, it feels like education is becoming siloed and very individualistic…This class said: What does learning look like when we invite our community to be a part of the learning process?

“It means deeper and richer conversations in which life experiences are taken to be as important and valuable as theoretical arguments or academic lexicon.”

A community approach

Afrofuturism has been a core theme Ewing’s work for many years. Ewing, an associate professor in UChicago’s Department of Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity (RDI), underscores the city of Chicago’s particularly rich influence on Afrofuturism—including poet and artist Krista Franklin and musician Sun Ra.

In deciding to teach a course on the topic, Ewing noted that Afrofuturism is an area where there remains a lot of debate about what it is and what it is not.

—Prof. Chuan He

—Prof. Chuan He